About the authors *

Introduction

This research paper discusses the Mobile Learning Environment (MoLE) Project, a unique and ambitious effort sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Coalition Warfare Program (CWP) in partnership with over twenty nations. The mobile learning project explored the usefulness and effectiveness of using mobile technologies as a tool to support training activities in medical stability operations. This article discusses the importance of employing global research ethics and social responsibility practices in the testing and evaluating of science and technology projects. It provides an understanding of research ethics requirements and looks at how the technical challenges were applied within a global framework. Finally, it showcases an integrated application of a mobile capability in accordance with a myriad of research ethics guidelines and concludes with the accomplishment of evaluating this global capability.

Research Design

Science and technology (S&T) research has played a significant role in developing new technologies that benefit both society and the defense sector. There are many positive impacts that have resulted from such research, and the benefits have revolutionized our way of life. However, this is not always the case across all fields, and there are numerous examples of ethical misconduct in social and behavioral sciences and humanities research. Some researchers in these disciplines at times assert that regulations for the protection of human research subjects do not apply to their work in the same way that they apply to scientific or medical research. However, a close reading of most regulations regarding the involvement of human beings as research subjects will find references that state otherwise.[1] Ethical conduct is an essential element in all scientific research, and is necessary to foster collaboration, cooperation, and trust. It is imperative that research be socially responsible in order to make advancements in scientific knowledge that both protect and benefit the public.[2]

Research has been defined as a process of systematic investigation that includes research development and testing and evaluation activities that are designed to develop or contribute to generalized knowledge.[3] A human subject is defined as an individual who is or becomes a participant in research, either as a recipient of an article being tested or as a control. With such a broad definition, researchers should ensure that all moral and social dimensions are considered when a research project involves any interactions with humans. During the development stage, the project should incorporate a “gate-keeping” mechanism into the planning activities that demonstrates an endorsement of ethical practices, solid research methodologies, and applicable professional standards. For cooperative research, the project’s planning activities need to adhere to each of the institution or country’s research ethics requirements to ensure that the project takes the moral and social dimensions into account.[4] Therefore, when conducting research, three components are required in the research design:

- The Human Research Protection Program, which ensures that the researchers promote the integrity of the research and safeguard against any misconduct

- A Data Collection Plan, which will ensure that there is a clear understanding of the research objectives and develops trust in the data collection process

- The Data Analysis and Interpretation Process, which builds ownership across the research project and provides safeguards against any misconduct or impropriety that might reflect on the researchers or organizations involved.[5]

Human Research Protection

Human subject research is research that involves a living individual about whom an investigator obtains data through interaction. This interaction may include, but is not limited to, any type of communication—such as surveys, emails, Internet, phone interviews, face-to-face conversations, etc.—between the individual and the researcher.[6] Human research also includes risk management and the achievement of research objectives in areas relating to human safety, security, legal, and regulatory compliance and governance.[7] Human research protection includes a code of ethics to preserve individual autonomy, confidentiality, integrity, privacy, security, and respect while minimizing risk and discomfort to the research subject. Any data collection procedure from an individual, directly or indirectly, should incorporate this ethical code within its informed consent document. This written document is viewed as a truthful and respectful conversation that outlines the research approach, and sets forth the rights and responsibilities of both the researcher and the individual subject.[8]

Data Collection

Ethical issues in data collection refer to the need to guard against the collection of harmful or identifying information. To ensure that unnecessary data is not collected—e.g., data that will not be used as part of the analysis or is not required for research objectives—extensive collaboration is needed among the research team to ensure the data collection strategy is understood and accepted. A concerted effort is required to guarantee for all the prospective research participants from whom the data is being collected that the information being collected will not constitute an intrusion into their personal life, the data will not contain any identifying information without consent, and that each person participating in the research has the right to not answer any questions without reproach.

Surveys and questionnaires have their own ethical issues, since the collection process, especially using technology-enabled capabilities, has the potential to link identifying information to the response. Researchers should be conscious of the potential for this to be intrusive, and should seek to minimize any intrusion. The confidentiality of the data must be respected, and positive measures must be taken to protect it.[9] This requires the research team to identify any potential risk related to the privacy of the individuals and to convey this as one of the primary components in the informed consent. Therefore, from a data collection standpoint, the informed consent should identify:

1. How the research protects the anonymity of the individuals

2. The testing process, including roles and responsibilities

3. The expectations of the individual research subjects

4. The evaluative process

5. How data will be shared collectively to support other research initiatives

6. How ownership of the data collection process will ensure anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality.[10]

Data Analysis and Interpretation

At the outset, the link between the terms ethical and statistical is not self-evident. The Collins English Dictionary & Thesaurus defines statistics as a “numerical fact collected and classified systematically, and the science of classifying and interpreting information.” The definition of ethics is the “conscience, moral values, principles, standards and rules of conduct.” Although there is not an apparent connection between statistics and ethics, then, the definition of ethics (i.e., rules of conduct) and statistics (i.e., fact collection and classification) is the key to the relationship.

Ethical issues may arise in data analysis and interpretation. Researchers should show caution during data interpretation. Data analysis should be based on sound statistical research practices leading to conservative data interpretation – which is to say, an interpretation that does not overreach or claim the data are more significant or important than they really are.[11] Even within this paradigm, the interpretation of the same data can take different pathways, none of which may be unethical. Differences in data interpretation may well benefit the scientific process and allow researchers to capitalize on the important debates that lead to new technologies.

Highly collaborative projects, especially those that are involved in collecting both qualitative and quantitative data, must engage co-researchers during the data analysis, interpretation, and report writing process to preserve the integrity of the project’s results and to ensure impartial interpretation of the data. This was particularly important in this project, given the global nature and cultural diversity of the participants. To ensure reciprocity, all of the organizations involved should receive some benefit from the research, as well as have an opportunity to provide input into the interpretation of the analysis. The research results should reflect openness, sensitivity, accuracy, and objectivity in the choices of analysis and dissemination, to ensure that the project respects the interests of the different groups in society.[12]

Mobile Learning Environment Project

The Mobile Learning Environment (MoLE) was a two-year Coalition Warfare Program (CWP) Project.[13] It was sponsored by the Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe (CNE); Commander, Naval Forces Africa (CNA); and Commander, Sixth Fleet (C6F). In addition, it was co-sponsored by the Deputy Director, Joint Staff (J-7) for Joint and Coalition Warfighting (DD J7 JCW) and the Joint Knowledge On-Line (JKO) Director. The CNE-CNA-C6F Deputy Director for Training envisioned that a mobile learning capability could help address the significant challenges associated with training and communicating in the largest maritime area of operations where there are also the challenges of low bandwidth, limited Internet connectivity, and limited infrastructure. The DD J7 JCW JKO Director viewed mobile technologies as a critical step in meeting his organization’s requirement to facilitate and provide training to the U.S. and its multinational partners.

The basic concept was that the MoLE Project would leverage the global cellular network infrastructure, mobile technologies, and emerging mobile applications/service models to build a mobile learning capability that could be integrated into the DD J7 JKO portal. It would provide the foundation for conducting a proof of concept for evaluating a mobile learning solution for meeting emerging training requirements that not only exist in the sponsoring organizations, but also in many related departments, initiatives, and partnerships.

Through the proof of concept it would demonstrate an enhanced level of interoperability and yield significant benefits to all the global partners involved by providing general and medical education and training to military and related civilian personnel of countries in need of humanitarian and civil assistance, joint exercises and force training, or other types of on-demand training. This would, in turn, be shared by the international community to support their medical education and training as well as initiate the development of a sustained capability within their own countries’ defense learning organizations.

In order to support the MoLE Project’s goals and objectives, a Testing and Evaluation Working Group was established, which consisted of representatives from each of the twenty-two participating nations. The working group was divided into three teams to address some key challenges related to research ethics, specifically: human research protection, data collection, and data analysis and interpretation.

Human Research Protection Approach

As a cooperative research project, MoLE faced several challenges, since it involved incorporating twenty-two institutional requirements as well as country-specific guidelines. During the planning phase, a human research protection team was established to ensure that the research ethical requirements of each institution were identified and that subject matter experts were involved to ensure a thorough understanding of the applicable directives.

There are several key U.S. directives related to the protection of human subjects and adherence to ethical standards in DoD-supported research, which have been cited above. Collectively, these guidelines employ the ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report to create a foundation for protecting individuals involved in research, which includes respect for persons, education and training, informed consent, vulnerability of individuals, collaborative research, etc. However, since MoLE was a research project conducted in an established educational setting that involved “research conducted on the effectiveness of or the comparison among instructional techniques, curricula or classroom management methods,” it was exempt from a rigorous human research subject review.[14]

A review of the U.K. requirements stated that research involving human participants undertaken, funded, or sponsored by the Ministry of Defense (MoD) must meet acceptable ethical standards, and that these ethical standards are upheld by the MoD’s Research Ethics Committees. Their Joint Services Publication (JSP) sets out in the MoD instructions the requirements for the ethical conduct and treatment of human participants in research (both clinical and non-clinical) and the ethical treatment of human participants. The JSP states that the directive applies to the conduct of research to collect data on an identifiable individual’s behavior, either directly or indirectly (such as by questionnaire or observation). Thus, the rule was applicable to the MoLE Project.

In ensuring that the project met the European Union’s research requirements, several documents were used as reference, specifically the European Union’s Data Protection Requirements, EPIC’s Privacy and Human Rights report, Solveig Singleton’s article on data privacy in the United States and Europe, and EU Data Protection Directive 95/46/ED.[15] The basic ground rules for privacy state that all individuals involved in a research project need to be informed about the planned research use of collected data, regardless of the type of data collected. If a survey is planned within the project, individuals need not only to be informed of how their data is planned to be handled but also must be given the opportunity to provide appropriate authorization. In addition, the survey design must guarantee that only data specifically required for the purpose of the research project will be gathered, unless clearly stated otherwise.

After careful consideration of all the aforementioned documents and directives, and email exchanges among the international participants, it was determined that the most restrictive guidance was that from the EU; therefore, an informed consent would be required that incorporated both U.S. and EU ethical requirements. The MoLE Informed Consent was developed to include all research protocol areas: Introduction, Purpose of the MoLE Project, Duration of Participant Involvement, Procedures, Testing and Evaluation Process, Risk and Discomforts, Potential Benefits, Voluntary Participation and Withdrawal, Confidentiality, and Consent of the MoLE Individual.

Data Collection, Analysis, and Interpretation Approach

At the project kick-off meeting, the Testing and Evaluation Working Group held a rigorous session to develop a stage-gate approach to ensure that ethical practices were utilized throughout the data collection, analysis, and interpretation phases of the project. The participants were separated into three groups so that equal efforts would be placed on the data collection, analysis, and interpretation requirements. However, since this was the first meeting, the focus was changed to concentrate more on “what should be asked” and “what data should be collected” in order to achieve success, rather than on how the collected data would be analyzed or interpreted. As a result of the collaboration, the team decided to place concerted effort on:

1. What types of questions should be asked

2. The testing and evaluation process, including roles and responsibilities

3. Research expectations

4. The evaluation process

5. How the data will be shared during the analysis phase

6. How transparent data collection would ensure anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality.

Research Strategy

After this initial meeting, the Testing and Evaluation Working Group focused on addressing issues relevant to determining how the MoLE Project would measure whether it had met its goals and objectives. The working group was divided into three teams to ensure the key elements in evaluating the proof of concept were identified and resolved (i.e., human research protection, data collection, data analysis and interpretation). The three teams each collaborated via quarterly teleconferences and Web meetings, with the exception of the human research protection team, who collaborated on a weekly basis to ensure that all ethical requirements were identified and documented.

Human Research Protection

Subsequent to the review of pertinent documents, ranging from “the involvement of individuals in research” to “information and data collection requirements,” the human research protection team developed a draft MoLE Proof of Concept Informed Consent, which would serve as the written agreement between the researchers and the individuals. It was then emailed to all Testing and Evaluation Working Group members for review and comment in order to ensure a complete understanding of the research protocol. Comments were then incorporated into the document and presented at a three-day Testing and Evaluation Working Group meeting to ensure that the document reflected the actual state of the testing and evaluation process. This review process ensured that the research protocol was totally accurate, including how testing and evaluation would be carried out, what the duration of involvement and confidentiality would be, etc. The revised informed consent form was subsequently sent via email to over forty international delegates for their final review and feedback. The email also requested each delegate to consider if a version of the informed consent statement should be translated into their native language to ensure complete understanding of individual requirements and expectations. The informed consent form was thus made available in English and also translated into Spanish and French.

Data Collection, Analysis, and Interpretation

During the initial project meeting, the Testing and Evaluation Working Group members that were not on the human research protection team formed small groups to determine what types of data should be collected in order to meet project goals and objectives. Each of the groups provided recommendations on the types of data that could be collected and operational measures for determining effectiveness and performance. However, since the mobile content was still being developed, it was not yet possible to finalize these guidelines. In focusing on the core goals and objectives of the MoLE Project, the two teams determined that data collection should focus on four themes, as shown in Table 1. An email was sent to each of the working group members asking them to provide five questions they would ask if they were developing the survey. As a result, an average of 150 inputs per term of reference (in addition to over twenty other potential questions) were identified.

Table 1: MoLE Terms of Reference.

Term of Reference | Meaning |

Accessibility | The degree to which a mobile training application is available to the user |

Self-Efficacy | A user’s belief that he/she is capable of producing the desired outcome of the task required |

Usefulness | The benefit or availability of mobile technologies in providing training |

Utility | The effectiveness, or practicality, of using mobile technologies in providing training |

Once the Medical Content Working Group identified the medical content, a three-day meeting of the Testing and Evaluation Working Group was convened, which included the Medical Content Working Group leads. The purpose of this meeting was to:

1. Inform the Testing and Evaluation Working Group of the medical content decision

2. Identify the scenarios and vignettes to ensure the proof of concept included both medical and non-medical participants

3. Identify the survey questions that would be asked as part of the scenarios and vignettes

4. Collaborate on the transparent data collection strategy

5. Review the MoLE PoC Informed Consent and how it fits into the data collection strategy

6. Develop the MoLE Testing and Evaluation Plan.

Figure 1: MoLE Proof of Concept Process.

After the first day, the group was divided into two groups: the data collection team, and the data analysis and interpretation team. The data collection team, in collaboration with the Medical Content Working Group leads, developed a storyboard of how the data collection process (e.g., survey and transparent digital data) would integrate with the medical content. In the meantime, the data analysis and interpretation team focused on the how the data would be statistically displayed as well as on how the data could be made available to international researchers for follow-on research initiatives. At the end, each of the teams, including the human research protection team, briefed the content and technical teams on their results to enable integration into the mobile apps under development.

At the start of the second year, the Testing and Evaluation Working Group convened for a final meeting before the completion of the technical development phase to finalize the data collection, analysis, and interpretation strategy. Discussion focused on refining the process of how the proof of concept would function. Final decisions were made regarding the demographic data collection plan, how individuals would participate in the proof of concept, and the human research protection issues.

Application Development

Tribal Group was responsible for developing the mobile application based on the requirements from each of the three working groups: Learning Content, Technology and Transition, and Testing and Evaluation. The Learning Content group worked with a wide range of medical and training stakeholders to design, convert, import, and create mobile content to support the needs of the target users. The Technology and Transition group developed a cross-platform toolset that enabled mobile learning content to be deployed to apps on both Android and iOS (Apple) platforms, and worked with Joint Knowledge On-line (the US DoD e-learning platform) to integrate the mobile platform with their back-end infrastructure. The Testing and Evaluation group ensured that the testing and evaluation process was carried out as planned, specifically regarding the ethical research issues and human research protection issues.

Evaluation Process

Participation in the MoLE Proof of Concept trial was a two-step approach. First, each organization participating in the project was required to identify at least twenty individuals to participate in the trial. Email addresses of each volunteer would be sent to the MoLE Research Ethics Coordinator, who was the only person with full access to all volunteer contact details. Using a tool developed by Tribal, the Research Ethics Coordinator would generate a unique personal identification number for each volunteer, and email each one with a welcome message containing all instructions for participation. This included a link to their registration page, their personal identification number (PIN), and additional links to support their involvement (i.e., introduction video, user guide, and detailed overview and installation guide). The email also provided a link to the MoLE Registration Site. In the Registration Site, no data could link the PIN with the email or name of the individual. On two or three occasions, volunteers sought support from the MoLE Technical Help Desk and inadvertently included their personal identification number. In such cases, they were reassigned another PIN to ensure their anonymity. Once the app was installed, they could participate in the MoLE Proof of Concept trial. When the trial had ended, the Research Ethics Coordinator deleted all databases that contained any references to email addresses and PINs.

As Figure 1 shows, the testing and evaluation process was broken down into six steps. First, an email announcement would be provided to each individual. The individual would register online, install the app, and then activate their app using their personal identification number. Each individual was afforded the opportunity to become familiar with the app before starting the evaluation.

During the online registration, each individual was required to acknowledge the MoLE PoC Informed Consent and complete the demographics questionnaire (see Figure 2). Without acknowledgement, they were unable to validate their PIN or activate the mobile app.

On completion, the PIN would be activated, and the user would be able to download the Global MedAid app from their local App Store, and register using their unique PIN. This PIN only carried a national identifier (to permit localization), and no personally identifying data.

Question | Responses |

Age | less than 20, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50+, no answer |

Gender | Male, Female |

How proficient are you in English | Beginner ... Advanced |

Are you using your own personal smartphone for the purpose of this trial? | Yes, No, No Answer |

How comfortable are you with using the mobile device that’s running the MoLE app? [Beginner to Advanced] | Beginner ... Advanced |

Have you previously been involved in humanitarian assistance or disaster relief operations? | Yes, No, No Answer |

What is your professional expertise? | Medical, Rescue, Training, E-learning, Other |

Have you taken the Trafficking in Persons (CTIP) course within the last two years? | Yes, No, No Answer |

Figure 2: Demographic Data.

Once the Global MedAid app was installed, volunteers were encouraged to familiarize themselves with the app and explore its features. When they were ready to begin the evaluation, they launched a specially designed “evaluation layer,” which gave them specific tasks to complete within the app, following pre-defined medical scenarios/vignettes. Their use of the app was monitored (transparent data), and their feedback on the task was collected via an in-app survey. These data were then synchronized back to the project website and collated.

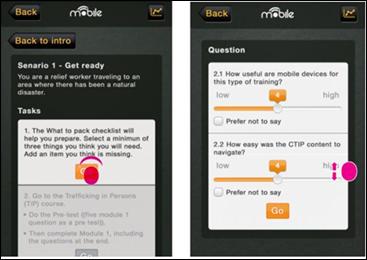

Figure 3 shows a sample page from the evaluation survey. The volunteer is asked to complete a task, and on completion is asked to answer a few questions. Most of the questions were completed with a “slider,” allowing selection against a seven-point Likert scale. All questions offered the option of not responding, and required an active effort to select an answer.

Volunteers were asked to complete three vignettes/scenarios representing three different ways that the Global MedAid app might be used: one before deploying on a humanitarian mission, one en route, and one on arrival. Each scenario was structured in the same way, giving the user a series of tasks, tracking their activity, and recording their answers to specific questions. At the end, they were asked one final set of questions requiring text input, and offering a more open format for responding.

At a pre-defined date the proof of concept phase concluded, and no more tracking data or survey responses were collected. A new version of the app was subsequently released that automatically upgraded, removing the evaluation survey and registration requirement of the app.

Figure 3: MoLE PoC Response Format.

Once the proof of concept evaluation was completed, the Testing and Evaluation Working Group initiated an analysis of the data in which several group members independently conducted their own analyses. In addition to the internal analysis that was being conducted, several outside resources were used to provide independent analysis of the interpretation of the data. In areas where there were disagreements, additional analysis was conducted to help identify the potential disparities in the analysis and draw appropriate conclusions. The results of this evaluation will be reported in a separate report. This article aims to describe the process and clarify the steps taken to ensure that clearly defined research ethical standards were observed and that volunteers’ data were protected.

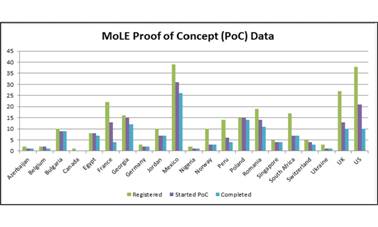

Volunteer Numbers

The data showed that 268 test subjects had registered. Of these, 177 (66.4 percent) started the proof of concept trial, and 137 (51.1 percent) completed the trial. These subjects came from twenty-one countries (Figure 4). Of these participants, 70.9 percent used their own mobile device, while 29.1 percent borrowed a colleague’s device. A majority (63 percent) were using an iPhone 4 or 5, and 37 percent used an Android device (running version 2.2, 2.3, 3 or 4).

The individuals’ professional expertise, based on the demographics survey, showed that 34.2 percent had medical experience, 26 percent were involved in e-learning, 25.3 percent identified their professional expertise as “other,” 11.2 percent conducted general training, 1.1 percent were involved in rescue efforts, 2.2 percent were involved in rescue operations, and 3 percent declined to answer the question. A majority of the individuals were using the app in English; German, French, Georgian, and Spanish versions were also available.

Figure 4: Proof of Concept (PoC) Participants.

The Wider Project

The primary purpose of this project was to explore the utility and effectiveness of using mobile technologies in security training and then to create a transition strategy that moves mobile learning and training into the mainstream of defense training for all of the international partners involved in the project. This process has already started, and several partners are adopting some of the system and processes that will include some of the content created by the project into their mobile training programs. An extensive publication has been produced about the project, so that learning and development, education and training, medical training, electronic learning and mobile learning, research and development, and testing and evaluation professionals can gain insight into what worked best in providing a mobile learning (m-learning) capability that was learner-centered (i.e., built on the skills and knowledge of the individual/teams), knowledge-centered (i.e., providing educational content that is factually sound), and community-centered (i.e., promoted the sharing of knowledge and collaboration).

Conclusion

The Mobile Learning Environment (MoLE) Project, as a global research initiative, demonstrated that project goals and objectives can be fulfilled by employing ethical and socially responsible practices. Given the diverse group of stakeholders, there was considerable complexity involved in developing and implementing a testing and evaluation strategy that incorporated research ethics guidelines. Although there were many challenges in integrating ethical research requirements into the technical interfaces, with careful management and an effective stage-gate approach, these challenges can be dealt with clearly and effectively.

* Jacob Hodges is an independent advisor on innovative approaches to education and training. He served as Project Research Coordinator for the Mobile Learning Environment (MoLE) Project, and provided program management and technical support to the Project Manager, technical support to the Testing and Evaluation Working Group, and assisted the MoLE Science & Technology Coordinator in conducting S&T reviews. Geoff Stead is Head of Mobile Learning at Qualcomm. He has been active in mobile learning since 2001, innovating and building technologies to support learning, communication and collaboration across the globe.

The authors would like to acknowledge the subject matter advice on EU/UK Research Ethics provided by Dr. Andrey Girenko (Deutsche Forschungszentrum für Künstliche Intelligenz), Dr. Andrea Loesch (GIRAF PM Services), Dr. Venkat Sastry (Defense Academy of the United Kingdom), Dr. Tammy Savoie (J-4, USAF), the MoLE Testing & Evaluation Working Group Members, and the project’s international partners.

The work discussed in this article is related to Department of the Navy (DoN) Grant (N62909-11-01-7025) and two DoN Contracts (N68181-11-P-9000 and N68171-12-P-9000), which were awarded by the Office of Naval Research Global and funded by the Coalition Warfare Program. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not represent or reflect the views of any government agency or organization that participated in the project or is mentioned herein.

[1] Code of Federal Regulations, Title 32 – National Defense, Part 219: Protection of Human Subjects; available at http://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/32/219. See also U.S. Department of the Navy, SECNAVINST 3900.39D, “Human Research Protection Program” (6 November 2006); available at www.fas.org/irp/doddir/navy/secnavinst/3900_39d.pdf.

[2] David B. Resnik, The Ethics of Science (New York: Routledge, 1998).

[3] National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, “Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research,” Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication No. (OS) 78-0012 (18 April 1979); available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/belmont.html.

[4] Judith P. Swazey and Stephanie J. Bird, “Teaching and Learning Research Ethics,” in Research Ethics: A Reader, ed. Deni Elliott and Judy Stern (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1997).

[5] John W. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2009).

[6] SECNAVINST 3900.39D.

[7] ANSI/ISO/ASQ, Quality Management Systems – Guidelines for quality management in projects (e-standard), International Standard: ANSI/ISO/ASQ Q10006-2003(E) (Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press, 2006).

[8] Robert G. Burgess, The Ethics of Educational Research (London: Routledge Falmer, 1989).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Mark Israel and Iain Hay, Research Ethics for Social Scientists: Between Ethical Conduct and Regulatory Compliance (London: Sage, 2006).

[11] Resnik, The Ethics of Science.

[12] Burgess, The Ethics of Educational Research.

[13] Jacob R. Hodges, Mobile Learning Environment (MoLE) Project: A Global Technology Initiative (20 February 2013); available at https://www.createspace.com/pub/simplesitesearch.search.do?sitesearch_query=Mobile+Learning+environment&sitesearch_type=STORE.

[14] Code of Federal Regulations, Title 32 – National Defense, Part 219: Protection of Human Subjects.

[15] Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), Privacy and Human Rights Report 2006: An International Survey of Privacy Laws and Developments (Washington, D.C.: EPIC, 2007). Solveig Singleton, “Privacy and Human Rights: Comparing the United States to Europe,” Cato Institute White Paper (1 December 1999); available at www.cato.org/pubs/wtpapers/991201paper.html. EU Data Protection Directive 95/46/ED, 24 October 1995; available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31995L0046:en:HTML. For governing directives for U.S.-based researchers involved in the project, see Department of Defense (DoD) Directive 3216.2, “Protection of Human Subjects and Adherences to Ethical Standards in DoD-Supported Research” (7 January 1993); Department of Defense Instruction 3210.7, “Research Integrity and Misconduct” (14 May 2004); and Department of Defense Instruction 5400.11, “DoD Privacy Program” (8 May 2007); all available at www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/ins1.html.