Introduction

In its effort to restore itself into a global power center and secure dominance in the post-Soviet area, the concept of the “near abroad” or the exclusive sphere of influence found a broad recognition in Russian political and economic elites long before the Putin regime, at the very beginning of its rule, played with the idea of friendly relationships with the West.[1]

The concept of the “energy empire,” originally developed by Anatoly Chubais, matured over time into a well-functioning model, in which the trade with gas and oil acquired not only economic but also political importance and allowed Moscow to exert influence in recipient countries, capitalize on it, and penetrate other sectors of national economy.[2] Multiple studies conducted in Europe proved that increased political influence had been directly linked to the phenomenon of initial “positive economic cooperation” turning into a source of negative and malign power.[3] Georgia, a country experiencing turbulent democratic transformation, is still far from having stable and resilient democratic institutions, capable of continuing political development and functional stability despite disruptive external interference. Thus, it is of high importance to study and reveal the economic foundations of Russian political influence and its general patterns that, as demonstrated in many cases, presumes dominance in key sectors of the national economy, through which it becomes possible to infiltrate, ‘infect’ and weaken political institutions, ultimately enabling Kremlin to exert significant influence (state capture) over the national political decision making (making it more pro-Russian). In the end, the targeted political institutions and the system itself become Russian-like, characterized by oligarchic rule and decline of democratic culture. Not to forget that Georgia, a country that energetically aspired for EU and NATO membership, is repeatedly confronted with the need to increase its institutional resilience, with the EU placing specific emphasis on economic diversification and energy sectors, and NATO highlighting the need for partner countries to improve resilient institutions capable of thwarting external pressure and coercion.[4]

This study aims to fully understand the complexity of the Russian economic footprint in Georgia and its distribution among major economic sectors. Key economic players (enterprises) in each sector will be identified and tested to their political and economic dependence on Russia, which, once aggregated in sectors, will render a broader picture of Russia’s economic influence (footprint) in each sector and the national economy in general. Further, the major variables of Russian economic influence will be subject of correlational analysis with the strength of democratic institutions, in an attempt to establish the evidence of interdependence patterns (more influence leading to the decline of democratic institutions).

Analytical Model and Methodology

The application of means of economic expansion for political purposes is a well-established feature of Russian foreign policy. Since there is little distinction between the state-controlled and private businesses, often intertwined in Russia, large-scale direct investments abroad bear a high likelihood of the state political interest lurking behind. In addition to establishing the picture of the Russian footprint in a number of economic sectors via shares in turnovers, GDP, export, and direct investments, we will take a deeper look into the nature and sources of financial capital, structure, and form of business ownership in each relevant sector. Due to the small size of the Georgian economy, some sectors experience a strong monopolization tendency, allowing few companies to dominate entire sectors, dictate “rules of behavior,” and therefore directly or indirectly exert influence over politicians associated with the business activities in those sectors.

Consequently, the degree of importance of each sector for the national economy will be accessed via indexes, based on its share in the national GDP, employment, foreign direct investments (FDI), and export. Additionally, we include in the analysis economic fields such as Energy and Communication & Transport, regarded as critically important due to their strategic relevance for Georgia, not the least from a security perspective. Once the aggregated sectoral index is established, the threshold of 4 % will indicate whether the particular sector deserves further investigation. Sectors above 4 %-index constitute nearly 80 % of the national economy, whereas eight sectors placed below 4 % have only the marginal effect of 2.3 %. Therefore, only in sectors that rank 4 % and above, major companies will be shortlisted and categorized in two groups: Category-1 and Category-2. Companies with an annual income above 100 mln GEL and asset value over 50 mln GEL belong to the first category, and those companies with income from 20 to 100 mln Gel and asset value from 10 to 50 mln GEL are included in the second category. Next, companies from both categories had been color-coded into black (heavy Russian influence), red (partial risk of Russian influence), and green (free of Russian influence), in accordance with the degree of Russian political or financial influence assessed on the basis of a set of indicators such as Russian citizenship of the (co)owner, availability and transparency of business information, source of financial capital, offshore registration, etc. The share of ‘black’ and ‘red’ companies in each sector made it possible to assess the approximate scale of the Russian footprint, subsequently generating the entire picture of Russian economic influence on the macroeconomic level, i.e., the national economy. Finally, a regression model had been introduced, with the possibility to track the interdependence of the economic variables of Russian influence (such as export, direct investments, and money transfers) with the strength of the domestic (in Georgia) democratic institutions, evaluated on the basis of Freedom House and World Bank indicators.

Major Sectors of the Georgian Economy

Identifying major sectors allows us to analyze the national economy from a macroeconomic perspective and spot the true size and emphasis of Russian influence in the Georgian economy.[5] From the list of 14 economic sectors, those exceeding 4% share of the national GDP will be selected first and adding sectors’ shares in national employment, FDI, and Export, an aggregated sectoral index will be created, allowing for a much more nuanced (relevance dependent) ranking of most critical sectors.

The aggregated index calculation applies the same 4 % threshold for the sectors under consideration and is based on 2003-2018 data. The results are not surprising, with Manufacturing, Transportation, Trade, and Construction as the top sectors in every regard. Accordingly, the next step of the study aims at measuring Russian footprint in the top sectors of the national economy and Russia’s contribution to major economic indicators such as FDI, Export, and Visitors as major drivers and indicators for growing (or declining) Russian economic influence.

Table 1: Sectoral Shares and the Aggregated Index.

Sectoral Share in GDP | % | Sectoral Share in Export | % | Sectoral Share in FDI | % | Aggregated Index | % |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 19.4 | Manufacturing | 43.8 | Transportation | 23.2 | Manufacturing | 19.3 |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 11.8 | Wholesale and retail trade | 28.7 | Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 13.0 | Mining and quarrying | 3.0 |

| Manufacturing | 11.6 | Transportation | 12.7 | Manufacturing | 11.6 | Trade | 17.2 |

| Transportation | 9.4 | Mining and quarrying | 6.1 | Financial and insurance activities | 11.2 | Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 14.2 |

| Construction | 9.1 |

| Construction | 9.6 | Transportation and communication | 13.7 | |

| Health and social work activities | 6.7 |

| Real estate activities | 9.2 | Construction | 6.2 | |

| Real estate activities | 6.3 |

| Hotels and Restaurants | 6.9 | Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 4.9 | |

| Education | 5.5 |

|

| Financial and insurance activities | 4.1 | ||

| Other service activities | 5.0 |

|

|

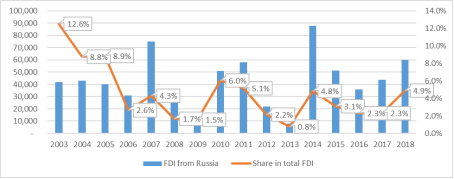

Seemingly, the Russian FDI follows the general behavioral pattern of the total FDI (variability), although from 2014 on, it shows a general growth tendency (Figure 1). It must be noted that investments originating from offshore companies constitute a considerable share of the total FDI, and hence it is not possible to identify the original source. With high probability, Russian investors actively use offshore activities to move financial capitals to Georgia, thus bringing the real size of Russian investment to a much higher point.Foreign Direct Investments

This section takes a closer look at several macroeconomic indicators through which the dynamics and channeling of Russian economic activities in Georgia become visible. These include the size and structure (sectoral recipients) of Russian direct investments. Additionally, the nature and dynamics of the Georgian export to Russia, as well as the number of Russian visitors in Georgia will be reviewed to assess the degree of Georgia’s sectoral vulnerability against shocks coming from Russia (for instance, a politically motivated embargo).

Russian Footprint in the Georgian Economy

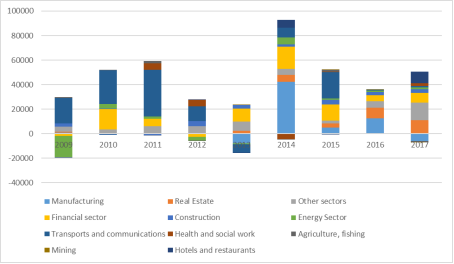

The sectoral distribution of Russian investments is shown in Figure 2, with Finances (27 %), Manufacturing (17 %), Transportation & Communication (8 %), and Real Estate/Construction (8 %) mostly affected.

Figure 1: Russian Share in the Total FDI in Georgia.

Figure 2: Sectoral Distribution of Russian FDI in Georgia (in 1000 USD).

Once again, it must be highlighted that due to the widespread practice of investments made by offshore companies, the share of sectoral distribution of real Russian investments can render a quite different picture. As for the average sectoral distribution of Russian FDI in the period between 2009-2017, Figure 3 shows a similar tendency of the biggest chunk of the pie taken by Transport & Communications (T&C), Financial sector, Manufacturing, and Real Estate.

Figure 3: Average Share in FDI (2009-2017).

Exports to Russia

As clearly visible from the export to Russia dynamics (Figure 4), Georgia again is reaching the point where export volumes hit their records (15 %) similar to 2006, when Russia, driven by political motives, banned Georgian products and imposed a total embargo. The possibility of similar drastic action with respective shocking consequences for the Georgian economy should not be dismissed at all.

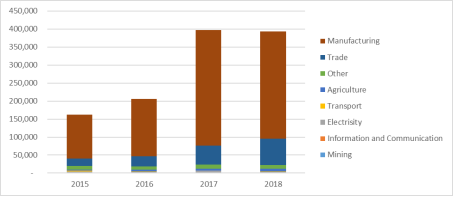

There are a handful of sectors that dominate Georgian export to Russia, and Manufacturing (48 % growth) and Agriculture had experienced exceptional growth rates taking the lion’s share in overall export, as provided by statistics of export sectoral distribution in Figure 5.

Visitors from Russia – Tourism

The growing dependence of the Georgian economy, and in particular tourism, from Russian visitors is clearly visible from the steady growth of visitors from 8.1 % (share of the total) in 2011 to 19.5 % in 2018.

Given the high susceptibility of Russian tourism to Kremlin’s political preferences, i.e., a touristic boycott of the targeted country, Georgia is definitely approaching a point after which Russia’s punitive measures would have serious negative implications on the Georgian economy. Travel restrictions imposed after the so-called “Gavrilov Night” in June 2019 hit the touristic sector heavily and

Figure 4: Export to Russia (Thousand USD).

Figure 5: Export to Russia by Sector (2015-2018, 1000 USD).

Figure 6: International Visitors (incl. from Russia).

once again proved the standard wisdom of not trusting Russia while opening up for economic cooperation.

In conclusion, we can confirm that key macroeconomic indicators for the Georgian economy, such as FDI, Export, and Tourism, show a steadily growing economic dependence on Russia. Formally traceable Russian financial capital flows go primarily into T&C, financial, and manufacturing sectors of the Georgian economy. This is rather alarming, as T&C is officially recognized as strategically important. The financial sector so far enjoyed an incomparably high degree of “freedom of action” compared to the dire conditions of the Russian financial sector, directly dependent on Kremlin’s political goodwill. Although the share of Georgian export to Russia in overall export volumes reached the level of 2006, the absolute number and volume of goods exported to Russia by far exceed those in 2006. Therefore, the risk of repetitive use of economic sanctions for a political purpose has become even greater, with a much higher probability of political pressure and fear of negative socio-economic effects in Georgia.

Analysis of Major Sector Related Companies

Clearly, an article’s limited scope will not allow to encompass all active enterprises in Georgia and conduct an intensive, in-depth analysis to reveal the financial sources, existing control, and thickly entangled mechanisms of influence in each sector. Rather, a more limited yet valid approach has been selected by identifying major Category-1 and Category-2 companies in each economic sector.[6]

Those belonging to Category-1 had to meet the following criteria: annual income over 100 mln GEL and asset value exceeding 50 mln GEL. Category-2 includes all companies with income from 20 to 100 mln Gel and asset value from 10 to 50 mln GEL. Smaller enterprises were excluded from the scope of analysis, despite their considerable number, since the focus on companies in dominant positions in the respective economic sectors. Thus, the study may generate an objectively limited picture of the Russian ‘footprint’ in major companies of the most relevant sectors of the national economy; yet, to a high degree, the results can be generalized and considered valid for the remaining companies, i.e., the entire sector. Second, companies from both categories were color-coded into black (heavy Russian influence), red (risk of or partial Russian influence) and green (free of Russian influence) based on a set of indicators for the degree of Russian political or financial influence, including Russian citizenship of the (co)owner, availability and transparency of business information, source of financial capital, offshore registration, etc. Ultimately, the purpose of this section is to calculate in percentage points the share of Russian-dominated (black and red) companies in major economic sectors, i.e., the Russian footprint in the national economy.

Companies in 2017

The total number of companies in both categories is 397, 85 in Category-1, and 312 in Category-2, respectively. Concerning the turnover of the entire national economy, companies of both categories reach a turnover share of 37 %. Considering that we did not include smaller companies (categories 3 and 4) in our analysis, the real turnover of the “Russian influenced” companies should be related not merely to the mentioned 37 %, but to a much higher percentage. Out of 397 companies, 110 (28 %) are either ‘black’ or ‘red.’ This is a quite alarming number indicating that nearly one-third of the major enterprises in Georgia, that is to a various degree under the Russian influence, make 9.2 % of the national business turnover and heavily dominate mining (63.4 %), energy (36.6 %), and agricultural (24.7 %) sectors (see Table 2).

Table 2. Black and Red Companies in National Economy 2017.

| Sectors: Red and Black | Number | Income, 2017, 000 | Turnover of the Sector 2017, 000 | Share |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 40 | 3,402,388 | 32,816,300 | 10.4 % |

| Energy (power, gas, steam and air) | 10 | 1,077,826 | 2,943,600 | 36.6 % |

| Manufacturing | 21 | 764,329 | 8,532,100 | 9.0 % |

| Mining and quarrying | 2 | 425,717 | 671,400 | 63.4 % |

| Transportation and storage | 11 | 244,178 | 4,699,500 | 5.2 % |

| Information and communications | 6 | 240,913 | 1,657,700 | 14.5 % |

| Construction | 7 | 219,768 | 7,051,200 | 3.1 % |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 5 | 105,192 | 425,900 | 24.7 % |

| Real estate activities | 8 | 101,187 | 1,090,900 | 9.3 % |

| Total | 110 | 6,581,498 | 71,740,300 | 9.2 % |

Fifty-one out of 397 (13 %) ‘black’ companies in Categories 1 and 2 make 4.7 % of the total business turnover, heavily dominate mining (63.4 %) and energy sectors (27.7 %), and have a substantial footprint in transport and construction (Table 3).

Table 3. Black Companies in National Economy 2017.

| Sectors: Black | Number | Income 2017, 000 | Turnover of the sector 2017, 000 | Share |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 16 | 1,331,814 | 32,816,300 | 4.1 % |

| Energy (power, gas, steam and air) | 7 | 815,995 | 2,943,600 | 27.7 % |

| Manufacturing | 13 | 438,095 | 8,532,100 | 5.1 % |

| Mining and quarrying | 2 | 425,717 | 671,400 | 63.4 % |

| Transportation and storage | 6 | 240,913 | 1,657,700 | 14.5 % |

| Information and communication | 3 | 61,844 | 7,051,200 | 0.9 % |

| Construction | 2 | 58,196 | 425,900 | 13.7 % |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 2 | 24,863 | 1,090,900 | 2.3 % |

| Real estate activities | 4,699,500 | 0.0 % | ||

| Total | 51 | 3,397,436 | 71,740,300 | 4.7 % |

Companies in 2018

In 2018 a total of 414 companies belonged to either Category-1 or Category-2, illustrating a growth rate of 4 % as compared to 2017. They provided 34.2 % of the total business turnover (a decline of 2.8 %). Black and red companies (114 in total) make 8.6 % of the national business turnover, which is comparable to the data of 2017, though with a slight decrease (Table 4). The black companies (55 in total) make 4.5 % of total business turnover and dominate mining, energy, transportation, and construction sectors (Table 5).

Within the period from 2017 to 2018, a total of 415 companies had been extensively reviewed, of which 55 were coded as black (fully Russian dominated) and 59 as red (at risk or partially influenced), which makes 27.5 % of all companies in the Categories 1 and 2 (Table 6).

The number of red or black companies has grown from 110 in 2017 to 114 in 2018. Due to the lack of information on turnover for 34 large companies from this list in 2018, we assume the same level of turnover on average as in 2017, and thus their share in the total turnover remains around 9 % (Table 7).

Table 4. Black and Red Companies in the National Economy, 2018.

| Sectors: Red and Black | Number | Income 2018, 000 | Turnover of the Sector 2018, 000 | Share |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 42 | 4,052,831 | 37,409,500 | 10.8 % |

| Energy (power, gas, steam and air) | 10 | 1,087,385 | 3,294,600 | 33.0 % |

| Manufacturing | 22 | 858,090 | 9,212,300 | 9.3 % |

| Mining and quarrying | 3 | 453,276 | 7,171,300 | 6.3 % |

| Transportation and storage | 7 | 318,786 | 5,054,000 | 6.3 % |

| Information and communication | 11 | 222,291 | 749,300 | 29.7 % |

| Construction | 6 | 214,555 | 1,275,300 | 16.8 % |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 8 | 132,136 | 446,900 | 29.6 % |

| Real estate activities | 5 | 107,873 | 1,750,800 | 6.2 % |

| Total | 114 | 7,447,225 | 86,625,200 | 8.6 % |

Table 5. Black Companies in the National Economy 2018.

| Sectors: Black | Number | Income, 000 | Turnover, 000 | Share |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 18 | 1,702,435 | 37,409,500 | 4.6 % |

| Energy (power, gas, steam and air) | 7 | 879,467 | 3,294,600 | 26.7 % |

| Manufacturing | 14 | 491,109 | 9,212,300 | 5.3 % |

| Mining and quarrying | 3 | 453,276 | 749,300 | 60.5 % |

| Transportation and storage | 6 | 214,555 | 1,750,800 | 12.3 % |

| Information and communication | 3 | 79,879 | 7,171,300 | 1.1 % |

| Construction | 2 | 61,441 | 446,900 | 13.7 % |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 2 | 51,169 | 1,275,300 | 4.0 % |

| Real estate activities | 5,054,000 | 0.0 % | ||

| Total | 55 | 3,933,331 | 86,625,200 | 4.5% |

Table 6. Companies Reviewed and Color-coded.

| Sector | Green | Red | Black | Total |

| Real estate activities | 13 | 6 | 2 | 21 |

| Transportation and storage | 22 | 11 | 33 | |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Mining and quarrying | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 125 | 24 | 18 | 167 |

| Construction | 55 | 4 | 3 | 62 |

| Information and communication | 7 | 6 | 13 | |

| Energy (power, gas, steam, and air) | 14 | 3 | 7 | 24 |

| Manufacturing | 60 | 8 | 14 | 82 |

| Total | 301 | 59 | 55 | 415 |

Table 7. Year on Year Change of the Turnover of Red and Black Companies.

| Sectors: Red and Black | Number 2017 | Number 2018 | Change | Share 2017 | Share 2018 | Change |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 40 | 42 | 2 | 10.4 % | 10.8 % | 0.5 % |

| Energy (power, gas, steam and air) | 10 | 10 | 0 | 36.6 % | 33.0 % | -3.6 % |

| Manufacturing | 21 | 22 | 1 | 9.0 % | 9.3 % | 0.4 % |

| Mining and quarrying | 2 | 11 | 9 | 63.4 % | 29.7 % | -33.7 % |

| Transportation and storage | 11 | 7 | -4 | 5.2 % | 6.3 % | 1.1 % |

| Information and communication | 6 | 5 | -1 | 14.5 % | 6.2 % | -8.4 % |

| Construction | 7 | 3 | -4 | 3.1 % | 6.3 % | 3.2 % |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 5 | 8 | 3 | 24.7 % | 29.6 % | 4.9 % |

| Real estate activities | 8 | 6 | -2 | 9.3 % | 16.8 % | 7.5 % |

| Total | 110 | 114 | 4 | 9.2 % | 8.6 % | -0.6 % |

Among the top 100 companies exporting to Russia, 23 companies in 2017 belong to category 1 or 2. Out of these 23, nine are black (7) or red (2), i.e., 39 %, and represent the manufacturing (bottling) sector of the economy exclusively.

The manufacturing industry itself belongs to the risky sector, due to the 22 companies color-coded black and red, making nearly 9 % of the total turnover in the sector;

The wholesale trade sector harbored 42 black and red companies with a share of the respective total turnover of 10.4 % (3.4 bn GEL) in 2017;

Although only five black and red companies were identified in the agricultural sector (2017), their share in the sectoral turnover was 24.7 %;

The energy sector, a strategic sector in Georgia, exhibited ten companies coded in black or red, making 36.6 % (1.1 bn GEL) of the total turnover of the sector;

There are only six black or red companies in another sector of strategic importance – Information and Communication. However, their total share of the sectoral turnover is more than 14 %. Interestingly, in the field of mobile communications, Russian-owned Beeline controls 23.9 % of the market, which is a significant size considering the short period upon entering the local market.[7]

The companies under the full or partial Russian influence firmly occupy 9 % of the Georgian businesses. At first glance, this number seems quite low; yet, as we have included only a limited number of companies (Category 1 and 2) in our analysis, and smaller companies would have certainty exposed a large number of red and black companies as well, the real Russian footprint could be even larger. The Russian dominance exposes a significant growth dynamic once the leading economic sectors are considered, and have already approached an alarming threshold. In some sectors, the percentage of the Russian footprint is far larger than the nationwide average, often represented by a handful of companies (e.g., two companies in the energy sector controlling 25 % and two companies in agriculture with 18 %). Furthermore, in almost all dominated sectors, “Russian influenced” companies enjoy the exclusive role of natural monopolies, thus dictating price conditions and fully in control of the “rules of behavior” in the sector. Thus, it can be agreed that 9 % of the national turnover under Russian control can be accepted as the crossing line, beyond which begins the area of heavy and dangerous economic dependence.

Media Analysis

Due to the immense importance of free media in the overall development of democratic institutional dynamics, we include a brief analysis of the media sector, its major actors, and tendencies. It allows us to grasp the depth and gravity of political influences on the sector and establish linkages to Georgia’s overall institutional dynamics, often driven by hidden and illicit interests of particular business or political circles.

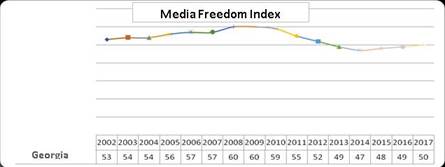

According to Freedom House, Georgia ranks best among its neighbors regarding media freedom, with its worst ranking in 2008 and the best one in 2014 (see Figure 7).[8] Despite this, with its highest index of 47, Georgia still lags behind the Eastern European countries (index 30).

Figure 7: Georgia in the Media Freedom Index.

In the course of media sector analysis, we were able to identify major TV and Radio operators, their revenue sources, the structure of ownership, and market share dynamics between 2012 and 2018.[9] Based on the preliminary assessment of the market revenue distribution, all media actors reaching over 2 % of media market share had been selected for further analysis.[10] Out of seven major TV broadcasters, TV-Imedi, which is directly associated with the ruling party and government, owns a share of 22.7 % of the media market. Although owning less than 1 % of the market share, one more TV-company, Media Union Objective, was additionally selected due to its direct and open activities linked to spreading Russian narratives and supporting the pro-Russian political message. One of its founders is Irma Inashvili, General Secretary of the pro-Russian political party Patriots’ Alliance. Objective’s incomes grew exponentially from 2012 (government change in Georgia) to 2018 from 134,000 GEL to 1.9 mln GEL, of which 1.35 mln came from private donations. The same can be said with regard to radio broadcasting, where 11.6 % of the market is held by Radio-Imedi, and 0.4 % by Radio-Objective. As for the degree of Russian influence, TV-Imedi was classified as ‘red’ due to the dual (Russian and GB) citizenship of its two owners, Ia Patarkazshvili and Liana Zhmotova. Another media player, the MediaNetwork, received a loan from Russian VTB bank in 2016, and thus was coded ‘red’ as well.

Russian Economic Footprint and Democratic Institutions

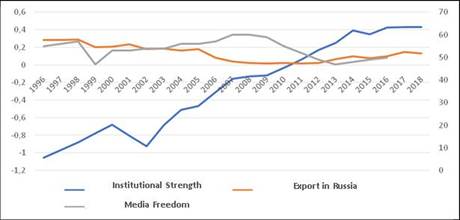

This section presents a regression model created to test the dependence of democratic development (institutional strength) on the Russian economic footprint in Georgia. We will use the share of the export to Russia in overall export as the key explanatory variable and the strength of democratic institutions and media freedom as the dependent variables (Figure 8). To measure the media freedom, we will use the Freedom house measure,[11] while the institutional strength will be measured using the World Bank worldwide governance indicators:[12]

- Voice and Accountability

- Political Stability

- Government Effectiveness

- Regulatory quality

- Rule of Law

- Control of Corruption.

Figure 8: Media Freedom Index, Institutional Strength and Export to Russia.

As seen in Figure 8, since 1996, the institutional development was generally positive, except for the visible slow in the last four years. Media (press) freedom similarly entered in decline since 2015, and the Export to Russia, close to zero from 2006 to 2013, exhibited rapid growth of 13 % in 2018.

The selected institutional variables are standardized and vary between -2.5 and 2.5, with the higher result indicating better institutions. To measure institutional strength, we calculated an average index of all six factors. In addition, six indicators were grouped in three groups: the first and the second formed the group of political institutions; the third and the fourth defined the group of administrative institutions; and the last two covered legal institutions. As for the Media (Press) Freedom indicators, we used the Freedom House index, which places countries in three tiers: tier 1 for free media countries (with index from 0 to 30), tier 2 of countries with partially free media (31 to 60), and tier 3 of countries with no media freedom (from 61 to 100).[13]

The application of the regression model to test the interrelation between these variables provided the following results. The regression in the first and second columns includes the average strength of institutions as the dependent variable and the export share to Russia in the overall export as the control variable. The second regression model in row 3 additionally included the lagged GDP. The regression results indicate a negative relationship between exports to Russia and institutional quality. The regression in the fourth, fifth, and sixth rows have political, administrative, and legal institutions as the dependent variables. As clearly visible, the growth of exports in Russia has a negative impact on administrative and legal institutions and no influence on political institutions. Having media (press) freedom as the dependent variable, the sixth column does not yield any statistically significant relation.

It should be noted that this regression model has certain limitations, that include a relatively small number of observations (23 for the first five dependent variables and 22 for the sixth one – media freedom), and can be balanced by a larger period of observation and data from other countries. Time series and cross-section would generate panel data that would increase the quality and validity of the generated results.

Conclusion

The state’s ability to sustain effective institutions capable of withstanding external (Russian) pressure and minimize Kremlin’s influence politically, institutionally and economically, constitutes the critical hallmark of the countries candidates for EU or NATO membership. Having a free, diversified, and stable economic system is the ultimate objective in the economic dimension of Georgia’s aspirations to align with the EU in legal, trade, energy, and social affairs. Towards that goal, the study presented here aimed to test the validity of Georgian commitments by looking particularly at the patterns of Russian influence over Georgia’s demo-

Table 8. Regression Model.

| Variables | Export | ladgdp | Constant | R-squared |

| (1) Institutions | -0.0420*** (0.00826) |

| 0.290** (0.131) | 0.552 |

| (2) Institutions | -0.00529** (0.00249) | 0.000460*** (2.19e-05) | -1.367*** (0.0839) | 0.980 |

| (3) political | 0.00304 (0.00412) | 0.000299*** (3.63e-05) | -1.292*** (0.139) | 0.856 |

| (4) administrative | -0.0124** (0.00483) | 0.000503*** (4.25e-05) | -1.085*** (0.163) | 0.949 |

| (5) legal | -0.00656* (0.00376) | 0.000577*** (3.31e-05) | -1.725*** (0.127) | 0.972 |

| (6) free press | -0.236 (0.177) | -0.00449** (0.00184) | 68.11*** (6.590) | 0.288 |

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

cratic institutions via intensive analysis of Russia’s economic footprint in the country. It was conducted in a sequence of steps. The first objective was to identify major economic sectors in the country and identify the major companies in each relevant sector fully or partially exposed to Russian influence. Out of eight sectors identified (Manufacturing, Trade, Agriculture, Transport, Communication, Energy, Construction, and Finances), the Russian financial investments predominantly went into Finances, Manufacturing, Construction, and Communication. However, it has to be reminded that the statistics shown by the FDI forms only a fraction of the entire Russian capital flows invested in Georgia due to the possibility of investments via third countries and offshore companies. As the 2020 Deliverables Report clearly states, the trade with other Eastern Partnership countries significantly decreased due to drastic sales of Russian made products in Georgia.[14]

The manufacturing industry is by far the leading branch in exporting goods to Russia. Serious questions arise in connection to multiple projects launched in the energy sector, as they exhibit close to zero feasibility and serious risks of corruption.[15] Similarly to 2006, Georgia approached a point at which the possibility of a Russian embargo could heavily hit the national economy, causing devastating effects and creating conditions of mounting political pressure from the Kremlin. Likewise, the exponential growth of visitors from Russia dramatically increased the share of Russian tourists in the overall tourist number and increasingly put the tourism branch under Russian strain. Almost one third (114 out of 415) of the major Georgian companies expose fully or partially linkages to Russia and occupy an average of 9.2 % of the national business turnover. In some sectors, the gravity of domination by Russia-linked companies is rather alarming (Mining – 63.4 %, Energy – 36.6 %, Agriculture – 24.7 %). Other sectors of strategic importance, such as Information and Communication, expose an ever-growing rate of influence (14.5 %). The developed regression model that put three categories of state institutions (political, administrative, and legal) in relation to exports to Russia and national GDP revealed a clear statistical dependence between the increase of exports and the decline of institutional strength in Georgia, with no statistical effects to media freedom whatsoever.

The general conclusion drawn from the study is that Georgia already reached a point of heavy economic dependence from Russia, which over proportionally affects several key industries of the national economy and continues to expand in some sectors of strategic importance. The Russian footprint located at the level of 9 % of national business turnover is already a redline and the statistical models that capture the interrelation between the growth of Russian economic influence and the decline of the institutional quality clearly confirm the mentioned threshold. Much has to be done to reverse this trend and bring Georgia back to a clear path of minimizing Russia’s footprint, making credible efforts to increase resilience both in economic and political dimensions.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

About the Authors

Shalva Dzebisashvili was awarded a doctoral degree at the Institute for European Studies (IEE-ULB, Brussels) in January 2016. In 2008–09 he successfully completed an MA course in Strategic Security Studies at the National Defense University, Washington DC, and consequently took over the position of Senior Civilian Representative of Georgian MOD (Defense Advisor) to the Georgian Mission to NATO. From 2003 to 2012 and from 2016 to 2019, he served at various senior defense policy and planning related positions at the Georgian Ministry of Defense. He is an associate professor and the Head of the International Relations and Political Science Program at the University of Georgia, a member of various Georgian non-governmental organizations and think-tanks such as the Civil Council on Defense and Security (CCDS) and the Georgian Strategic Analysis Center (GSAC). E-mail: kartweli@yahoo.de

Rezo Beradze holds a MA degree in Economics from the International School of Economics in Tbilisi, Georgia (ISET) and an MSc degree in Financial Mathematics from the University of Sussex. He is an experienced financial and data analyst with a demonstrated history of working in the public and private sectors. Currently, he is a data analyst at the National Bank of Georgia, working on the implementation of the XBRL (eXtensible Business Reporting Language) for the Georgian financial sector. Since 2016, Rezo has been actively working as a lecturer at various Georgian universities teaching data related subjects. His research interests are in development economics, financial economics, and data analysis.

Irakli Gabriadze is a PhD student in the Faculty of Economics at Tbilisi State University. His primary research interests are in development economics, economic growth, transition countries, institutions, and political economy. Recently, he became head of the Analysis, Monitoring, and Evaluation department at Enterprise Georgia. Also, Irakli is an invited lecturer of Macroeconomics and statistics at the University of Georgia.

Suzana Kalashiani has 12 years of experience in the field of journalism, social research, and media communications in Georgia, working in the capacity of a project coordinator of “Russian Economic Footprint in Georgia and influence on Georgian institutions.” Earlier, she has been involved in different projects focusing on combating anti-Western propaganda in Georgia and increasing awareness about the EU-NATO-Georgia relationship.

Mirian Ejibia is a MA graduate from the International School of Economics in Tbilisi, Georgia (ISET). He gained extensive professional experience in reporting and financial analysis while working for the In-depth Reporting and Economic Analysis Center. He also developed full proficiency in data analysis and web application programs and currently works as a full-stack developer (ERP system) at BSC LLC.

&sid=757292&f=revenue&exp=tv&sid=757293.

house.org/reports/publication-archives.

governance/wgi/.