Thorsten Hochwald *

Introduction

General

To look at social media in the context of conflict seems, at first glance, a stretch of the imagination. Before 2011, many would have argued that the Web 2.0 or social media was originally designed for business purposes and had little to do with conflict at all. However, following recent events, mainly in the Arab world, this view faces some serious challenges. Some would go so far as to claim that new media can be and actually have been “weaponized” in order to catalyze the transformation of existing authoritarian regimes in the Arab world. It has also been argued that social media was the single most important factor in bringing about the Arab Spring – leading to it being referred to as “Revolution 2.0.” [1] Those who support the antithesis to this argument merely see social media as a set of new information exchange tools made available by the ever-advancing tide of technology. Whatever the truth may be, the events in the course of the Arab Spring, which swept the Region of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) since December 2010, took many by surprise.

As these events are quite recent or still ongoing, factual data is fragmentary, and research on the connections between conflict and social media is incomplete at best. Although numerous books have been published, up-to-date information can be found mostly in think-tank research papers and articles on the Web. Much is still unresolved and in a state of change. Moreover, the nature of conflicts has changed after the end of the Cold War, from mainly inter-state to intra-state. Civil society’s influence became a major and expanding factor within the conflict sphere. Last but not least, the nature and number of actors playing important roles in these struggles have also changed—not only in dimension but also in their scope of action.

Whereas the actual impact of these actors is still being debated, the rather new phenomenon of social media in the sphere of civil society seems to have played a role in all of the recent struggles, and has therefore garnered substantial media attention in itself. In a way, social media appear to make support for authoritarian regimes more costly,[2] while simultaneously acting as influencing factors causing a considerable shift in the balance of power within conflicts. The literature that examines the impact of social media in sub-national conflicts other than war is very undeveloped. The majority of earlier works emphasized that social media enhance the political power of the people. However, the most recent studies note that governments are becoming highly adaptable, and are beginning to use social media to their advantage. This article explores the impact social media will have on governments’ security policy and the reshaping of security instruments in order to cope with this new development. The questions that arise are therefore the following: How significant will this impact be, and how can governments employ these tools in order to avert, constrain, or completely remove the threats to their existence, and thereby help safeguard national strategic interests?

In this context, this essay will try to shed light on how social media have been used by state and non-state actors inside (mostly) authoritarian regimes experiencing intra-state conflict, such as the Arab revolutions, and what impact social media have had on these events. It will look at the topic from different perspectives and try to establish whether social media are a curse or a blessing for governments, and which side actually reaps the benefits of social media’s impact in the conflict sphere. In the process, it will address the question of whether there actually has been a shift in balance from revolutionaries towards the government. Subsequently, the article will extract some patterns and try to apply them to a democratic context, assess the potential impact on future security policies, and attempt to formulate certain policy recommendations that would enable governments to adapt to this new dimension of the conflict spectrum.

Methodology

This article aims to present a current picture of social media and their use by groups and organizations at both the state and non-state level in the conflict spectrum and analyze their present and future influence on security policy. By taking into account different assessments of social media’s role and by studying the way social media have been used during intra-state conflicts, such as the Arab revolutions, this paper will try to analyze whether social media play an important part in intra-state conflict and what this role actually looks like. Subsequently, some patterns shall be extracted and tested in a democratic model context. The article will conclude with certain policy recommendations for security policy makers on means to implement the use of social media in pursuit of their national interests.

The first part will provide the theoretical framework for the paper by defining the two main concepts: social media and conflict. This will offer a general understanding of the context of the analysis as well as the author’s perspective. Following a definition of social media, the essay will outline a brief history of how social media came into existence, and developed from one-to-many (radio, newspaper, etc.) modes of communication towards many-to-many (social media) modes of information distribution. The article will then address the different types of media and their respective reaches within society, subsequently looking at the implications of each – what it can and cannot achieve as a tool or actor. Furthermore, the paper tries to see whether social media have different impacts on governments and the public.

Using an analytical approach, the article will look at selected case studies from the Arab Spring to establish the strengths and weaknesses of social media, the role they play in intra-state conflicts (with special reference to authoritarian regimes), their impact, and how government’s reactions have either reduced or intensified this impact. It will do so by analyzing a variety of open-source documents from organizations, research institutes, and think tanks as well as publications from the Web and relevant books. It will consider opinions on social media not only from Western academics but also some Arab bloggers, participants in the Arab Spring, or academics from the region in order to determine if the perception of social media’s role is the same in the different regions.

Having established the strengths and weaknesses of social media and their potential influence on all actors involved in a conflict as well as in conflict prevention, the article will assess their effect on politics, especially security policies and further likely actions of governments adapting to the influence of social media, before concluding with a look towards the future.

Definitions

The article will lay the foundations and begin with a definition of social media valid for the scope of this paper. This is required due to the fact that, although social media are not actually new, they are still rapidly evolving and have only recently (the last five to seven years) entered the mainstream of civil society. And they have shown staggering growth rates: “the number of active social media users surpassed the first billion in 2011, many of whom connect to social media using their mobile devices.” [3] And more is still to come; experts “expect the total number of worldwide Social Networking accounts, including both Consumer and Enterprise accounts, to grow from about 2.4 billion in 2011, to about 3.9 billion in 2015. The number of Social Networking users is expected to rise from 798 million users in 2011, to over 1.2 billion in 2015. (Note: users typically have more than 1 account).” [4] With these high rates of growth and steady change, it is not surprising that research about the impact of social media on society is still in its infancy.

Academia, government agencies, and ordinary people all have different views on social media and experience them from divergent perspectives. Therefore, a commonly agreed upon definition is still missing. There are numerous definitions around, which mostly are flawed in that they fail to provide insight into both the means and purpose of social media, which for this paper are both relevant in order to identify its implications for policies later on. Hence, to achieve a more complete definition the essay will further build on two perspectives on what social media entails. First, the definition provided in a research paper from the Governance and Social Development Resource Centre at the University of Birmingham, reads as follows:

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

World Social Networking Accounts (M) | 2,395 | 2,723 | 3,073 | 3,471 | 3,890 |

% Change |

| 14% | 13% | 13% | 12% |

World Social Networking Users (M) | 798 | 910 | 1,030 | 1,135 | 1,240 |

% Change |

| 14% | 13% | 10% | 9% |

Average Accounts per User | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

Figure 1: Worldwide Social Networking Accounts and Users, 2010–2015.

Source: Social Networking Market 2011-2015, The Radicati Group, Inc.

Such technologies allow for the mass distribution of a one-way message from one-to-many. The widespread diffusion of the Internet, mobile communication, digital media and a variety of social software tools throughout the world has transformed the communication system into interactive horizontal networks that connect the local and global. New forms of social media, such as SMS, blogs, social networking sites, podcasts and wikis, cater to the flow of messages from many-to-many. They have provided alternative mediums for citizen communication and participatory journalism.[5]

The second attempt in defining social media is provided by an analyst of the U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS), who provided the following definition:

The term Social Media refers to Internet based applications that enable people to communicate and share resources and information. Some examples of social media include blogs, discussion forums, chat rooms, wikis, YouTube channels, LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. Social Media can be accessed by computer, smart and cellular phones, and mobile phone text messaging (SMS).[6]

This gives more insight into means and purpose of social media, but for the purposes of this article it is still not conclusive enough. Therefore, a fusion of the combined definitions will be used here:

The term social media refers to applications that enable people to communicate and share resources and information and allow for the mass distribution of a one-way message from one-to-many, thereby transforming the communication system into interactive horizontal networks that connect the local and global. The new forms of social media, such as SMS, blogs, social networking sites, podcasts, and wikis, cater to the flow of messages from many-to-many and provide alternative mediums for citizen communication and participatory journalism, allowing distributors and recipients of information simultaneously to use and create content.

Following this definition, there is a clear difference between social media on the one hand and new media, including satellite television (Sat-TV), on the other. As there is only a modest possibility of active interaction, Sat-TV shall, for the purpose of this study, be treated as a one-to-many broadcasting medium, where broadcasters such as Al-Jazeera are just distributing information by means of a new technology to a broader audience. And although analysts agree that Al-Jazeera did also play an important role in the Arab Spring, due to the editorial scope, this article will not address this topic.

The term “conflict” is hard to define, due to the many different and in some cases even opposing explanations of what it entails. This paper will omit looking at conflict as war between states or government-like entities already fully engaged in combat activities. In accordance with the title, this paper will look at intra-state conflict other than war. For the scope of this paper, conflict is defined as “the most common type of conflict that occurs between the armed forces of the government and an opposing civil organized group within the state borders. These conflicts are often driven by ethnic, religious or ideological incompatible positions.” [7] Here the paper looks at the “‘classical’ intra-state conflict without foreign intervention.” [8] Having provided sufficient theoretical basis for the analysis, the next section of the article will provide a brief look at the history and the different relevant types of social media before considering what implications they will have for society.

Social Media

History, From Telecommunications to Web-Based Interaction

Vast changes have occurred on the communication landscape during the last three decades, in a way that can be better described as revolutionary instead of evolutionary. Pre-Internet mass-communication systems relied mainly on mass media, such as radio, television, and print. Although it can be argued that social media are not actually new—as people have utilized digital media for information acquisition, social interaction, and networking for more than three decades—it has only recently entered the mainstream of civil society. This “new” form of communication has entered everyday life, and has changed it profoundly.

These forms of interaction, however, did not begin with the personal computer era – they started with the telephone. In the 1950s, hackers began rogue exploration of telephone networks via “phone phreaking,” a method designed to make use of telephone companies’ test lines to host virtual discussions, circumventing the tremendous charges to the detriment of the phone companies.[9] The first real “blogs” thus took place on hacked company voice-mail systems until they were discovered and terminated. This was followed by the development of the first Bulletin Board Systems in 1979, which were basically small servers connected via a phone modem, hosting social discussions on open message boards, online games and more. These techniques, however, were mainly used by distinct “underground” users, who were active in hacking, information gathering, and illegal file sharing. At the same time, commercial online services like Prodigy and CompuServe appeared in the 1980s for “social” interactive practice for the general population. The first chat systems were launched, although at staggering cost (USD 30/hour).[10]

During the 1980s, costs gradually decreased as accessibility increased. Nevertheless, the real breakthrough did not come until the 1990s, with the public availability of the Internet, or World Wide Web. Although the Internet already existed since the late 1960s as a network, it became available exclusively for universities, governments and, via illegal access, the hacker community in 1991.[11] This changed around the mid-1990s with the introduction of private Internet Service Providers (ISPs), which subsequently spread around the world and provided the possibility of advanced communication forms for the general public. Many new possibilities were invented to share, communicate, and participate in the entire news spectrum. In addition to peer-to-peer file sharing applications and instant messaging services, social networking and social news websites began to appear.

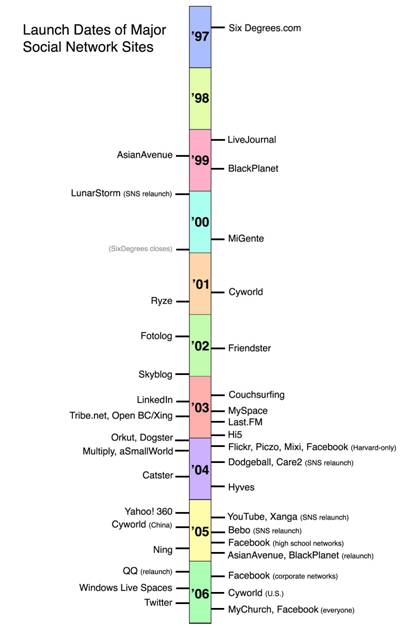

In contrast to the aforementioned “sharing sites,” which basically allow connections with strangers, networking sites operate on the principle of profiles and networking initiation. Although contact between strangers is basically possible, the distinctive feature of networking sites is the ability to “enable users to articulate and make visible their social networks. This can result in connections between individuals that would not otherwise be made, but that is often not the goal.” [12] More importantly, “interactions commonly are multi-directional, interactive, and iterative. An online newspaper reader can comment, and the author can respond. What previously seemed like insurmountable barriers between writers and other public persons have to a large extent melted away, inherently connecting people and information in spontaneous, interactive ways.” [13] The new technology gradually entered people’s daily life, especially with the younger generation; it completely changed people’s interaction with each other, as well as the manner in which they shared and gathered news and information. The first of those social networking sites (see Figure 2), which started the so-called Web 2.0 phenomenon, was SixDegrees in 1997, followed by the development of Friendster (2003) and MySpace (2004). The launch of Facebook in 2004–05 finally initiated a real social network boom. An additional trend was established with the emerging social news websites, basically using editor-picked stories, shared bookmarks, and comments on mostly static pages.[14]

The missing link to real global networking, especially in countries with a lack of landline bandwidth and static computers, was finally provided by the development of the iPhone and its functional mobile Web browser. This innovative technology allowed location-based social networking and real-time news updates. It created the opportunity to make use of social media independently, even in areas with only mobile communications as means of access to the Web.

The large—now global—community of users and the low barriers of entry presented by the software enable people everywhere to connect with all forms of social media like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and the various forms of blogs. This has in turn made an almost global social network possible, formed on an ad-hoc basis, thereby giving it enormous potential to rapidly share news, thoughts, and ideas within the network. Combined, these media have enormous power to shape events, both due to the numbers of users and to the possibilities of its combined software potential. It is making “communication on the Internet … no longer a controlled, organized, exclusive, product-driven monologue; it is an authentic, transparent, inclusive, user-driven dialogue” with global reach.[15]

This consequently has far-reaching implications for governments, politics, and policies, and thereby for the everyday life of people. Although consequences in conflict-prone states are more apparent, these media have the potential to affect society anywhere. The question of how social media can influence everyday politics, both as a tool and an actor, is a key concern of this article.

Implications for Society

Interaction, global proliferation, and the increasing interpenetration of society enable social media to have extensive implications. Whereas social media in the beginning first and foremost spread in the developed world, as they required the availability of computer technology and transmission bandwidth, the shift towards mobile technology made global propagation possible. Social media have developed relatively unimpeded by national legislation due to their origins in countries with constitutional rights for freedom of speech and communication. With mobile technology in developing countries increasingly becoming the standard communication method, the possibility of access via smart phones provided the opportunity for social media to expand globally. This means that social media have also arrived in less developed, often non-democratic, authoritar ian countries. Social media affect all these societies differently, not always in a beneficial way to either people or governments.

Figure 2: Launch Dates of Major Social Network Sites.

Source: Boyd and Ellison, “Social Network Sites.”

Obviously, the very use of social media as an instrument for information transfer can be detrimental to a state’s security. It can be argued that the higher the degree to which a society is dependent on the use of information technology (IT) and a correspondingly high ratio of online information acquisition, sharing, and control, the higher the vulnerability of this society to Web-based threats.[16] Accordingly, the risks of incorporating social media applications in the day-to-day running of a country, either in strategically important companies or in government agencies, seems at first glance higher for more developed countries.

However, there are less obvious but still essential areas that are affected by social media, two of which are of major importance. First, secrets are very difficult (if not impossible) to keep. Smartphone technology allows numerous possibilities for users to interact, transfer, and obtain digital information. Additionally, mobile phone cameras can be found almost everywhere in the field – wherever there are people, there are cameras. This makes it almost impossible to cover up events. Second, social media provide a platform for civil society to influence the public sphere, where civil society is understood as the organized expression of the values and interests of society.[17]

The public sphere—“a network for communicating information and points of view”—is exactly the area where social media have brought about a dramatic shift.[18] Previously, depending on mostly government-controlled, one-to-many media for information access, a government’s interaction with its citizens was predominantly reduced to election periods. Nowadays, civil society can easily gather information, access structure, and channel debates as well as share ideas and thereby express its support or rejection of government policies anytime and from anywhere. It would not be too far-fetched to call this a new public sphere, situated in the online domain.

Those two main characteristics generate several implications for both governments and society. As social media and the incorporated technology provide a stage for public society, decisions of governments are almost instantaneously brought under the scrutiny of public opinion. In order to win public support, the need for transparent decision-making is increased, and dubious back-room deals are less likely to pass public scrutiny. Due to the continuous supervision of politics, the reaction time for governments (compared to the pre-social media era) has been dramatically reduced. Additionally, in democracies politicians seem to become less risk-prone and more cautious and anxious when making decisions, as mistakes are quickly made public. Especially in times of crisis, this is not always a good approach to leadership.[19]

On the other hand, one needs to evaluate whether governments can utilize social media to their advantage. It can be argued that, if social media are utilized and exploited properly by government agencies, they could “unlock self-organizing capabilities within the government, promote networking and collaboration with groups outside the government, speed decision-making, and increase agility and adaptability. … It could also decrease the probability of being shocked, surprised, or outmaneuvered.” [20] In this way social media could act in a positive way as a warning and prevention tool and, if used appropriately, as a manipulation device to prevent violence. Hence, by considering the above implications, this article argues that social media in one way or another affect the whole of society.

Social Media and Intra-State Conflict

The connection between conflict and traditional media has been subject to much research. In the context of researching the respective relations to social media, it has been argued “that the complex relationship between media and conflict is longstanding. Traditional mass media have been used to amplify and extend viewpoints and ideologies, to persuade audiences at home, and to influence opposing sides in conflict. However, both media and conflict have changed markedly in recent years. Many twenty-first-century wars (conflicts) are not only about holding territory, but about gaining public support and achieving legal status in the international arena.” [21]

The link between governments and information is even more important when it comes to authoritarian regimes, because they have a tendency to regulate the distribution and availability of information via control of the media. Such regimes frequently aim at exerting power over their subjects not only through force but also by building up a monopoly on information and influencing the public with the careful dissemination of pro-government information.

This was already true before the Internet age, but since then not only technology has changed, but so have the characteristics of conflict itself. Conflict before the end of the Cold War mainly consisted of wars between sovereign states. Since the collapse of the bipolar world order, one can observe a shift towards intra-state conflicts of various intensities. In intra-state conflicts, social media have created a new relationship between governments, politics, and its subjects. The new civil society has become a powerful actor in the “struggle” for public opinion, and is often a crucial factor in the quest for international attention and support.

Accordingly, “media are increasingly essential elements of conflict, rather than just a functional tool for those fighting. Acts of violence performed in the theatre of the public eye can be used in the fight for influence. Violent groups increasingly use media to achieve their goals, and violence itself is also used as a message.” [22] Many researchers argue that social media in future conflicts will reverse the lack of accessible and reliable information in previous wars to a state of information saturation, creating an over-supply of data. Thus, information itself becomes the center of attention, even more than traditional military power. Therefore social media provide civil society with a tool that equalizes the area of previous governments’ supremacy: information dominance.

However, the dependence of both parties on the Web-based information domain has its own strengths and weaknesses. Protest movements’ reliance on social media allows regimes to effectively monitor and influence online content. This may lure potential protesters away from certain hotspots, or lead them to areas of less concern, effectively reducing the protest movement’s impact. Another method is by asking Facebook or Twitter to stop certain pages from being published or, more crudely, as in Egypt in 2011, simply shutting down the country’s Internet services.[23]

The recent revolutions have shown that the rapidly changing and developing technologies and characteristics of social media have become a challenge to which regimes need to adapt quickly. There is little doubt that “new media technologies have increased communication and information dissemination in the context of conflict.” [24]

The much-coveted prize in the conflict between protest movements and (authoritarian) regimes seems increasingly to be national and international public opinion. The global nature of the Web enables social media to transgress national borders and gain international attention, which could lead to recognition and support. Therefore, one can argue that there is a definite link between social media and conflict, as the constant presence of social media provides a public stage, which also makes transgression and violence immediately apparent and thereby costly for the government to stop. Controlling media and information flows is an effective tool for governments in order to cover up transgressions, which by its nature is especially important to authoritarian governments, as they depend on the monopoly of available information far more than democracies in order to stay in power.[25]

Social media eliminate this monopoly on information and easily make potentially damaging incidents public. As Ivan Sigal notes, “The ability to communicate, and to produce and receive diverse information through participatory media, is part of a struggle within conflict-prone societies to either allow for non-coercive debates and dialogue that focus on endemic weak-state problems, or equally, enable those seeking power to organize for political influence, recruitment, demonstrations, political violence, and terror.” [26] The opposition can use social media as a coordination tool for demonstrations, to mobilize resistance, and to organize protest movements against government policies. They reduce the formerly high costs for protest groups to recruit, organize, and participate in anti-government actions, making the activation of protest feasible. However, social media on their own are not enough to bring about regime change. They generally require a trigger; the proverbial straw that breaks the camel’s back and exceeds the citizens’ level of acceptance.

The key, then, is to mobilize sufficient support, which “requires organization, funding and mass appeal. Social media no doubt offer advantages in disseminating messages quickly and broadly, but they are also vulnerable to government counter-protest tactics. And while the effectiveness of the tool depends on the quality of a movement’s leadership, a dependence on social media can actually prevent good leadership from developing.” [27] Although social media have been used to organize protests on a tactical and operational level, research has shown that protest movements organized via social media lack the capacity for strategic thinking. Since social media constitute a decentralized network, their mechanisms closely resemble swarm intelligence: effective once in progress, but difficult to focus. This would require the emergence of an accepted, high-quality leadership cadre to direct the movement in the desired direction. Real, non-personalized online leadership is difficult to achieve, and is frequently unable to generate sufficiently dependable loyalty that is able to withstand setbacks. In the end, the aim is to create an alternative form of leadership on the public stage, which finally would require a personal connection. Lacking that, social media are able to encourage and manage civil disobedience to a degree previously unheard of, as long as the government does not obstruct the flow of information.

However, more is required in order to evolve from the stage of activism against regimes into a protest movement that can produce a critical mass of citizens on the street. The question is how to translate the rather faceless and comparatively low-risk activism on the Internet into individual identification and a willingness to accept personal risk on the street protesting against regime authority. This not only requires a socially persuasive nature on behalf of the movement, but also ultimately broad-based support and a legal status for the opposition’s aims.[28] The requirement for “protest organizers is to expand their base beyond Internet users, they must also be able to work around government disruption. … Ingenuity and leadership quickly become more important than social media when facing government counter-protest tactics, which are well developed even in the most closed countries.” [29] In order to be successful, the aim of opposition leadership must therefore be to inspire, gain international attention (as national regime attention is counterproductive), and adapt their methods of operation according to regime responses.

So how does this relate to real world conflicts? How does the use of social media change the course and outcome of disputes? This shall be analyzed through case studies from the recent revolutions in the MENA region in the following section.

Analysis: Social Media – A Tool for Protest?

Underlying Factors for Revolution in the MENA Region

It is commonly agreed that the use of social media has had a significant impact on recent revolutions around the world. As Ivan Sigal writes,

The discord between citizens creating and disseminating media and governments aspiring to restrict, censor, and influence in conflict situations reflects the tension between informal, fast-moving information and community networks and the formal hierarchies of state power. New information networks link people together through non-state, citizen-oriented communities, challenging the concept of a ruling authority able to control and direct information flows amongst its citizens.[30]

However, the new technology displays both advantages and disadvantages. The following section will scrutinize real-world limitations in their use and various impacts throughout the protests in the Middle East and North Africa, commonly grouped together under the rubric of the “Arab Spring.” The first step in this respect shall be an evaluation of the factors underlying these revolutions.

Similar to other great events in world politics, the uprisings in the MENA region started on a local level, expanded regionally, and finally acquired a trans-regional dimension. The uprisings can be classified as historical, with a global impact. Moshe Ma’oz has written, “These popular uprisings have constituted a remarkable historical political phenomenon of the Arab street secular and religious, male and female, casting off the ‘barrier of fear’ against their oppressive, despotic, and corrupt rulers, insisting on obtaining freedom, dignity, justice, equality, and democracy.” [31] The process itself and its aftermath will probably continue longer and potentially be bloodier than the end of the Cold War was for Central and Eastern Europe, and its effects will change the strategic picture of the entire region for years to come.

Several publications rank social media as the most important factor of those playing a role in the twenty-first-century transformations of authoritarian regimes in the MENA region.[32] There are many claims that the “Arab Spring” was only possible through social media, but social media by themselves could not have brought the uprisings to the actual level of anti-regime action without certain underlying factors. Although these differed from country to country, there are also some clear similarities. Generally speaking, the socio-political situations in all of the affected states were ripe for change. Poor governance, blatant violations of human rights, together with a high level of corruption and increasing inequality (with particular discrimination against women) and poor prospects for youths constituted the norm. Most of the authoritarian governments used excessive force against the opposition and had little interest in letting their subjects participate in ruling the country. Additionally, the absence of the rule of law, vast structural problems in economic development, inefficient resource allocation, and high unemployment, especially among youths, gave an edge to the already explosive mixture of factors.

Excessive inflation exacerbated the already high rate of poverty, and the growing number of young (often qualified) people lacking adequate jobs created an entire generation without future prospects. Demography did not help the ruling powers, as exceptionally high birth rates generated a population bulge in the younger generations, providing far more jobseekers than the economy could absorb. This collection of factors became intolerable, but the fear of oppression measures from the regimes kept an increasingly well-educated and informed sector of the population in check. Many analysts were not surprised when the Arab Spring took place in 2011, but rather that it started so late.[33] The only thing lacking was a specific triggering event. Such an event occurred in Tunisia. Spreading news of this triggering event via social media played an important role in getting the revolution started. But what actually was its share in the ongoing events? This will be dealt with in the following sections.

Social Media and the Arab Spring

Tunisia is where the Arab Spring began. A twenty-six-year-old Tunisian street vendor committed suicide by burning himself on 17 December 2010 as a form of protest against the lack of opportunities provided by the regime in Tunisia. His suicidal act was the catalyst that set off a rapidly spreading chain of protests. News of his self-immolation (including images) was quickly disseminated via Facebook, from where it reached satellite TV (mainly Al-Jazeera). Without a mobile phone camera and social media, the burning might have gone unnoticed—as it took place at the same time as the suicides of other desperate people without prospects in the region—but this crucial event was disseminated widely, and set off a chain of events that are still unfolding.[34]

The uprising in Tunisia lasted about a month, and ended with the expulsion of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who had autocratically ruled the country for over twenty-three years. He was quickly driven into exile in Saudi Arabia by an agitated population. In the beginning, the regime applied oppressive measures in order to quell the protest movement. The progressively brutal measures included deliberately targeting protesters. This method was meant to induce fear, but it had the contrary effect. By virtue of the sheer magnitude of violence applied against its own population, the regime quickly lost any remaining support and legitimacy it had retained to that point. Most of the violence was made public via YouTube and subsequently via Al-Jazeera, thereby providing a global stage for the reproduction of images of the unfolding events. Facebook and Twitter played a crucial role in coordinating ad-hoc demonstrations and diverting protest actions around known anti-protest arrangements of the regime. In the end, the loss of support of the well-educated middle class, women, and the younger generation was crucial.[35] These factors were mainly responsible for creating the public platform of civil society via social media, directing the protests and making it clear to the regime that a change of government was now the only remaining option.

The uprising succeeded with the subsequent change of government in Tunisia at the end of 2010, and it rapidly expanded into Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Qatar, Bahrain, and Syria. As a United States Institute of Peace report notes, “An extraordinary wave of popular protest swept the Arab world in 2011. Massive popular mobilization brought down long-ruling leaders in Tunisia and Egypt, helped spark bloody struggles in Bahrain, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, and fundamentally reshaped the nature of politics in the region.” [36] Furthermore, it had an impact on Oman and Jordan as well, without resulting in actual uprisings. But why did the revolutionary tendency spread over the whole MENA region? Under normal circumstances, the effect of a regime change in Tunisia would probably have spread no further, the country being less prominent in terms of power, regional influence, and interdependence. Again, a kind of virtual pan-Arab civil society, mainly fuelled and connected via social media, created the platform for change.

Egypt: High Stakes

The uprisings soon reached Egypt, where the underlying socio-economic conditions were comparable to those in Tunisia (as are, in fact those in many countries in the region). The same population strata—the well-educated youth without future prospects and the shrinking middle class—connected via social media, and satellite TV brought the possibility for change to the suppressed Egyptian civil society. Some researchers even claim that this response created a new political generation in the MENA region.[37]

Street demonstrations began on a regional level and quickly gained trans-regional momentum, gaining international attention in the process. All attempts to violently suppress the uprising, including shutting down Internet access, proved fruitless. “Still the uprising continued, and the army made the decision ultimately not to act against the protesters. Mubarak’s weak concessions … failed to appease the Egyptian people’s demands. On 11 February, a day of massive ‘Friday of Departure’ demonstrations, Mubarak was finally forced to resign.” [38]

Figure 3: Egyptian Internet Traffic between 28 January and 2 February 2011.

Source: Arab Social Media Report, “Civil Movements: The Impact of Facebook and Twitter,” 3; available at www.dsg.ae/portals/0/ASMR2.pdf.

In the beginning of the unrest, the Facebook page named “Kulluna Khalid Said” (“We are all Khalid Said”), named after a blogger who the police had caned to death, rapidly acquired more than one million followers.[39] It aimed at organizing protests against the regime, and quickly became one of the most crucial websites for the anti-regime movement. Although there had already been protests in Egypt following the rigged 2010 elections, there is little doubt that the events in Tunisia triggered the uprising in Egypt.[40]

The actual revolution barely lasted eighteen days, with the government reacting in ways that had become traditional for authoritarian regimes, using disproportionate force against protesters. Initially surprised by events in Tunisia, but convinced that those concerns did not apply to Egypt, the mood quickly changed. Tahrir Square in Cairo, which was occupied by protesters and rapidly came to be focal point of the revolution, was surrounded by the Egyptian Army and gangs of thugs loyal to the Mubarak regime. Internet and mobile communications were temporarily shut down (see Figure 3 above), and anti-activist measures were undertaken on the Web – all to no avail.

The revolution had already acquired critical mass and momentum, and the protesters had broadened their base beyond those who read Facebook and Twitter messages or were physically present in Tahrir Square. Communication shutdowns by the regime proved fruitless, as the public could witness regime brutality live on Al-Jazeera, further strengthening the protesters’ resolve.[41] Social media made the public feel that they were part of the movement. Consequently, the fear of regime suppression was greatly reduced, and the protests continued. An additional crucial factor was the support of the Muslim Brotherhood. Their level of organization and countrywide deployment aided anti-government action and ultimately served as a guarantor for initial success. Social media helped the movement gain international support, making governments around the world shy away from the “doomed” Mubarak regime. The conflict became more violent, causing many casualties and leading to an increasingly chaotic situation. The traditionally strong and respected Egyptian military stepped in, and for a week provided protection for the protesters in Tahrir Square.[42] The protest movement was well coordinated and had strong public support; from this position of strength it was able to refuse all proposals from the Mubarak government.

In the end, the Egyptians toppled the Mubarak regime by their own efforts and with the help of the military, who did not leave a power vacuum but helped to maintain order.[43] However, two serious consequences emerged. First, the main goal of the protest movement—to replace the government with a new, more participatory and open one—was not achieved (as subsequent events in Egypt have shown all too clearly). Second, with far higher stakes at play regionally and globally, it demonstrated that if the unsatisfied population could overthrow the Egyptian government, any government in the MENA region, which all face similar problems, were potentially in trouble. Not completely unexpected, Libya was the next country to encounter the people’s newly discovered power.

Libya and Beyond

Although the actual situation in Libya was slightly different from that in neighboring states, the underlying problems were essentially identical to those described above. The big difference in the anti-government protest was the almost immediate turn to violence and the subsequent shift to outright civil war. This is the reason why this article will not look at Libya in detail, but will utilize it as transition to the other revolutions in the region.

Following the fall of the Mubarak regime in Egypt, young Internet activists in Libya called for demonstrations for Friday 17 February 2012, declaring it “the day of anger.” However, another event became the igniting factor: the arrest of an attorney from Benghazi who was representing relatives of political prisoners who were massacred in a revolt a few years earlier. This immediately led to demonstrations, which spread rapidly throughout the country. Those security forces that did not change sides countered the uprising with the utmost brutality. The military was quickly deployed to fight its own population with every weapon in its considerable arsenal.[44] Social media not only provided the public with video footage of the regime’s atrocities, it did also created a pan-Arab mood for change. Following the toppling of the regimes in Tunisia and Egypt, social media quickly made the outbreak of civil war in Libya not only a regional problem, but a broader international one as well. The Arab League suspended Libya’s membership and asked the United Nations for the establishment of a no-fly zone. Considering the regime’s military strength, a war ensued that could not be won as quickly as the public expected.[45]

Social media did not play a direct role in coordinating the war effort, as international forces provided the opposition with communications equipment, mainly satellite telephones. However, as is the case of any war in the Information Age, it was also a war about public opinion in the neighboring states, which largely played out on Al-Jazeera. With hindsight, the quick veer towards civil war followed by direct international intervention made the Libyan case more unique in the context of the Arab Spring. Social media had little time to assert their potential, but rather acted as a tool on the tactical level to gain support and to denounce atrocities of the other side. This in the end brought about the international intervention that helped bring the war to a swifter end.

At the same time, anti-regime protests spread into Yemen, Bahrain, and Syria. In Yemen the ruling president managed to gather enough support to drag out the process and (following political intervention from the Gulf Cooperation Council, or GCC) deliver a compromise that in the end brought about a regime change. During the protests, social media were used to gather support and to direct strike actions across the country, thereby making it clear to the regime that continuing as before was not an option.

In Bahrain, the protest movement was initially more moderate, calling for demonstrations via Facebook, demanding political and social change. After a flaring of violence the conflict quieted down, following an intervention by the GCC (mainly Saudi Arabia) and a proposal from the government to enter into a “dialogue of national consensus.” In a way, the protest movement was suppressed successfully also by the use, or rather the absence of the media. Qatar-based Al-Jazeera showed a remarkable lack of interest in the conflict, thus taking away the movement’s main source of regional and global media coverage. The public stage was thereby reduced considerably, and the impact of the protests narrowed.[46]

Due to its limited scope, this essay will not look at the other countries affected by the Arab Spring. Suffice it to say that the conduct and outcomes of the uprisings vary from country to country, and have so far brought about elections in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya (and, at the other end of the spectrum, a bloody and protracted civil war in Syria). However, so far results show that free elections alone do not solve problems. As the underlying reasons for the revolts have not been conclusively addressed, much remains yet to be done in order to achieve a peaceful transition on the road to prosperity. For many of the other countries in the MENA region, the protest movements and the demand for socio-political change are still ongoing, and it is too early to evaluate the complete consequences for the MENA region as well as its potential global geopolitical impact.

Assessment: Past and Future Impact

Media Revolutions?

As was shown above, “the situations in Tunisia and Egypt have both seen an increased use of social networking media such as Facebook and Twitter to help organize, communicate, and ultimately initiate civil-disobedience campaigns and street actions.” [47] It has also been demonstrated that social media alone would not be able to carry through a revolution from start to finish:

Calling the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt Twitter or Facebook revolutions overlooks social media access in these countries. In 2009 in Tunisia and Egypt there were only 34.1 and 24.3 Internet users per 100 inhabitants respectively. Furthermore, in Egypt only 7 % of inhabitants are Facebook users, while 16 % use the platform in Tunisia. Facebook use is highest in the United Arab Emirates (36 %), Bahrain (29 %), Qatar (24 %) and Lebanon (23 %). Of these countries, only one (Bahrain) experienced significant protests. From the social media access and usage it is clear that there is no necessary correlation between social media access and unrest.[48]

It can be argued that, although social media can act as a catalyst for change, the will to revolt needs underlying reasons. And this is more likely to occur within authoritarian regimes than in democracies.

The Arab Spring has been dubbed “Revolution 2.0,” implying that without social media the uprisings would not have taken place.[49] On the other hand “the significance of social media was definitely there but should neither be under- or overstated.” [50] It seems more convincing, rather, that the uneven demographic distribution within these societies and the perceived unfairness of the ruling regimes were the actual factors for change. It has been shown that the impact and

the mobilizing effect of new information and social media networks as catalysts of broad socio-political protest will vary significantly from region to region and from one political context to another. The presence of multiple underlying causes for socio-political protest will not suffice for new information and communication networks to become a major catalyst. For one, Internet access must be available to significant segments of the population. In the foreseeable future, this condition will exclude a number of underdeveloped countries with minimal Internet penetration.[51] Therefore traditional media such as satellite TV and radio will continue to play a major role in informing and mobilizing the masses such as Al-Jazeera during the Arab Spring. While it was reluctant in broadcasting events from Bahrain it practically took the side of the protest movement in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya.[52]

Country | Est. # of active twitter users (Avg. b/n 1 Jan and 30 Mar 2011) | Twitter penetration* (%) | Number of Facebook users (4/5/2011) | Facebook penetration* (%) | Internet users per | Mobile Subscriptions per 100 ** |

Algeria | 13,235 | 0.04 | 1,947,900 | 5.42 | 13.47 | 93.79 |

Bahrain | 61,896 | 7.53 | 302,940 | 36.83 | 53.00 | 177.13 |

Comoros | 834 | 0.12 | 9,080 | 1.28 | 3.59 | 18.49 |

Djibouti | 4,046 | 0.45 | 52,660 | 5.89 | 3.00 | 14.90 |

Egypt | 131,204 | 0.15 | 6,586,260 | 7.66 | 24.26 | 66.69 |

Iraq | 21,625 | 0.07 | 723,740 | 2.24 | 1.06 | 64.14 |

Jordan | 55,859 | 0.85 | 1,402,440 | 21.25 | 26.00 | 95.22 |

Kuwait | 113,428 | 3.63 | 795,100 | 25.51 | 36.85 | 129.85 |

Lebanon | 79,163 | 1.85 | 1,093,420 | 25.50 | 23.68 | 56.59 |

Libya | 63,919 | 0.96 | 71,840 | 1.08 | 5.51 | 77.94 |

Mauritania | 1,407 | 0.04 | 61,140 | 1.78 | 2.28 | 66.32 |

Morocco | 17,384 | 0.05 | 3,203,440 | 9.78 | 41.30 | 79.11 |

Oman | 6,679 | 0.23 | 277,840 | 9.37 | 51.50 | 139.54 |

Palestine | 11,369 | 0.25 | 595,120 | 13.10 | 32.23 | 28.62 |

Qatar | 133,209 | 8.46 | 481,280 | 30.63 | 40.00 | 175.40 |

SaudiArabia | 115,084 | 0.43 | 4,092,600 | 15.28 | 38.00 | 174.43 |

Somalia | 4,244 | 0.04 | 21,580 | 0.22 | 1.16 | 7.02 |

Sudan | 9,459 | 0.02 | 443,623 | 1.01 | 9.19 | 36.29 |

Syria | 40,020 | 0.17 | 356,247 | 1.55 | 20.40 | 45.57 |

Tunisia | 35,746 | 0.34 | 2,356,520 | 22.49 | 34.07 | 95.38 |

UAE | 201,060 | 4.18 | 2,406,120 | 50.01 | 75.00 | 232.07 |

Yemen | 29,422 | 0.12 | 340,800 | 1.37 | 9.96 | 35.25 |

Figure 4: Facebook, Twitter, Internet and Mobile Subscription Rates in the Arab Region.

Source: Arab Social Media Report, “Civil Movements: The Impact of Facebook and Twitter,” 29; available at www.dsg.ae/portals/0/ASMR2.pdf.

However, “social media are tools that allow revolutionary groups to lower the costs of participation, organization, recruitment and training. But like any tool, social media have inherent weaknesses and strengths … and no doubt offer advantages in disseminating messages quickly and broadly, but they also are vulnerable to government counter-protest tactics.” [53] In the coming years their influence is likely to grow, with the younger generation using these technologies as integral parts of their everyday life. Additionally, social media penetration across all sectors of society will likely increase as well. The governments in the MENA region overall reacted poorly to the new media technologies. Many mistakes were made, as the ruling elite had neither an understanding of social media or its impact on their actions. Drawing on the experiences during the Arab Spring, the next section will extract some patterns and try to apply them to the democratic context, assess the potential impact on future security policy, and attempt to formulate certain policy recommendations that would generally enable governments to adapt to this new dimension.

Blessing or Curse?

This article has shown so far that the use of social media has undeniable implications for governments, especially (but not exclusively) in internal conflict situations. As Ivan Sigal writes, “It is now clear that increased access to information and to the means to produce media has both positive and negative consequences in conflict situations. The question of whether the presence of digital media networks will encourage violence or lead to peaceful solutions may be viewed as a contest between the two possible outcomes. … However, it is equally possible for digital media to increase polarization, strengthen biases, and foment violence.” [54] But it has also been shown that social media can act more like a tool, and can serve as a catalyst to more widespread popular action, rather than causing revolutions or anti-government action on their own. Underlying reasons are required to actually instigate mass protest movements on a revolutionary scale.

Social media create an alternative communication infrastructure that is difficult to control, theoretically allowing nationwide and even region-wide concerted action, which could seriously threaten a regime’s stability. As Papic and Noonan observe, “Current conventional wisdom has it that social networks have made regime change easier to organize and execute. An underlying assumption is that social media [are] making it more difficult to sustain an authoritarian regime—even for hardened autocracies like Iran and Myanmar—which could usher in a new wave of democratization around the globe.” [55]

The flow of information on social media suggests an alleged objectivity. This is a crucial aspect in the quest for internal and external support. Papic and Noonan state: “Foreign observers—and particularly the media—are mesmerized by the ability to track events and cover diverse locations, perspectives and demographics in real time. … Social media no doubt offer advantages in disseminating messages quickly and broadly, but they also are vulnerable to government counter-protest tactics.” [56]

As with any other instruments, there are two sides to the use of social media. There is not only inherent strength in their use, but also an accompanying weakness, as social media platforms eliminate operational security to a minimum. Social media, “as well as being possible instruments of protest, can also render users vulnerable to state surveillance. These platforms have been used by security and intelligence agencies to identify and locate activists and protesters.” [57] Thereby these instruments can “quickly turn into a valuable intelligence-collection tool. A reliance on social media can also be exploited by a regime willing to cut the country off from Internet or domestic text messaging networks altogether, as has been the case in Egypt.” [58] It can also be used to track down and locate leaders of anti-government movements. As Wikileaks’ Julian Assange recently noted, the Internet is not only a force for openness and transparency, “it is also the greatest spying machine the world has ever seen. The capabilities of such a surveillance machine can be amplified by social networking platforms like Facebook that link an online identity to (most often) a user’s real name, place of residence and work, interests, pictures, and network of friends.” [59]

Due to the fact that most mobile phones have built-in GPS receivers and use many applications with geo-location functionality in the background (i.e., without the user’s knowledge), intelligence agencies are not only able to connect virtual identities with real persons but are equally able to track them in real-time (online) via their mobile phones. This dramatically increases the surveillance capabilities of governments. Papic and Noonan note that “Facebook profiles, for example, can be a boon for government intelligence collectors, who can use updates and photos to pinpoint movement locations and activities and identify connections among various individuals, some of whom may be suspect for various activities.” [60] In this respect social media and their use in anti-government movements are more of a blessing than a nuisance for the respective government. Additionally, social media offer another bonus for governments, as they are not only useful to cover protests but also to help steer protests in certain directions through the use of misinformation, fake identities, and cleverly placed counter-propaganda. As Alex Comninos observes, “Social networks can very quickly become mechanisms for spreading rumor and falsehood and, as there is usually no moderation of this content, it becomes the responsibility of the user to critically examine the veracity of claims made on these platforms.” [61]

Intelligence agencies have learned to use social media to their advantage. By using fake identities, they are able to create an illusion of support for ideas. They are also able to challenge ideas on social media platforms by inserting counter-arguments that appear to come from the “grass-roots” level of the movement, by disseminating “views over social media that appear to be the legitimate and spontaneous voices of a grass-roots movement, but are actually campaigns by individuals, corporations, or governments. The goal of such campaigns is to disguise the efforts of a political and/or commercial entity as an independent public reaction to some political entity—a politician, political group, product, service or event” [e.g., the practice known as “astroturfing”].[62]

Another commonly used counter-protest tactic

is to spread disinformation, whether it is to scare away protesters or lure them all to one location where anti-riot police lie in wait. We have not yet witnessed such a government ‘ambush’ tactic, but its use is inevitable in the age of Internet anonymity. Government agents in many countries have become quite proficient at trolling the Internet in search of pedophiles and wannabe terrorists. (Of course, such tactics can be used by both sides. During the Iranian protests in 2009, many foreign-based Green Movement supporters spread disinformation over Twitter to mislead foreign observers).[63]

In summary, it can be stated that social media could benefit both sides as much as they can hinder the achievement of each side’s respective goals. Comninos states: “User content created on mobile phones and instantly disseminated on the Internet was a powerful tool in the hands of the regime security and intelligence forces, as well as protesters, and social media could also be used to spread fear or disinformation. Social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter could be used to spy on protesters, find out their real-life identities and make arrests and detentions.” [64] As already stated, the exploitation of social media is truly a double-edged sword. However, one factor stands out as most important: social media as a tool are too powerful to ignore, which is true for both sides of a conflict. Their potential is far from being fully explored, made more difficult by their constantly changing nature. They will have consequences for future security policies, both for authoritarian regimes as well as for democratic countries.

Policy Implications

To this point this essay has illustrated that social media “can transform information sharing into knowledge production. But they can also be used for control and manipulation of citizens.” [65] It has shown that sharing information via social media is likely to increase globally, and that it exhibits especially high growth rates in present conflict-prone areas. Therefore, one could argue that the information space will be a contested area, one that cannot be ignored by governments. As Drapeau and Wells note, “The proliferation of social software has ramifications for (U.S.) national security, spanning future operating challenges of a traditional, irregular, catastrophic, or disruptive nature. Failure to adopt these tools may reduce an organization’s relative capabilities over time. Globally, … [g]overnments that harness its potential power can interact better with citizens and anticipate emerging issues.” [66] This means that social media cannot be ignored, and governments are required to act in the contested information space. This demands a comprehensive cyber-strategy considering both the dangers and possibilities of the new technology, in the sense that “social media can also be employed at the same time both for defense activities (prevention, warning, institutional communication, crisis management, counter-propaganda) and for offensive actions (influence, propaganda, deception).” [67] Events during the Arab Spring demonstrated that ignoring social media is no longer an option. At the same time, a brute force approach that moves by completely shutting down Internet access, as was attempted during the Egyptian revolution, has not proven successful either. On the contrary, it even had negative consequences for business and administration, which are both increasingly dependent on Internet access. Hence, it can be argued that “command-and-control approaches to media are likely to fail in a networked, participatory media environment. Attempts to either restrict or dominate media flows are counterproductive in many cases, as people everywhere increasingly have diverse options for creating, receiving, and sharing information.” [68]

So how can governments use social media advantageously? In short, it requires a strategic and holistic understanding of the topic in order to develop a workable comprehensive strategy. On a national level, all aspects have to be studied to be able to successfully deal with the existence of social media. Apart from data mining, the most obvious direct opportunities for the use of social media arise in:

Warning, surveillance, and trend analysis

Deception and influence

Institutional information sharing.

The early warning and surveillance aspect is of major importance to all governments, as it is crucial in order to avoid strategic surprise, prolong warning times ahead of events, and decrease vulnerability to unexpected developments. In this context, social media cannot only act as intelligence collection tools, as described earlier, but also as an early warning system against future security threats and malicious activities. As the utilization of social media—not only by anti-government movements, but also by opposing states as well as criminal organizations and terrorist groups—is increasing steadily, the potential for intelligence collection is enormous, especially since the nexus between terrorists and organized crime is becoming dramatically more interdependent.[69] The potential for early warning against the highest priority security threat in the world today—terrorism—is growing. In this connection, social media can be employed to obtain “the first signs of a hostile or potentially dangerous activity for a state’s security.” [70] Respective measures could encompass the analysis of messages shared online, the scan of threads and blogs dealing with hacker activity, and the examination of guerrilla recruitment and instruction videos disseminated via virtual platforms in order to “understand the attack methods and techniques and devise effective methods to react and to counter the terrorist threat; the continuous control of a Facebook profile updates and a careful exam of the photos published on that very profile can allow [a government] to trace the movements and the activities of the members of a criminal group and [map] their connections, etc.” [71]

Trend analysis is aimed at analyzing and forecasting the actions of possible opposing groups through the observation of social media networks in order to extract possible long-term tendencies. Advanced content analysis would enable security services to predict evolutions in cyberspace before they actually happen in the real world.[72] An example of such a project is one initiative launched by the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI),

called Open Source Indicators (OSI), [which] means to actively … [develop] automatic systems for provisional analysis applied to forestalling national security related events: political crises, migrations, epidemics, humanitarian emergencies, protests, periods of economic instability, etc. In particular, OSI is based on the principle that relevant social events are always anticipated by changes of behavior through the population (increase/reduction of communication, consumes, movements, etc.). Plotting and studying such behaviors can, in fact, be useful to anticipate the events themselves.[73]

This would not only indicate future trends, but also would point out suitable points of connection or other key nodes where a deception or influence campaign might be inserted in order to counter possible future threats before they develop further. Here

the use of social media allow … [observers to describe] events, model reality, influence the perception of a certain situation, a specific issue or a person, and influence choices and behaviors. Therefore, social media can strongly affect institutional, business or team strategic decision-making, as well as formation and development of the public opinion’s collective awareness. These tools can be employed to interfere with the adversaries’ decision-making process, both directly, that is by manipulating their information and analysis framework or by influencing their close collaborators, and indirectly: by influencing groups of people (i.e., political parties, trade unions, public opinion, etc.) whose reactions affect the very choices of a country’s leadership.[74]

Several programs that aim at exactly those purposes—data mining, early warning, and influence campaigns—have already been installed to that effect in numerous countries. These programs are most prominently operated by the United States, but other countries are catching up quickly.[75]

However, acquiring indispensable intelligence is just one part of a comprehensive strategy. As many historic examples have shown, it is one thing for a government to acquire information, but quite another to share it with the necessary agencies in order to develop an appropriate response.[76] An overall institutional information sharing strategy is another part of the required policy package in order to act successfully. To this end, there are two main aspects: an internal element, connecting relevant government agencies in an intra-institutional network, and an external element connecting the government with its people. Both have different obstacles to overcome in order to be applied.

Internally, a common dilemma—especially within intelligence circles—is the balance between the need for security and the necessity to share information. This is actually one of the main reasons information mishaps occurred in the past. However, one cannot ignore the need for security. As Drapeau and Wells note, “security, accountability, privacy, and other concerns often drive national security institutions to limit the use of open tools such as social software, whether on the open web or behind government information system firewalls. Information security concerns are very serious and must be addressed, but to the extent that our adversaries make effective use of such innovations, our restrictions may diminish our national security.” [77] In other words, adapting to the new technology is of the utmost importance, as possible adversaries already take advantage of those potentials. The effective utilization of social media adds significantly to the ability to quickly disseminate information among government agencies and to build up a common operational intelligence picture where every civil servant can contribute and make use of the information available and create “living intelligence.” [78] A good example of such a policy initiative is the A-Space initiative, a collaborative platform aimed at improving intelligence sharing inside the U.S. intelligence community. So it can be argued that overall the government side has overtaken its opponents in reaping the benefits of social media in the conflict sphere.

The external dimension also adds an international element to the equation, as “networked media require different policy approaches with regard to state boundaries. Information and communications development policies that focus exclusively on nation-states neglect the regional and global nature of networked media, and of the impact of international satellite television.” [79] That means a decision of a local character can, via social media, quickly get regional or even global attention. This would then increase the requirement for international cooperation far beyond the present level, again relying more heavily on authoritarian regimes where openness is not part of the present policy spectrum.

Conclusion

So what conclusions can be derived from the material and considerations presented so far? And what is the potential impact of social media, particularly on authoritarian regimes? Social media have a profoundly higher impact on everyday life than was likely originally planned or anticipated. They have changed the way people interact with each other; how they view, share, and influence information; and they have also generated completely new relationships. The shift from one-to-many towards many-to-many communications, with the possibility of personal interaction and participation, has brought about many dramatic changes in modern society, including in the context of conflict.

The combined power of the various social media applications has enormous potential to shape events. Due to two main features, this extends social media’s impact beyond merely affecting its users. First, secrets are (almost) impossible to keep. Second, social media provide an additional platform for civil society to influence the public sphere, increasing the need for transparency and participation accordingly.

This article revealed how state and non-state actors experiencing intra-state conflict, such as the Arab revolutions, have used social media and what impact social media had on these events. It established how social media can both be a curse and a blessing. Furthermore, the paper extracted patterns and applied them to the democratic context, and assessed the potential impact on future security policies. It formulated certain policy recommendations that would enable governments to adapt to this new dimension in the conflict spectrum.

Governments’ previous monopoly on information has been massively reduced, especially in the case of authoritarian regimes, which have traditionally relied upon control over the distribution and availability of information via dominance of the media as one pillar of their power. The borderless nature of social media has the capability to rapidly expand a local issue to a regional or trans-regional one, reducing the possibilities for control at the same time. Social media have already had an impact on information distribution in the framework of conflict, making it a valuable tool in the increasingly important struggle for national and international public opinion in conflict situations.

As the case studies from the Arab Spring have demonstrated, those elements actually increase the political cost of using violence against protesters, and can have a negative impact on public opinion. Likewise, it reduces the costs faced by protest movements, which can use social media as tools for recruitment, coordination, and mobilization, making broad participation easier and global support more likely to occur. However, although social media can act as catalysts for change, the will to actually revolt needs underlying causes.

This essay has shown that social media have inherent strengths and weaknesses. They offer quick information distribution possibilities, but also reduce operational security to a minimum and create vulnerabilities to surveillance, control, and manipulation by adversaries, making their use a two-edged sword.

The Internet and social media have implemented new realities in regard to communications. Metaphorically speaking, people have moved closer together information-wise, creating a kind of “global village” with the possibility of instantaneous and exhaustive information sharing. This intensified networking has created a kind of swarm behavior of the masses, who may lack leadership but are nevertheless difficult to steer against their inherent wishes and are practically impossible to stop once a movement is set in motion, especially a political transformation. Counting on the masses’ inertia is no longer an option for governments, because public opinion can shift quickly under the influence of social media.

This paper has illustrated that social media and their impacts cannot be ignored without consequences, and that they demand a comprehensive, flexible, properly implemented and resourced public campaign and cyber-strategy to cope with social media’s constantly changing nature and impact. Furthermore, future governance needs to adapt to the new realities of the Internet age and the increased need for transparency and participation.

Therefore, social media are a tool that is too powerful to ignore, and if “utilized properly, [are] expected to yield numerous advantages: improve understanding of how others use the software, unlock self-organizing capabilities within the government, promote networking and collaboration with groups outside the government, speed decision-making, and increase agility and adaptability.” [80] This article has shown that even though the majority of the current literature on social media argues that it enhances the political power of the people, there is a shift in the balance under way. Governments have demonstrated great adaptability and are beginning to use social media to their advantage. However, in order to employ social media to its full potential, governments must become more transparent while maintaining an outward-looking approach to their people. Transparency will necessarily need to be accompanied by more truthfulness in governments’ decision-making processes and actions, as social media increase the cost of dishonesty. Especially for autocratic governments, this generates problems by itself, as making their present methods transparent would create immediate outcry from the population. A stronger participatory and transparent approach seems necessary in order to cope with the new realities.

For countries with a high degree of public participation inherent in the system, like Switzerland, adaptation would primarily be a technical issue. More closed and autocratically ruled countries, though, would have to change the way they govern their citizens before being able to implement these policies and to eliminate the potential dangers of the new technology to their status quo. This would encompass quite radical systemic changes that could deprive the authorities of their former power basis. It is, of course, highly doubtful that an authoritarian government that presently maintains its hold on power via careful information control and oppressive use of their security apparatus would risk such a step, rather than trying to control the use of the Internet by its citizens. Without a doubt “the expansion of Internet connectivity does create new challenges for domestic leaders who have proved more than capable of controlling older forms of communication. This is not an insurmountable challenge, as China has shown, but even in China’s case there is growing anxiety about the ability of Internet users to evade controls and spread forbidden information.” [81]

Whether the increasing penetration of social media across global society will ultimately lead to an upsurge in the democratization process in countries hitherto less inclined to follow that path is difficult to answer. And whether such a process would create a better world is also a question that would need to be explored, as the upheavals in the Middle East and North Africa have shown. It is far easier to revolt than to make things better. Neither social media nor revolutions alone can eradicate the underlying societal and economic problems that create the conditions for an uprising in the first place.

* The author has worked in the field of security for more than 25 years. This article was originally written as a research paper completed toward a Master of Advanced Studies in International and European Security at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy.

[1] Wael Ghonim, Revolution 2.0 (London: Fourth Estate, 2012).

[2] See Marko Papic and Sean Noonan, “Social Media as a Tool for Protest,” Security Weekly (3 February 2011); available at http://www.stratfor.com/weekly/20110202-social-media-tool-protest.

[3] International Telecommunication Union, “Trends in Telecommunication Reform 2012: Smart Regulation for a Broadband World” (Geneva, 2012); available at www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/reg/D-REG-TTR.13-2012-SUM-PDF-E.pdf.

[4] The Radicati Group, Inc., “Social Networking Market 2011-2015” (March 2011); available at www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Social-Networking-Market-2011-2015-Executive-Summary.pdf.