Introduction

NATO and its member countries have been emphasizing the importance of developing and maintaining strategic narratives for nearly a decade on the grounds that activities in the narrative battlefield impact outcomes on the physical battlefield.[1] Lending coherence to the who, what, where, how, and why of foreign and military policies and actions, narratives influence how policies and actions are perceived by adversarial and allied strategic actors, along with the audiences from which these actors draw consent, support, and recruits.[2]

Narrative competition has heightened over the past two decades due to the dawn of social media and the breakdown of shared consensus-forming institutions.[3] Nowadays, amidst every event or situation, humans around the globe find themselves amidst narrative cacophony as different actors and groups “narrate” events or situations. Amidst this melee of discourse, those without firsthand knowledge become the target of narrative competition by other actors and groups—most of whom do not have firsthand knowledge either—making the case that the event or situation matches certain pre-set master narratives about how the world works, along with certain topic narratives about different actors and issues at play. Narrative competitiveness in this context amounts to the ability to create linkages between pieces of information more compelling that serve the purpose of advancing narratives for strategic benefit.

While some participants in narrative competition believe in the linkages they assert, narrative competitions can and often are co-opted by hostile actors attempting to spread and amplify certain interpretations of events purely because these play to their interests. Such actors exploit the associations created by narratives as influential psychological heuristics that reduce the individual ability and will to orient themselves cognitively. Essentially, they use stories to promote a feeling among individuals that they instantly understand events and contexts without having to research their unique features. Narrative deployed in this way has been called “adversarial narrative,” or “narrative warfare” when conducted by organized or state interests against other states.[4] States and other organized entities conduct narrative warfare through black operations deploying fictionalized or decontextualized stories, fake accounts, bot networks to heighten the predominance of a desired narrative, and trolls to intimidate and ultimately silence actors advancing competing narratives.[5]

Though narrative warfare has powerful political and military effects on populations, democratic militaries have been hampered by valid norms as well as legacy structures from developing narrative warfare competencies relative to autocratic states and militaries. As fictionalizing events and inventing fake actors and media sources to disseminate the spurious accounts of them is, and should be, ethically off the table for democracies—at least in most cases—the outstanding question remains, what can democratic militaries do to compete effectively and legitimately in the high stakes narrative battlefield?

Building Resilience to Narrative Manipulation

Clearly, the best-case scenario is for democratic governments to build resilience among audiences to disinformation and other forms of narrative manipulation. Education about disinformation and instilling wider media literacy is an important facet of citizenship that militaries, along with other governmental agencies, should encourage both domestically and internationally. Numerous resources have been developed to assist in this regard.[6] However, given the intense psychological power and emotional appeal of stories and narratives, educating the public to recognize adversarial narrative practices and motivating them to resist their influence is likely to achieve slow—possibly generational—gains at best.[7] Accordingly, the authors believe militaries need to investigate and refine other means of enhancing their competitiveness in the narrative environment.

Enhancing Narrative Competitiveness

A fundamental improvement militaries could make that would give them greater effectiveness in narrative competition would be to cultivate their ability to tell their stories in more impactful ways. Many military actions and activities have inherent features that could permit them to be turned into appealing stories, including high dramatic and value-driven stakes, exotic settings, and often also brave or ingenious individuals. However, military organizations neglect to emphasize these features of their activities in their communications. Understandably, they maintain an objective and impersonal style of information delivery to foster a sense of transparency and avoid imputations of propaganda.[8],[9]

Yet research suggests institutional trustworthiness is also grounded in other values such as benevolence and integrity, which may be easier to communicate through more emotive communicative approaches.[10] Further, purely neutral styles of communication are unlikely to stand out in the narrative melee of social media, leaving a vacuum for other, less principled actors to take up influential roles.

In short, if militaries want their accounts of events to take up more role in the social media landscape of narratives and assume higher levels of trustworthiness among audiences, they may need to update their communication approach. One proposed way to do so is to re-envision themselves from being sources of information, sending out fact-based messaging for consumption by rational actors, to storytellers supplying stories that can appeal on different levels to different types of audiences.[11]

Narrative Intelligence

The first requirement for developing more impactive narratives is to develop a narrative intelligence capability. Stories do not exist in a vacuum; one can enter into, update, and adapt stories selected amongst larger webs, thus changing cultural discourses and minds along the way. Accordingly, a distinctly narrative intelligence would be oriented to identifying and understanding the types of narrative already favored by key audiences, along with stories on military-relevant themes circulating at any given time among those audiences. Narrative intelligence is a close cousin of the cultural intelligence militaries have long been called on to assemble to win the “hearts and minds” of audiences [12] and would help ensure stories told by militaries have a chance of resonating with audience concerns, interests, and tastes.

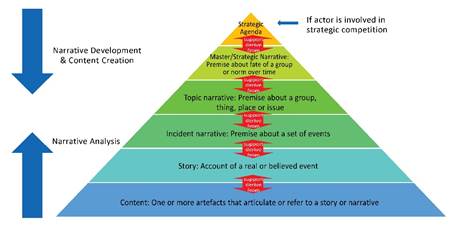

The good news is that AI-driven tools are in development that will be able to detect and cluster narratives on traditional and social media according to common threads amongst them, along with sentiments they feature and the social networks they are popular amongst.[13] By structuring the big data of the public information environment, such tools can help militaries makes sense of narrative-lay-of-the-land and how they can effectively engage in it.[14] We propose using a pyramid-like narrative model for processing data on stories circulating among groups to facilitate a broader understanding of the narratives they favor on various topics and underlying master narratives that structure their perspectives.

Figure 1: Narrative Analysis and Design Model.

Narrative Design

The narrative model can also help curate and design content that can speak to—and sometimes nudge—audience perspectives in ways that can create common ground. The hardest part of communicating via narrative is designing content that will meaningfully convey favored narratives to specific real audiences. Narratives take the form of claims either about topics (“vaccines are more harmful than the diseases they prevent”) or events (“COVID-19 was made in a lab”). Audiences are typically induced to adopt narratives not by logically encountering them in the form of claims but by repeatedly encountering stories that testify to them, e.g., testimonies of people getting sick from vaccines or supposed witness accounts of cover-ups at the imputed laboratory. The most effective narrative communicators thus primarily message not narratives in themselves but stories and actions that testify to the validity of those narratives.

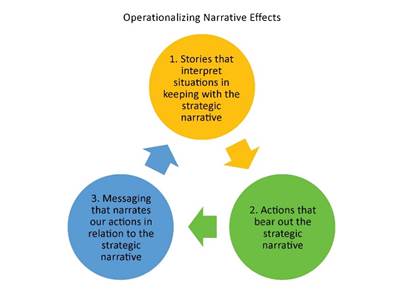

Given that many militaries are already committed to the idea of strategic narrative, they are in an excellent position to excel at this type of narrative communication if they have the will and skills to do so. It is a Strategic Communications commonplace that military operations should be guided and justified through the use of strategic narrative.[15] Yet militaries need to put much more thought into how strategic narratives can be effectively communicated to audiences through telling and enacting stories that would make these narratives meaningful and convincing. We propose three main interconnected vehicles for militaries to achieve narrative effects, namely (1) by telling stories about relevant situations that interpret them via narratives; (2) by initiating actions that bear out narratives; and (3) by initiating messaging about their actions that narrates how these actions are congruous with them.

Figure 2: The Three Modes of Operationalizing Narrative Effects.

A narrative-driven strategy or operation should be designed to cycle seamlessly among these vehicles as it uses its communication capabilities to provide stories to audiences demonstrating what it sees is happening along with the solution it has identified, faithfully embodying that solution in kinetic and other types of action, and then using additional detailed stories to explain to audiences how those actions created the desired results.

Moving on to how to craft the stories that are a key part of this cycle, theorists of storytelling (‘narratology’) tell us that impactive stories are not simply accounts of events.[16] Rather, good stories demonstrate at least four features, abbreviated as PAIV: Plot locating the phase of the narrative in play and anticipating where it is going—are we in the calm before the storm or the darkness before the dawn; Archetypes consisting of formulaic and structurally opposed characters involved in the action; Imagery that makes situations tangible to audiences; and Values being tangibly reinforced or defended. The good news is that military stories tend to be dramatic with high-value stakes and inherently offer a range of PAIV features. Still, storytelling and story-crafting are needed to bring these features out more strongly by turning military events into gripping stories with compelling characters and natural plots with ups and downs and twists and turns.

When not involved directly in action, good plotting means moving beyond the static representations of military gear that so often predominate in military social media. Instead, military messaging should continuously locate where they see themselves in the larger “plot” of their strategic agendas. How are service members protecting or advancing what is valued, on behalf of whom, and to what end? Literary theory tells us that two core plots that underpin action are comedies and romances or, respectively, preservation of a basically good condition despite bumps and transformation of a basically bad condition into a good one through radical purging.[17] The type of operations a military is engaged in can be compellingly communicated by drawing on the formulaic features of these types of plots. Comedies, for their part, tend to employ relatable characters, clever teams and schemes, and humiliating dismissals of ill-doers, whereas romances tend to feature more ambivalent heroes, uncertain and perilous quests and encounters, and dramatic and violent reversals.

Stories also need characters, which could be more determinately created with text and images showing individual commanders and force members as archetypal figures engaged in compelling military actions for meaningful purposes. Individually naming these featured members is optional but would be helpful for attracting the kinds of “parasocial relationships” among audience members and key to sparking their involvement and loyalty.[18] As discussed, especially relatable or attractive individuals make excellent comic heroes, whereas exceptionally perseverant or intellectual members stand out as romantic figures. Casting negative archetypes is likely to be a stickier point, as there is understandable political reticence about naming villains in under-the-threshold circumstances. Still, for the purpose of creating drama, the presence of threatening actors justifying military actions should be hinted at, at the very least.

All these characteristics are illustrated in the following picture, aptly found in the “Great Military Pics” Twitter handle. This picture implicitly encapsulates P-plot of menace being held off, A-archetype of a protector defending innocents, I-imagery of munitions being used to hold the line “between a rock and a hard place,” and V-values of security and freedom from terror. While not every military tweet can be this dramatic, this one offers an example of the kind of in media res action and evocative contrasts to which military storytelling should aspire.

Figure 3: Posting by “Great Military Pics” Twitter account, 2013 (source unknown).

Case: Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

As the above picture suggests, the best storytelling in the political-military milieu comes from making the most of circumstances that arise by broadcasting exciting as well as relatable events, demonstrating how these events are connected to the values, and giving platforms to interesting and evocative real-life individuals with the potential of emerging as characters capable of drawing audiences into causes.

A contemporary example of a captivating and high-stakes political story with strong characterization and plot was that of Belarusian leader-in-exile Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. In 2020, Tsikhanouskaya ran for President “out of love”—after her husband was arrested for planning to do so—to free him from prison. Losing the official vote, Tsikhanouskaya fled to Lithuania to rally support as Belarus’s legitimate leader-in-exile. She was taken on as a cause celebre by European and allied circles, perhaps in part because her story revived a classic comedic (which is not the same as funny) plot structure going back to the Roman period, in which courageous young people struggle against decadent old tyrants to build a world in which they can love freely.

Figure 4: Tweet of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, August 7.

This story also demonstrates how impactive stories are fuelled by the actions of classic characters – that is, of “archetypes.” The attractive Tsikhanouskaya plays her part well as a relatable, enterprising comic heroine, expressing herself on social media using plain, emotive, value-driven language. In contrast, the incumbent President Lukashenko is easy to peg as a corrupt but blundering tyrant, yet another archetypal character of Roman comedy.[19]

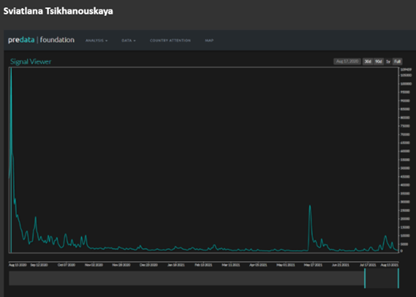

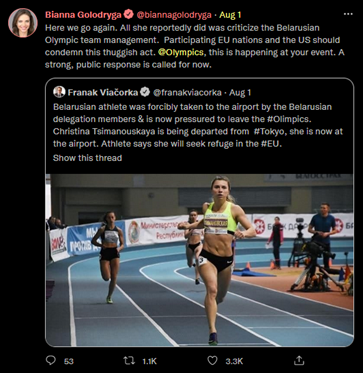

True to form, a review of the social media data suggests that most of the drama in the story has been generated through absurd overreaches by the Lukashenko government. These included bringing down an international jet to arrest yet another young activist couple and having Olympics coaches pressures a female sprinter to return home to face consequences for social media candour, leading to her defection at the airport where she cleverly employed Telegram and Google Translate. Social media data also shows that these actions did not purely speak entirely for themselves, but were ably amplified by Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s campaign team to reach international notoriety.

Figure 5: Search Results from Predata Platform Showing Attention to Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya Peaking in 2021, the Day the Lukashenko Regime Brought Down RyanAir Flight 4978.

While we cannot be sure if affairs in Belarus will achieve the traditional comic outcome—an inclusive society where young people can love freely [20]—the story is being skilfully told to make important strategic audiences around the world pull for that ending.

Conclusion

Enhancing narrative competence will require militaries to advance several interconnected capabilities. These include expertise in curating and communicating stories that incorporate a plot, characterization, and imagery and delivering through natural voices along communication paths that will encourage organic spread through key audiences.

These capabilities also include OSINT and analytic capabilities for understanding the narrative cultures of audiences in the information environment, including master narratives, favored plots, and characteristic stories that express their worldviews and aspirations. As an example, comedies such as the one being performed by Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya tend to be favored by optimistic progressives who believe problems might solve themselves if only vested interests were cleared away. Another example of such an optimistic, progressive leader is Greta Thunberg, the young environmentalist who advocates for reduced influence by fossil fuel companies to facilitate wind and solar power development. Not coincidentally, Thunberg attended a rally for Tsikhanouskaya last May in Sweden – thereby spreading the cause of Belarusian resistance among her own networks. Militaries and other institutions could learn well how to harness sympathetic influencers in such an effective way.

Figure 6: Tweet of CNN Journalist Bianna Golodryga Retweeting Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s Senior Advisor on the Belarusian Regime’s Mistreatment of Olympics Sprinter Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, August 1, 2021.

Narrative competence should also provide means to understand adversarial narratives and anticipate the inferences they may draw. In contrast with relatively light-hearted comic narratives preferred by optimists, alienated communities and individuals—the likes of revolutionaries as well as conspiracists—tend to be drawn to darker romance narratives of ambivalent heroes determined to enter “the belly of the beast” of elite power and slay their ways out.[21] One can find such violent romance narratives at the basis of many of the darker political fantasies around us occasionally acted out in the real world. Moreover—as the Predata results above show—one’s own side’s actions can be the biggest amplifiers of one’s adversaries’ narratives. To avoid playing into adversarial romances of ordinary folks standing up to corrupt elites, militaries and other institutions might consider spurning common bureaucratic photo ops of leaders in handshaking events and boardrooms. Instead, such institutions would do better to focus narrative attention on everyday heroes inside and outside their organizations who evince values of sincerity and benevolence, which are essential for building trust.[22]

But the narrative understanding that most needs to be internalized among military institutions is how the force as a whole is implicated in storytelling. Commanders who design operations need to understand that, increasingly, the stories that spread about their actions will impact far more people than the platforms or weaponry wielded in them. Operators need to understand that cracks in their operational narrative will inevitably be exploited by adversaries. Communicators need to understand that a keen plot, relatable characters, and plain language appeal to everyone. In contrast, postings featuring primarily gear and jargon speak to almost nobody beyond the institution itself, reinforcing cultural silos rather than paving paths beyond them for military values to be advanced. In the old-is-new era of narrative, no one is off the hook from telling stories – or from knowing the stories they are enabling others to tell about them.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

Acknowledgment

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Vol. 21, 2022, is supported by the United States government.

About the Authors

Suzanne Waldman is a Defence Scientist at Defence Research and Development Canada.

E-mail: suzanne.waldman@ecn.forces.gc.ca

Sean Havel is a co-op student at Defence Research and Development Canada.

E-mail: sean.havel@ecn.forces.gc.ca

News: Preliminary Insights from a Systematic Review,” in Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference Cognition and Exploratory Learning in the Digital Age 2020, ed. Demetrios G. Sampson, Dirk Ifenthaler and Pedro Isaías (Lisbon, November 2020), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344217167_Educational_approaches_to_address_fake_news_preliminary_insights_from_a_systematic_review.