Since human resource management is paramount for achieving defense organizations’ strategic goals, efficient strategy is vital. Consequently, a consistent combination of end-state, strategic goals, consistent actions, and resources to achieve them (interrelated combination of ends, ways, and means) can be considered a primary task for strategic leaders. This seems the appropriate time to examine what strategic leadership means in the military human resource management’s strategy development throughout capabilities-based defense planning processes or, more particularly, which key attributes of a successful strategic leader help them to achieve established end-state and strategic objectives.

This article begins with an overview of leadership theory development and presents a set of main attributes and distinctive characteristics of a strategic leader. Then the discussion turns to outlining the main concepts of capabilities-based defense planning with essential components of military capabilities based on Ukrainian guidelines. The last section presents a study of the role and place of strategic leadership in the formation and implementation of human resource management strategy throughout the capabilities-based planning process.

An introductory study of leadership theory using existing literature from the past century reveals that the understanding of the essence of leadership has repeatedly transformed. Until the end of the 1940s, leadership was considered an internal ability. However, by the end of the 1960s, effective leadership implied a certain behavior style. A further developmental trend of the theory towards the beginning of the 1980s was understanding the influence of unforeseen situations on the manifestation of leadership qualities, the so-called “contingency approach.” Recently, a new trend emerged, i.e., strategic leaders need the vision to develop the main processes entrusted to them for the long term.[1] Furthermore, the ability to focus on future central priorities distinguishes the strategic leader from all others. As Roger Gill pointed out, “Leadership starts with a dream – a vision of what or where we want to be. We pursue that vision through strategies, which are the first step in transforming the dream—the vision—into a reality.” [2]

As John Adair has observed, strategic leadership has military origins: “Originally, strategy … meant strategic leadership – the art of being a commander-in-chief.” [3] The strategic leader is the leader at the highest level, unlike the operational and tactical leaders. If we look at the military sphere, the tactical leader is the unit commander who makes decisions about individual operations and tasks at his or her level, while the operational leader is a higher-level commander who makes decisions about how exactly it is possible to achieve strategic goals with regard to the principles of efficiency, effectiveness, and economy (so-called 3E-principles). At the same time, the strategic leader is already an official of the Defence Minister or the Chief of Staff level, who determines the primary vision of long-term development and future use of the armed forces or its components in the area of state security and defense utilizing his or her strategic thinking.

John Adair differentiated between “strategic thinking” and “other forms of thinking”: the first is “concerned with the important rather than the trivial or mundane, and the long-term as opposed to the short-term.” [4] The focus is on always using strategic thinking, which “is grounded in a strong understanding of the complex relationship between the organization and its environment.” [5] Such ability can help him or her conduct a comprehensive analysis of the necessary information to form a successful long-term development strategy. Proper formation of such a strategy also implies that the strategic leader has such a trait as prudence, namely the ability to work well with risks. Such work involves the timely identification and clarification of all-important risks, their assessment by impact and frequency, as well as the identification of measures to manage them practically. As the authors of the curriculum “Strategic Leadership: The General’s Art” elaborated, “… one of the most important things that a strategic leader must learn is not simply how to think critically, but how to do it well.” [6]

Michael Hitt, Katalin Takacs Haynes, and Roy Serpa, with reference to Ireland, emphasized that effective strategic leaders in the new competitive landscape expected for the 21st century had to: develop and communicate a vision, build dynamic core competencies, emphasize and effectively use human capital, invest in the development of new technologies, engage in valuable strategies, build and maintain an effective organizational culture, develop and implement balanced controls; and engage in ethical practices.[7]

One of the most comprehensive up-to-date sets of qualities, capabilities, and behaviors, which characterize the most effective strategic leaders, is suggested by the Royal College of Defence Studies (Defence Academy of the United Kingdom). It was developed by both staff and members of the 2016/17 course, with the help and support of a number of external experts from across Whitehall and academia.[8] The following strategic leadership characteristics should be highlighted from this carefully compiled list:

Qualities: sincerity, humility, and truthfulness; flexibility; moral courage and boldness; great stamina and resilience in the face of setbacks; self-confidence and an ability to inspire confidence in others, whatever the adversity.

Capabilities: the confidence to operate in uncertainty: an ability to comprehend and handle extreme complexity, to overcome self-doubt and the hesitation of colleagues and subordinates, and to operate successfully in an environment of potential disorder, disunity, uncertainty and ambiguity; the ability to operate under intense media pressure.

Behaviors: a desire to push work across boundaries; a habit of building, leading, and listening to teams.

At the same time, in its Strategic Leadership Primer, the US Army War College provides a list of strategic leader competencies using the “Be, Know, Do” typology. The following competencies can be underlined in this comprehensive list:

BE (disposition – values, attributes), such as a master of the strategic art of balancing ends, ways, and means; comfortable with complexity; high personal stamina – physical, mental, stress management; skilled diplomat.

KNOW (disposition – skills): Conceptual – envisioning; proactive thinking; problem management; critical self-examination; skillful formulation of ends, ways, and means. Interpersonal – communication; inspiring others to act; skillful coordination of ends, ways, and means. Technical – systems understanding: political, economic, cultural, logistical, force management, joint/combined interrelationships, etc.; skillful application of ends, ways, and means.

DO (action – influencing, operating, and improving): provide for the future – visioning (long-term focus, time span, perspective); shape the culture; lead and manage change; practice the strategic art – allocate resources, develop and execute strategic plans derived from the interagency process.[9]

Looking across the existing literature on strategic leadership attributes, the following distinctive feature of the contemporary military strategic leader can be derived: his or her ability to formulate, make, and coordinate strategy as a consistent combination of end-state, strategic goals, consistent actions, and resources to achieve them (interrelated combination of ends, ways, and means). Such ability is vital in fulfilling the main tasks of a strategic leader, which General David H. Petraeus formulated as follows: “The first is to get the big ideas right. The second is to communicate them effectively throughout the breadth and depth of the organization. The third is to oversee the implementation of the big ideas. And the fourth is to determine how the big ideas need to be refined, changed, augmented, and then repeating the process over again and again and again.” [10]

In order to correctly define the role and place of strategic leadership in building a human resource management strategy throughout capability-based defense planning, first of all, it is necessary to clearly define key concepts such as “defense planning process,” “capability” and its basic components, as well as “capabilities-based planning.” Defense planning is carried out to provide State’s defense capabilities by determining the priorities and directions of development of defense forces, their capabilities, weapons and military equipment, infrastructure, training of forces, as well as developing appropriate strategies, concepts, programs, and plans accounting for real and potential threats in the military sphere and financial/ economic capabilities of the State. According to the Ukrainian Defense Planning Guidelines, based on NATO standards, these key concepts are defined as follows.[11]

The defense planning process incorporates consistent actions carried out according to common principles and procedures to determine and create trained and equipped troops (forces) and capabilities. Capability means the ability of military authorities, formations, military units, military educational institutions, and other organizational structures of the Armed Forces or a set of forces to perform certain tasks (ensure the achievement of certain military objectives) under certain conditions, limited resources and in accordance with established standards.[12]

The following eight basic components of military capabilities are decisive for their comprehensive analysis, planning, creation, development, and evaluation:

Doctrinal base – normative/legal and organizational/administrative acts, which determine the principles of functioning and use of troops (forces), as well as ensure the achievement of their necessary capabilities;

Organization – a military organizational structure or its element with the appropriate composition of forces and means to perform assigned tasks that meet the requirements for the particular capability;

Training – a system of appropriate force training, which provides a certain capability, individual and collective training of personnel, as well as training of headquarters and military formations;

Resources’ provision – provision of capabilities with the necessary weapons and military equipment, supplies of material and technical means, as well as financial resources;

Leadership and education – professional development of management at all levels through education, training, experience, and self-improvement in order to develop the most professionally trained leaders;

Personnel – qualified, patriotic and motivated personnel (including military reserves) who meet certain requirements for the capability to perform tasks in peacetime and in special periods successfully;

Military infrastructure – facilities, buildings, structures with related communications (roads) and land, aimed to ensure the performance of troops (forces) tasks for their intended purpose;

Interoperability – the capability to take joint concerted, effective and efficient actions in order to achieve tactical, operational and strategic goals in the defence sphere.

In Ukraine, the capability-based defense planning process is organized as a sequence of actions to perform the following tasks:

defining the goals and main tasks of the implementation of state policy on national security and defense;

assessment of the defense forces’ ability to perform their own tasks;

evaluation of the current military capabilities;

determining the list of necessary military capabilities that will meet existing needs;

determining the list of excessive capabilities;

formation of the need for resource provision for capabilities’ development;

risk management;

planning and programming;

monitoring and control of the established goals’ achievement.

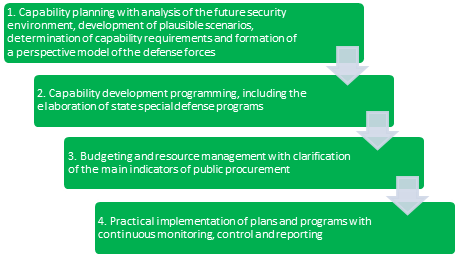

The capability-based defense planning process includes the stages illustrated in Figure 1. Based on them, capability-based planning can be considered as a planning process that involves the development of defense capabilities, including qualified, patriotic, and motivated personnel, in the face of threats and risks in the long perspective within constrained resources.

Experts from RAND Corporation, who in 2019 conducted a study of defense planning approaches used in the United States,[13] distinguished two main approaches to defense planning, namely demand-based and supply-based planning. In this case, the Demand-based approach is divided into capabilities-based planning and threat-based planning. In both approaches, the main actions of the decision-makers remain the same, namely: identification, analysis, and development of requirements; assessment of available capabilities; consideration of existing and possible constraints; risk identification and assessment. It should be mentioned here that these actions may be considered the particular stages of a certain strategy.

Figure 1: Capability-based Defense Planning Process.

With regard to capability-based planning, it is based less on identifying specific adversaries and more on analyzing the full range of capabilities, including qualified, patriotic, and motivated personnel, which are needed in future conflicts to achieve strategic goals. The main goal of this type of defense planning is to create planning structures in the current and future environment with a high level of uncertainty about the current and future capabilities of a potential adversary. Such requirements help ensure the planning structures confirm the necessity of having an effective strategy for human resources management.

After considering the concepts of strategic leadership and the capability-based planning process, we argue that the qualified, patriotic, and motivated personnel forms one of the vital components of the armed forces’ ability to fulfill their tasks and achieve strategic goals. With this in mind, the development and successful implementation of a human resource management strategy in capability-based defense planning are of utmost importance. At the same time, the practical application of the qualities, capabilities, and behavior of strategic leadership ensures the effectiveness of such a strategy.

The concept of Human Resource Management (HRM) has been adopted widely by military leaders and, over time, has been integrated into policy and doctrine formerly used to describe personnel management and administration functions. In the most general sense, HRM is a series of integrated decisions about the employment relationship that influences the effectiveness of employees and organizations.[14] As Henry A. Leonard explicated, HRM “is a fundamentally important institutional capability for all defense organizations, and thus a key element of defense institution building. … Successful strategic human resources systems provide not only for the armed forces themselves, but also for the organizations and institutions that support those forces. Absence or failure of this pillar would be a serious if not fatal flaw in a nation’s overall defense posture.” [15] It should be noted that leadership is a comprehensive concept that includes the psychological aspect of a person’s motivation to be a good example of a citizen who is devoted to his or her country.

Based on the above, the Ukrainian Defense Ministry and Armed Forces nowadays have a significant interest in adapting and transforming their strategic human resources system to align with modern best practices. At the present stage, the main goal of military personnel policy is to create conditions for guaranteed and high-quality staffing of the Armed Forces with trained and motivated personnel capable of performing their assigned tasks,[16] as well as policy developments in recruiting, personnel management, education and training, social and humanitarian support.[17] The necessity of transformation of the military personnel policy in these particular areas is due to the need to achieve the following results:

in recruiting – establishing recruitment units and introducing a Unified State Register of Conscripts;

in personnel management – implementation of military career management related to military rank, rating system, individual career management, and mandatory rotation;

in education and training – alignment of the military education system with NATO standards and formation of an effective system of professional military education, taking into account the experience of combat operations;

in social and humanitarian support – improvement of privileges and social guarantees of military personnel, military salaries, the healthcare system, and a mechanism for housing provision.

As John Chilcot pointed out, “Policy only works if there is a credible strategy to deliver it and strategy demands an achievable policy end-state.” [18] Therefore, it can be argued that the process of developing an HRM strategy represents the military leadership’s strategic vision of development in the field of personnel policy.

Given the essence of the strategy as a consistent combination of end-state, strategic goals, consistent actions, and allocated resources (interrelated combination of ends, ways, and means), the strategy of HRM in capability-based planning can be presented as a set of ten successive and interrelated stages. 1. Defining the strategic objectives, which implement a certain vision to achieve the determined end-state. 2. Analysis of the existing internal and external conditions in the HRM environment. 3. Formation of possible courses of action as ways to achieve the end-state and strategic goals. 4. SWOT analysis [19] of the defined courses of action. 5. Forming a risk management system as a consistent combination of risk identification, classification, assessment (evaluation), and management. 6. Choosing the most effective course of action as a way to achieve strategic goals. 7. Determining the needed resources to implement the selected course of action. 8. Programming the implementation of the course of action. 9. Creation and implementation of effective supportive narrative for internal and external target audiences. 10. Ensuring continuous monitoring of the strategy implementation process, as a combination of intermediate results evaluation and adjustment of existing programs.

The strategic leader has a profound understanding that it is their personal responsibility to set the strategy, direct it and adjust it when necessary.[20] Therefore, the qualities, capabilities, and behavior inherent in strategic leadership play a key role throughout all stages of the formation and successful implementation of an effective military HRM strategy.

The essence of each stage from the above list, with a corresponding explanation of the role of strategic leadership, is presented below.

During the first phase, the end-state and strategic objectives of HRM are determined on the basis of the state policy in the field of security and defense, which together implement the vision of strategic leadership to achieve the end state and must meet the so-called “SMART criteria,” where SMART is an acronym that stands for Specific (must be as clear as possible), Measurable (must be tracked and evaluated), Achievable, Relevant and Time-based.

The strategic goal of the HRM reform is to create a personnel management system based on the principles adopted in the armed forces of NATO member states, aimed at optimally meeting the needs of the Ukrainian Armed Forces (hereafter – UAF) in highly qualified personnel motivated by long contract-based service and able to perform assigned tasks.

The main strategic objectives of the Ukrainian military HRM system are:

implementation of the principles and approaches adopted in the armed forces of NATO member states in military personnel policy;

creation of an effective system of military career management related to military rank, improvement of the military service procedure;

redistribution of the main tasks and functions of the Ministry of Defence and UAF personnel services, as well as official decision-makers;

development of human capital of the UAF, in particular through modernization of education and science, health care, culture, social protection, ensuring gender equality and spirituality;

creation of an efficient and transparent system of military salary built on the hierarchy of military ranks;

establishing a multi-level professional education system in compliance with NATO standards and best Ukrainian and international practices.

The practical implementation of the strategic HRM objectives involves the following tasks:

improving existing legislative norms on the Euro-Atlantic transformation;

ensuring that each service member is aware of the benefits of NATO member states’ principles and approaches;

laying the foundations for the management of the career of service members in the principles of human-centeredness, taking into account gender aspects and mandatory rotation in military positions;

appointment of service members to higher positions and assignment of military ranks solely based on a rating formed under such criteria as the appropriate level of education, personal experience, including in combat, individual capabilities, necessary competencies, and integrity;

ensuring the psychological recovery of staff; restoring and maintaining their mental functions and psychological readiness;

improvement of benefits and social guarantees for military service, the introduction of necessary additional motivating factors, provision of effective mechanisms of control over their implementation;

Implementing updated military training programs, considering NATO combat experience, principles and standards, including on gender issues.

The expected result of the HRM reform implementation is the establishment of appropriate conditions for staffing the UAF with motivated and highly qualified personnel who demonstrate readiness to perform military service according to Euro-Atlantic principles and can perform the assigned tasks.

The distinctive feature of the true strategic leader that is critical at this stage is his or her ability to have a clear vision of the ultimate end state and strategic objectives, as well as the ability to formulate them clearly. At the same time, such a leader must have the moral courage (willingness to stand firm on main values, principles, and convictions, regardless of consequences) to justify his or her values-based and inspirational vision for people, including their supporters and the public.

During the second stage, the analysis of the existing internal and external conditions for the implementation of the HRM process is carried out. Namely, the current and projected impact in the political, economic, social, technological, legal, security, and military spheres. Based on the results of such research, conclusions are formed, and influencing factors are prioritized for subsequent responses (taking into account possible courses of action).

Throughout the third stage, the formation of possible courses of action as effective ways to achieve HRM’s end-state and strategic goals is carried out. It needs to comply with the principles of efficiency and effectiveness, taking into account the possibilities of the efficient application of social, economic, humanitarian, informational, and other tools.

Key for the strategic leader at the second and third stages is the ability to possess and apply the intellectual breadth of a high order beyond normal or corporate mindsets. In addition, a strategic leader at these stages of strategy formation must have a capability characterized as “the confidence to operate in a province of uncertainty: an ability to comprehend and handle extreme complexity, to overcome self-doubt and the hesitation of colleagues and subordinates, and to operate successfully in an environment of potential disorder, disunity, uncertainty and ambiguity.” [21]

During the fourth stage, SWOT analysis of identified courses of action, as detailed research of existing and potential strengths and weaknesses, as well as opportunities and threats, is performed. After conducting such an analysis, possible ways are determined to operate current strengths and weaknesses for the most effective and efficient implementation of opportunities and reduce threats for each course of action identified.

Throughout the fifth stage, a risk management system is created, namely the consistent process of all possible risks’ identification and classification, their assessment, and determination of effective measures to respond to them.

The identification and classification of risks by categories and types are carried out as follows. By categories, risks are divided into external – risks, the probability of which is not related to the performance of structural units and personnel functions and tasks; and internal – risks, the probability of which is directly related to such performance. By types, risks are classified as: personnel risks, which are associated with the training of personnel and the quality of their functional responsibilities (job descriptions), including risks associated with reduced motivation; corruption risks, as a set of legal, organizational, and other factors and reasons that encourage (stimulate) individuals to commit corruption offenses while performing state functions; regulatory risks, which are considered as the risks that arise in connection with the absence, inconsistency or unclear functions and tasks regulation in the legislation; operational and technological risks, which are associated with violation of the established procedure for performing functions and tasks; reputational risks, as actions or events that may adversely affect the reputation, etc.

The risk assessment process involves the following procedures: determining the degree of risk according to the probability of occurrence of risks and their negative impact to effectively ensure the implementation of the HRM process; prioritization of the identified risks for an appropriate response to them. Determining how to respond to identified and assessed (evaluated) risks can be considered as deciding to avoid, reduce, share or accept the risk. Thus, risk avoidance means the suspension (cessation) of activities that lead to increased risk. Risk reduction means taking measures that reduce the likelihood of risk and/or its impact. Risk sharing (allocation) means transferring the risk (part of the risk) to another participant in the HRM process. Finally, acceptance of risk means that no action is taken against it.

The role of the strategic leader at the fourth and fifth stages is to utilize their capabilities to think critically, namely, think clearly, rationally, reflectively, and understand how their decisions ultimately impact the desirable result. It is vital for strategic leaders performing the SWOT analysis and creating an effective risk management system to consider the logical connection between the strategic goal and possible courses of action, as well as to utilize their cognitive skills to identify the relevance of existing arguments for all options.

During the sixth stage, based on the results of the SWOT analysis and risk assessment, as well as testing the political acceptability, feasibility, suitability, sustainability, and adaptability, the most effective course of action is selected as the best way to achieve the end-state and the strategic objectives.

The role of the strategic leader at the sixth stage is utilizing their attribute of possessing intellectual sophistication, such as the ability to full pattern recognition and the capability to identify second, third, and fourth-order effects of the most effective course of action.

In the seventh stage, the needs for all types of resources for implementing the selected course of action are determined based on calculations of available resources, projected additional capacity of the national economy, projected international aid, and other sources.

During the eighth stage, a clear, detailed plan (program) for the implementation of the selected course of action is drafted and approved.

Since, during these stages, a strategic leader needs to combine key attributes of strategic leadership and effective management, the process of resource determination and programming the strategy implementation requires multifunctionality (experience in two or more operational or functional areas and knowledge of more than one domain). As Al Robbert pointed out, “Taxonomies of leadership and management skills are plentiful. … Such taxonomies tend to overlap – those focusing on leadership see management as a subset of needed leadership skills, while those focusing on management see leadership as a subset of needed management skills. … Leadership skills are emphasized in the visioning and motivating roles; management skills are emphasized in the decisional and resource marshaling roles.” [22]

During the ninth stage, a supportive narrative is formed for internal and external target audiences, which justifies the need to achieve the certain end-state and strategic objectives, explains the effectiveness of specific chosen ways to achieve them, and justifies certain amounts of resource costs. Such a narrative aims to motivate the target audience to support the defined strategy and assist in its implementation.

The role of the strategic leader at the ninth stage is to use effectively their ability to communicate with a much broader audience and “to operate under intense media pressure: the spotlights of 24/7 news and public opinion polls are relentless and unforgiving.” [23] Moreover, a strategic leader must be a charismatic leader able to attract the attention of his followers with a magnetic effect on them, unite them with a common idea and lead to achieving goals and objectives. If we look at the history of leadership, then we see that the overwhelming majority of strategic leaders had a strong charisma, which allowed them to inspire and motivate their supporters and followers. A brilliant example is the extraordinary charisma of Sir Winston Churchill, one of the strongest strategic leaders in world history, which helped him unite and lead all the people of Great Britain in the struggle for survival against the external threat in 1940. His ability to inspire people to fight and his impeccable personal reputation put Churchill in the front ranks of the most influential and respected global strategic leaders. Furthermore, beyond doubt, a strong strategic leader must be a deeply honest person and champion of values with such attributes as integrity, which inspires the deep trust of his colleagues and followers. The most serious risk for such a leader, whose consequences are almost impossible to compensate for, is the risk of a ruined reputation.

During the tenth and last stage, the intermediate results are evaluated and the strategy is adjusted (if necessary) during all stages of its creation and practical implementation. At the same time, it should be clearly understood that the results of strategy implementation are not the end result and need to be adapted to the implementation of other strategies or the formation of a new one taking into account the constant process of new circumstances and changes in the environment.

The defined algorithm for developing an HRM strategy throughout the capabilities-based planning process is indicative of and subject to further development and improvement. Further, it should be highlighted that some of the distinctive features and characteristics of the strategic leader (their specific qualities, capabilities, and behaviors) are necessary during the practical implementation of each of the above stages. For example, the qualities of self-criticism, the knowledge of personal strengths and weaknesses, and the ability to use their strengths and compensate for weaknesses are critical, especially as it applies to the rational selection of personnel. Among the strategic leaders’ capabilities necessary for practical application at all designated stages, the following can be emphasized. First is the acknowledgment and awareness of human limitations, including their own; second is the ability to have a natural respect for colleagues and subordinates, as well as a desire to consult, develop, and mentor them; and finally, the ability to recognize the benefits of collaborative working and collective decision-making. Additionally, several types of necessary behaviors, such as a habit of building, leading and listening to teams, as well as a personal ability to work and act collegiately with allies when necessary, can be outlined.[24]

Conclusions

Given the positions mentioned in this article, it can be argued that strategic leadership plays a key role in a human resource management’s strategy development process with the main strategic leader’s qualities, capabilities, and behaviors. In this sense, the strategic leaders’ ability to formulate, make, coordinate, and implement the strategy as a consistent combination of end-state, strategic goals, consistent actions, and resources to achieve them (interrelated combination of ends, ways, and means) is of highest importance for defense institutional capacity building. It is a particularly vital point throughout capability-based planning to provide for qualified, patriotic, and motivated military personnel in the face of contemporary threats and risks in the long perspective within constrained resources. Examination of the possible order of the human resource management’s strategy highlighted that the attributes of a strategic leader are necessary at each stage of the strategy formation, development and implementation.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

Acknowledgment

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Vol. 21, 2022, is supported by the United States government.

About the Authors

Ms. Olena Holota is Head of the Research Laboratory of the Financial Support Problems at the National Defense University of Ukraine. Ms. Olena Holota has a Ph.D. degree in the economic sciences; she is an associate professor in the Economics and Finance Department. She is a Colonel retired with 25 years of military experience and has been serving in the Ukrainian Army Reserve since 2020. During her military service, she occupied the positions of Chief of Regiment’s Financial Service, auditor of the financial and economic department, leading researcher, and head of the Building Integrity Training and Educational Center of “Ivan Chernyakhovskyi” National Defense University of Ukraine. In addition, Olena has completed international training courses on resource and risk management in the military, including the International Defense Management Course at the Defense Management Institute, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, USA. The author of over 50 published articles and studies on the financial provision of social services, state financial control, national defense procurement, acquisition, and corruption risk mitigation.

Colonel Oleksandr Tytkovskyi is with the Personnel Policy Department of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. He graduated from the Royal College of Defence Studies and the Kings College of London with a Master of Arts degree in International Security and Strategy. Mr. Tytkovskyi has more than 30 years of experience in the Armed Forces of Ukraine in positions related to budgeting and resource management, as well as to internal audit of critical areas of military activity as Head of Territorial Administration of Internal Audit of Military Units directly subordinated to the Ministry of Defence and the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. In addition, he participated in peacekeeping operations and the anti-terrorist operation in eastern Ukraine.

73z2.html.