Foreign Terrorist Organization Designation Process and U.S. Agency Enforcement Actions *

Highlights

Main Findings

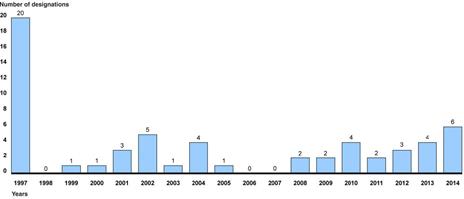

The Department of State (State) has developed a six-step process for designating foreign terrorist organizations (FTO) that involves other State bureaus and agency partners in the various steps. State’s Bureau of Counterterrorism (CT) leads the designation process for State. CT monitors terrorist activity to identify potential targets for designation and also considers recommendations for potential targets from other State bureaus, federal agencies, and foreign partners. After selecting a target, State follows a six-step process to designate a group as an FTO, including steps to consult with partners and draft supporting documents. During this process, federal agencies and State bureaus, citing law enforcement, diplomatic, or intelligence concerns, can place a “hold” on a potential designation, which, until resolved, prevents the designation of the organization. The number of FTO designations has varied annually since 1997, when 20 FTOs were designated. As of December 31, 2014, 59 organizations were designated as FTOs, with 13 FTO designations occurring between 2012 and 2014.

Source: GAO analysis of State documents. | GAO-15-629

Figure 1: Number of Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, 1997 through

2014, by Year of Designation.

State considered input provided by other State bureaus and federal agencies for all 13 of the FTO designations made between 2012 and 2014, according to officials from the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, State, and the Treasury, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and GAO review of agency documents. For example, State used intelligence agencies’ information on terrorist organizations and activities to support the designations.

U.S. agencies reported enforcing FTO designations through three key legal consequences—blocking assets, prosecuting individuals, and imposing immigration restrictions—that target FTOs, their members, and individuals that provide support to those organizations. The restrictions and penalties that agencies reported imposing vary widely. For example, as of 2013, Treasury has blocked about $ 22 million in assets relating to 7 of 59 designated FTOs.

Abbreviations

| CT | Bureau of Counterterrorism |

| Defense | Department of Defense |

| DHS | Department of Homeland Security |

| E.O. 13,224 | Executive Order 13,224 |

| FTO | Foreign Terrorist Organization |

| ISIL | Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant |

| ISIS | Islamic State of Iraq and Syria |

| Justice | Department of Justice |

| ODNI | Office of the Director of National Intelligence |

| OFAC | Office of Foreign Assets Control |

| SBU | Sensitive But Unclassified |

| State | Department of State |

| Treasury | Department of Treasury |

Introduction

U.S. agencies, including components of the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, State, and the Treasury, and the intelligence community, have implemented procedures to collect and share information about and take action on terrorists posing a threat to the national security of the United States. The Secretary of State, in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Attorney General, may identify and designate certain groups as foreign terrorist organizations (FTO), a designation that can result in criminal and civil penalties, as well as other financial and immigration consequences for designated FTOs or those who provide support to FTOs. Congress has recently expressed concerns about the designation process.

You asked us to provide information on the designation of FTOs. In this report, we provide information on (1) the process for designating FTOs, (2) the extent to which the Department of State (State) considers input from other agencies during the FTO designation process, and (3) the consequences that U.S. agencies impose as a result of an FTO designation.

To identify the FTO designation process, we identified the steps in the FTO designation process by reviewing the legal requirements for designation and the legal authorities granted to State and other U.S. agencies to designate FTOs. In addition, we reviewed State documents that identified and outlined State’s process to designate an FTO. To assess the extent to which State considered input from other agencies during the FTO designation process, we interviewed officials from the Departments of Defense (Defense), Homeland Security (DHS), Justice (Justice), State, and the Treasury (Treasury), as well as officials from the intelligence community, to determine for the 13 FTOs designated between 2012 and 2014 when information on organizations considered for FTO designation is provided to State by its consulting partners, as well as the nature of that information. We defined consideration as any action of State to request, obtain, and use information from other federal agencies, as well as letters of concurrence from those agencies. To identify the consequences U.S. agencies impose as a result of FTO designation, we (1) reviewed Treasury reports on blocked funds for FTOs from 2008 through 2013, (2) reviewed data on the public/unsealed terrorism and terrorism-related convictions to identify individuals who provided material support or resources to an FTO or received military-type training from an FTO between 2009 and 2013, and (3) analyzed data from State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs reports on visa denials between fiscal years 2009 and 2013. We also reviewed the U.S. Customs and Border Protection enforcement system database on arrival inadmissibility determinations between fiscal years 2009 and 2014, and information from DHS’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement on deportations between fiscal years 2013 and 2014. In each instance, we analyzed the data provided by the agencies, performed basic checks to determine the reasonableness of the data, and discussed the data with relevant agency officials to confirm the totals presented. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report. See appendix I for more details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2015 to June 2015 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

This report is a public version of a sensitive but unclassified (SBU) report that was issued on April 21, 2015. State regarded some of the material in that report as SBU information, which must be protected from public disclosure and is available for official use only. This public version of the original report does not contain certain information regarding the duration of FTO designations between 2012 and 2014 that State deemed to be SBU.

Background

FTO Designation Authority

Under section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended, the Secretary of State, in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Attorney General, is authorized to designate an organization as an FTO.[1] For State to designate an organization as an FTO, the Secretary of State must find that the organization meets three criteria:

It is a foreign organization.

The organization engages in terrorist activity or terrorism, or retains the capability and intent to engage in terrorist activity or terrorism.[2]

The organization’s terrorist activity or terrorism threatens the security of U.S. nationals or the national security of the United States.

Designation of a terrorist group as an FTO allows the United States to impose certain legal consequences on the FTO, as well as on individuals that associate with or knowingly provide support to the designated organization. It is unlawful for a person in the United States or subject to the jurisdiction of the United States to knowingly provide “material support or resources” to a designated FTO, and offenders can be fined or imprisoned for violating this law.[3] In addition, representatives and members of a designated FTO, if they are not U.S. citizens, are inadmissible to and, in certain circumstances, removable from the United States.[4] Additionally, any U.S. financial institution that becomes aware that it has possession of or control over funds in which a designated FTO or its agent has an interest must retain possession of or control over the funds and report the funds to Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.[5]

Other Terrorist Designation Authorities

In addition to making FTO designations, the Secretary of State can address terrorist organizations and terrorists through other authorities, including listing an individual or entity that engages in terrorist activity under Executive Order 13,224 (E.O. 13,224).[6] E.O. 13,224 requires the blocking of property and interests in property of foreign persons the Secretary of State has determined, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Secretaries of the Departments of Homeland Security and the Treasury, to have committed or to pose a significant risk of committing acts of terrorism that threaten the security of U.S. nationals or the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.[7] E.O. 13,224 blocks the assets of organizations and individuals designated under the executive order. It also authorizes the blocking of assets of persons determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Secretaries of State and Homeland Security, to assist in; sponsor; or provide financial, material, or technological support for, or financial or other services to or in support of, designated persons, or to be otherwise associated with those persons. In practice, when State designates an organization as an FTO, it also concurrently designates the organization under E.O. 13,224.[8] Once State designates an organization under E.O. 13,224, Treasury is able to make its own designations under E.O. 13,224 of other organizations and individuals associated with or providing support to the organization designated by State under E.O. 13,224. These designations allow the U.S. government to target organizations and individuals that provide material support and assistance to FTOs.[9]

State Uses a Six-Step Process for Designating Foreign Terrorist Organizations

State has developed a six-step process for designating foreign terrorist organizations. State’s Bureau of Counterterrorism (CT) leads the designation process for State, and other State bureaus and agency partners are involved in the various steps. While the number of FTO designations has varied annually since the first 20 FTOs were designated in 1997, as of December 31, 2014, 59 organizations were designated as FTOs.

FTO designation activities are led by CT, which monitors the activities of terrorist groups around the world to identify potential targets for designation.[10] When reviewing potential targets, CT considers not only terrorist attacks that a group has carried out but also whether the group has engaged in planning and preparations for possible future acts of terrorism or retains the capability and intent to carry out such acts. CT also considers recommendations from other State bureaus, federal agencies, and foreign partners, among others, and selects potential target organizations for designation. For an overview of agencies and their roles in the designation process, see appendix II. After selecting a target organization for possible designation, State uses a six-step process it has developed to designate a group as an FTO (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: State’s Six-Step Process for Designating Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO).

- Step 1: Equity check – The first step in CT’s process is to consult with other State bureaus, federal agencies, and the intelligence community, among others, to determine whether any law enforcement, diplomatic, or intelligence concerns should prevent the designation of the target organization. If any of these agencies or other bureaus has a concern regarding the designation of the target organization, it can elect to place a “hold” on the proposed designation, which prevents the designation from being made until the hold is lifted by the entity that requested it. The equity check is the first step where an objection to a designation can be raised; however, in practice, a hold can be placed at any step in the FTO designation process prior to the Secretary’s decision to designate.

- Step 2: Administrative record – As required by law, in support of the proposed designation, CT is to prepare an administrative record, which is a compilation of information, typically including both classified and open source information, demonstrating that the target organization identified meets the statutory criteria for FTO designation.[11]

- Step 3: Clearance process – The third step in CT’s process is to send the draft administrative record and associated documents to State’s Office of the Legal Adviser and then to Justice and Treasury for review and approval of a final version to submit to the Secretary of State. For clearance, Justice and Treasury are to review the draft administrative record prepared by State and may suggest that State make changes to the document. The interagency clearance process is complete once Justice and Treasury provide State with signed letters of concurrence indicating that the administrative record is legally sufficient. CT is then to send the administrative record to other bureaus in the State Department for final clearance.

- Step 4: Secretary of State’s decision – Materials supporting the proposed FTO designation are to be sent to the Secretary of State for review and decision on whether or not to designate. The Secretary of State is authorized, but not required, to designate an organization as an FTO if he or she finds that the legal elements for designation are met.

- Step 5: Congressional notification – In accordance with the law, State is required to notify Congress 7 days before an organization is formally designated.[12]

- Step 6: Federal Register notice – State is required to publish the designation announcement in the Federal Register and, upon publication, the designation is effective for purposes of penalties that would apply to persons who provide material support or resources to designated FTOs.[13]

Fifty-nine Organizations Are Currently Designated as FTOs

As of December 31, 2014, there were 59 organizations designated as FTOs, including al Qaeda and its affiliates, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL),[14] and Boko Haram. See appendix III for the complete list of FTOs designated, as of December 31, 2014. The number of FTO designations has varied annually since the first FTOs were designated, in 1997.[15]State designated 13 groups between 2012 and 2014. Figure 2 shows the number of organizations designated by year of designation, as of December 31, 2014.

Source: GAO analysis of State documents. | GAO-15-629

Note: This figure includes the 59 FTOs designated as of December 31, 2014. It does not include 10 organizations that were previously designated and whose designations were subsequently revoked by the Secretary of State. The Secretary of State, in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Attorney General, may revoke a designation if the Secretary finds that the circumstances that were the basis for the designation have changed in such a manner as to warrant revocation, or if the national security of the United States warrants a revocation.

Figure 3: Number of Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO), 1997

through 2014, by Year of Designation.

State Considered Input from Other Agencies in All FTO Designations between 2012 and 2014

According to State officials and our review of agency documents, State considered information and input provided by other State bureaus and federal agencies for all 13 designations made between 2012 and 2014. State considered this input during the first three steps in its designation process: conducting the equity check, compiling the administrative record, and obtaining approval in the clearance process.

During our review of the 13 FTO designations between 2012 and 2014, officials from the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, and the Treasury, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) reported that State considered their input when making designations. Specifically, we found that State considered information during the first three steps in the FTO designation process, including the following:

- Step 1: Equity check – According to State officials, regional bureaus at State and other agencies provided input to CT during the equity check step by identifying, when warranted, any law enforcement, diplomatic, or intelligence equities that would be jeopardized by the designation of the target organization.[16] Officials from Defense, DHS, Justice, Treasury, and the intelligence community also confirmed that they provided input during the equity check. According to State officials, other bureaus and agencies participating in the equity check included the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Counterterrorism Center, the National Security Agency, and the National Security Council Counterterrorism staff.

- Step 2: Administrative record – Agencies provided classified and unclassified materials to State to support the draft administrative record. For example, officials from ODNI told us they provide an assessment and intelligence review, at the request of State, for any terrorist organization that is nominated for FTO designation. U.S. intelligence agencies may also provide information to State during the equity check and during the compilation of the administrative record to support the designation. Otherwise, State has direct access to the disseminated intelligence of other agencies and does not need to separately request such information, according to CT officials.

- Step 3: Clearance – In accordance with the law, Justice and Treasury review the draft administrative record for legal sufficiency and provide their input to State before the administrative record is finalized. Officials from Treasury and Justice told us that State considered their input during the clearance process for the administrative record for the 13 FTO designations we examined. This consultation culminates in and is documented through letters of concurrence in support of each FTO designation signed by Treasury and Justice. In all 13 FTO designations that we reviewed, Treasury and Justice issued signed letters of concurrence.

U.S. Agencies Impose a Variety of Consequences on Designated FTOs and Associated Individuals

The U.S. government penalizes designated FTOs through three key consequences. First, the designation of an FTO triggers a freeze on any assets the organization holds in a financial institution within the United States. Second, the U.S. government can criminally prosecute individuals that provide material support to an FTO, as well as impose civil penalties. Third, FTO designation imposes immigration restrictions upon members of the organization and individuals that knowingly provide material support or resources to the designated organization. Over the period of our review, we found that U.S. agencies imposed all three consequences.

Blocking of FTO Funds Held in U.S. Financial Institutions

U.S. persons are prohibited from conducting unauthorized transactions or having other dealings with or providing services to designated FTOs. U.S. financial institutions that are aware that they are in possession of or control funds in which an FTO or its agent has an interest must retain possession of or maintain control over the funds and report the existence of such funds to Treasury.[17]

As of December 31, 2013, which is the date for the most recently published Terrorist Assets Report, the U.S. government blocked funds related to 7 of the 59 currently designated foreign terrorist organizations, totaling more than $ 22 million (see Table 1). As of December 2013, there were no blocked funds reported to Treasury related to the remaining 52 designated FTOs. According to Treasury, the reported amounts blocked by the U.S. government change over the years because of several factors, including forfeiture actions, reallocation of assets to another sanctions program, or the release of blocked funds consistent with sanctions policy.

Table 1: Blocked Funds in the United States Related to Designated Foreign

Terrorist Organizations and Persons, as of December 31, 2013

| Foreign terrorist organization | Blocked funds (in U.S. dollars) | |

| al Qaeda | $ 13,503,338 | |

| HAMAS | 1,210,769 | |

| Hizballah | 6,802,767 | |

| Lashkar I Jhangvi | 1,551 | |

| Lashkar-e Tayyiba | 14,890 | |

| Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) | 599,224 | |

| Palestinian Islamic Jihad | 63,828 | |

| Total blocked funds | $ 22,196,367 | |

Funds shown in the table above are blocked by the U.S. government pursuant to terrorism sanctions administered by Treasury, including FTO sanctions regulations and global terrorism sanctions regulations.[18] The FTO-related funds blocked by the United States are only funds held within the United States and do not include any assets and funds that terrorist groups may hold outside U.S. financial institutions. However, according to Treasury officials, while designation of FTOs exposes and isolates individuals and organizations, and denies access to U.S. financial institutions, in some cases, FTOs may also be sanctioned by the United Nations or other international partners, an action that may block access to the global financial system.

Prosecution of Individuals for Providing Support to FTOs

Designation as an FTO triggers criminal liability for persons within the United States or subject to U.S. jurisdiction who knowingly provide, or attempt or conspire to provide, “material support or resources” to a designated FTO.[19] Violations are punishable by a fine and up to 15 years in prison, or life if the death of a person results. Furthermore, it is also a crime to knowingly receive military-type training from or on behalf of an organization designated as an FTO at the time of the training.[20]

Between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013, which is the most recent date for which data are available, over 80 individuals were convicted of terrorism or terrorism-related crimes, that included providing material support or resources to an FTO or receiving military-type training from or on behalf of an FTO. The penalties for these convictions varied, and included some combination of imprisonment, fines, and asset forfeiture.[21] For example, individuals convicted of terrorism or terrorism-related crimes, which included providing material support to an FTO, received sentences that included imprisonment lengths that varied between time served and life in prison, plus 95 years. In addition, sentencing for convicted individuals included fines up to $ 125,000, asset forfeiture up to $ 15 million, and supervised release for up to life.

In addition, Justice may also bring civil forfeiture actions against assets connected to terrorism offenses, including the provision of material support to FTOs.[22] U.S. law authorizes, among other things, the forfeiture of property involved in money laundering, property derived from or used to commit certain foreign crimes, and the proceeds of certain unlawful activities. Once the government establishes that an individual or entity is engaged in terrorism, it may bring forfeiture actions by proceeding directly against the assets (1) of an individual, entity, or organization engaged in planning or perpetrating crimes of terrorism against the United States or U.S. citizens; (2) acquired or maintained by any person intending to support, plan, conduct, or conceal crimes of terrorism against the United States or U.S. citizens; (3) derived from, involved in, or used or intended to be used to commit terrorism against the United States or U.S. citizens or their property; or (4) of any individual, entity, or organization engaged in planning or perpetrating any act of international terrorism. According to Justice officials, there have not been any civil forfeiture actions related to FTOs. However, Justice officials said their department routinely investigates and takes actions against financial institutions operating in the United States that willfully violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. They added that Justice has, for example, imposed fines and forfeitures and installed compliance monitors in cases where banks have violated terrorism-related sanctions programs. Furthermore, according to Justice officials, there are numerous other investigative and prosecutorial tools available to the United States to confront terrorism and terrorism-related conduct, disrupt terrorist plots, and dismantle foreign terrorist organizations.[23]

Enforcement of Immigration Actions for FTO Support

FTO representatives and members, as well as individuals who knowingly provide material support or resources to a designated organization who are not U.S. citizens are inadmissible to, and in some cases removable from, the United States under the Immigration and Nationality Act.[24] However, exemptions or waivers can be granted for certain circumstances, according to State and DHS officials.[25] For example, DHS may grant eligible individuals exemptions in cases where material support was provided under duress. Individuals found inadmissible or deportable without an appropriate waiver or exemption under these provisions are also barred from receiving most immigration benefits or relief from removal. State and DHS are responsible for enforcing different aspects of the immigration restrictions and ensuring that inadmissible individuals without an appropriate waiver or exemption do not enter the United States.

State consular officers at U.S. embassies and consulates are responsible for determining whether an applicant is eligible for a visa to travel to the United States. In instances where a consular officer determines that an applicant has engaged or engages in terrorism-related activity, the visa will be denied.[26] According to State Bureau of Consular Affairs data, between fiscal years 2009 and 2013, which was the most recent period for which data are available, 1,069 individuals were denied nonimmigrant visas and 187 individuals were denied immigrant visas on the basis of involvement in terrorist activities and associations with terrorist organizations.[27]

DHS develops and deploys resources to detect; assess; and, if necessary, mitigate the risk posed by travelers during the international air travel process, including when an individual applies for U.S. travel documents; reserves, books, or purchases an airline ticket; checks in at an airport; travels en route on an airplane; and arrives at a U.S. port of entry. For example, upon arrival in the United States, all travelers are subjected to an inspection by U.S. Customs and Border Protection to determine if the individual is eligible for admission under U.S. immigration law. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data, between fiscal years 2009 and 2014, which was the most recent period for which data were available, more than 1,000 individuals were denied admission to the United States for various reasons, and were identified for potential connections to terrorism or terrorist groups, including being a member of or supporting an FTO. In addition, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is responsible for deporting individuals determined to be engaged in terrorism or terrorism-related activities. Between fiscal years 2013 and 2104, which was the most recent period for which data are available, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials indicated that 3 individuals determined to be associated with or to have provided material support to designated FTOs were removed from the United States.

Further, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is responsible for the adjudication of immigration benefits. An individual who is a member of a terrorist organization or who has engaged or engages in terrorist-related activity, as defined by the Immigration and Nationality Act, is deemed inadmissible to the United States and is ineligible for most immigration benefits.[28] The law grants both the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Homeland Security unreviewable discretion to waive the inadmissibility of certain individuals who would be otherwise inadmissible under this provision, after consulting with each other and the Attorney General.[29]

Additionally, according to DHS officials, an exemption may be applied to certain terrorist-related inadmissibility grounds if the activity was carried out under duress, or under certain circumstances, such as the provision of material support in the form of medical care. Such exemptions, if applied favorably, may allow an immigration benefit to be granted. DHS officials stated that these exemptions are extremely limited.

Concluding Observations

Terrorist groups, such as al Qaeda and its affiliates, Boko Haram, and ISIL, continue to be a threat to the United States and its foreign partners. The designation of FTOs, which can result in civil and criminal penalties, is an integral component of the U.S. government’s counterterrorism efforts. State’s process for designating FTOs considers input and information from several key U.S. agency stakeholders, and allows U.S. agencies to impose consequences on the organizations and individuals that associate with or provide material support to FTOs. Such consequences help U.S. counterterrorism efforts isolate terrorist organizations internationally and limit support and contributions to those organizations.

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided draft copies of this report to the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, State, and the Treasury, as well as the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, for review and comment. The Department of Homeland Security provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. The Departments of Defense, Justice, State, and the Treasury, as well as the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, had no comments.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7331 or johnsoncm@gao.gov. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Charles Michael Johnson, Jr. Director, International Affairs & Trade

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

This report examines the Department of State’s (State) process for designating foreign terrorist organizations (FTO) and the consequences resulting from designation. We report on (1) the process for designating FTOs, (2) the extent to which the State considers input from other agencies during the FTO designation process, and (3) the consequences that U.S. agencies impose as a result of an FTO designation.

To identify the steps in the FTO designation process, we reviewed the legal requirements for designation and the legal authorities granted to State and other U.S. agencies to designate FTOs. In addition, we reviewed State documents that identified and outlined State’s process to designate an FTO, from the equity check through publishing the designation in the Federal Register. We interviewed State officials in the Bureau of Counterterrorism to confirm and clarify the steps in the FTO designation process and to identify which agencies are involved in the process and at what steps they are involved. We also interviewed officials from the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice (Justice), and the Treasury (Treasury), as well as officials from the intelligence community, to determine each agency’s level of participation in the process.

To assess the extent to which State considered information from other agencies in the designation process, we interviewed officials from the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, State, and the Treasury, as well as officials from the intelligence community, to determine when information is provided to State on organizations considered for FTO designation, as well as the nature of that information. We defined consideration as any action of State to request, obtain, and use information from other agencies, as well as letters of concurrence from those agencies. We reviewed both Justice’s and Treasury’s letters of concurrence for all 13 designations made between 2012 and 2014. We also interviewed State officials to determine how information provided by other agencies is considered during the FTO designation process.

To identify the consequences U.S. agencies impose as a result of FTO designation, we reviewed the legal consequences agencies can impose under U.S. law, including the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended. Specifically, we reviewed the FTO funds and assets related to FTOs that are blocked by U.S. financial institutions, as reported by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the Department of the Treasury. We reviewed the publicly available Terrorist Assets Reports published by Treasury for calendar years 2008 through 2013, which identify the blocked assets identified and reported to Treasury related to FTOs, as well as organizations designated under additional Treasury authorities. U.S. persons are prohibited from conducting unauthorized transactions or having other dealings with or providing services to the designated individuals or entities. Any property or property interest of a designated person that comes within the United States or into the possession or control of a U.S. person is blocked and must be reported to OFAC. The Terrorist Assets Reports identify these reported blocked assets held within U.S. financial institutions that are targeted with sanctions under any of the three OFAC-administered sanctions programs related to terrorist organizations designated as FTOs, specially designated global terrorists, and specially designated terrorists under various U.S. authorities. We verified the totals reported in each of the reports and identified the funds blocked for organizations designated as FTOs. We also interviewed Treasury officials to discuss the reports of blocked assets and the changes in the assets across years. We did not analyze blocked funds for organizations that were designated under other authorities or by the United Nations or international partners. To assess the reliability of Treasury data on blocked funds, we performed checks of the year-to-year data published in the Terrorist Assets Reports for inconsistencies and errors. When we found minor inconsistencies, we discussed them with relevant agency officials and clarified the reporting data before finalizing our analysis. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report.

We also reviewed the Department of Justice National Security Division Chart of Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism Related Convictions to identify the individuals convicted of and sentenced for providing material support or resources to an FTO or receiving military-type training from or on behalf of an FTO between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013, which was the period for which the most recent data were available. Designation as an FTO introduces the possibility of a range of civil penalties for the FTO or its members, as well as criminal liability for individuals engaged in certain prohibited activities, such as individuals who knowingly provide, or attempt or conspire to provide, “material support or resources” to a designated FTO. We reviewed Justice data of only public/unsealed convictions from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2013. For the purposes of our report, we analyzed the Justice data on the convictions and sentencing associated with individuals who were convicted of knowingly providing, or attempting or conspiring to provide, “material support or resources” to a designated FTO. We also reviewed the data to identify the individuals who were convicted of knowingly receiving military-type training from or on behalf of an organization designated as an FTO at the time of the training. The data did not include defendants who were charged with terrorism or terrorism-related offenses but had not been convicted either at trial or by guilty plea, as of December 31, 2013. The data included defendants who were determined by prosecutors in Justice’s National Security Division Counterterrorism Section to have a connection to international terrorism, even if they were not charged with a terrorism offense. To assess the reliability of the convictions data, we performed basic reasonableness checks on the data and interviewed relevant agency officials to discuss the convictions and sentencing data. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report.

To identify the immigration restrictions and penalties imposed on individuals associated with or who provided material support to a designated foreign terrorist organization, we analyzed available data from State Bureau of Consular Affairs reports on visa denials between fiscal years 2009 and 2013, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection enforcement system database on arrival inadmissibility determinations between fiscal years 2009 and 2014, and information from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement on deportations between fiscal years 2013 and 2014. The Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended, establishes the types of visas available for travel to the United States and what conditions must be met before an applicant can be issued a particular type of visa and granted admission to the United States. For the purposes of this report, we primarily included the applicants deemed inadmissible under section 212(a)(3) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which includes ineligibility based on terrorism grounds. We did not include the national security inadmissibility codes that were not relevant to terrorism. In each instance, we analyzed the data provided by the agencies and performed basic checks to determine the reasonableness of the data. We also spoke with relevant agency officials to discuss the data to confirm the reasonableness of the totals presented for individuals denied visas, denied entry into the United States, or deported from the United States for association with a designated foreign terrorist organization. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2015 to June 2015 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Agencies and Their Roles in the Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) Designation Process

| Organization | Relevant component | Role in FTO process |

| Department of Defense | Office of the Secretary of Defense | Provides input during equity check |

| Department of Homeland Security | Office of Policy | Provides input during equity check |

| U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services | Adjudicates immigration benefits | |

| U.S. Customs and Border Protection | Determines eligibility for admission at U.S. border | |

| U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement | Enforces immigration restrictions | |

| Intelligence community | Central Intelligence Agency | Provides input during equity check |

| National Counterterrorism Center | Provides input during equity check | |

| National Security Agency | Provides input during equity check | |

| Department of Justice | Federal Bureau of Investigation | Provides input during equity check |

| National Security Division | Consultative partner in FTO designations and prosecutes individuals for FTO-related offenses | |

| National Security Council | National Security Council Counterterrorism staff | Provides input during equity check |

Department of State

| Bureau of Counterterrorism | Leads FTO designation process |

| Consular Affairs | Adjudicates visa applications | |

| Office of the Legal Adviser | Reviews the administrative record | |

| Relevant regional bureaus | Provide input during equity check | |

| Department of the Treasury | Office of Foreign Assets Control | Consultative partner in FTO designations and blocks assets of FTOs |

Source: GAO analysis of agency documents and interviews. | GAO-15-629

Note: The Secretary of State is required by law to consult with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Attorney General during the foreign terrorist organization designation process. Other interagency consultations occur as a matter of Department of State policy.

Appendix III: Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, as of December 31, 2014

| Organization | Date designated | |

| 1. | Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) | 10/8/1997 |

| 2. | Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) | 10/8/1997 |

| 3. | Aum Shinrikyo (AUM) | 10/8/1997 |

| 4. | Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) | 10/8/1997 |

| 5. | Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group) (IG) | 10/8/1997 |

| 6. | Hamas | 10/8/1997 |

| 7. | Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) | 10/8/1997 |

| 8. | Hizballah | 10/8/1997 |

| 9. | Kahane Chai (Kach) | 10/8/1997 |

| 10. | Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) (Kongra-Gel) | 10/8/1997 |

| 11. | Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) | 10/8/1997 |

| 12. | National Liberation Army (ELN) | 10/8/1997 |

| 13. | Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) | 10/8/1997 |

| 14. | Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) | 10/8/1997 |

| 15. | PFLP-General Command (PFLP-GC) | 10/8/1997 |

| 16. | Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLF) | 10/8/1997 |

| 17. | Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) | 10/8/1997 |

| 18. | Revolutionary Organization 17 November (17N) | 10/8/1997 |

| 19. | Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) | 10/8/1997 |

| 20. | Shining Path (SL) | 10/8/1997 |

| 21. | al Qaeda (AQ) | 10/8/1999 |

| 22. | Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) | 9/25/2000 |

| 23. | Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA) | 5/16/2001 |

| 24. | Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) | 12/26/2001 |

| 25. | Lashkar-e Tayyiba (LeT) | 12/26/2001 |

| 26. | Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade (AAMB) | 3/27/2002 |

| 27. | al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) | 3/27/2002 |

| 28. | Asbat al-Ansar (AAA) | 3/27/2002 |

| 29. | Communist Party of the Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) | 8/9/2002 |

| 30. | Jemaah Islamiya (JI) | 10/23/2002 |

| 31. | Lashkar i Jhangvi (LJ) | 1/30/2003 |

| 32. | Ansar al-Islam (AAI) | 3/22/2004 |

| 33. | Continuity Irish Republican Army (CIRA) | 7/13/2004 |

| 34. | Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (formerly al Qaeda in Iraq) | 12/17/2004 |

| 35. | Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) | 12/17/2004 |

| 36. | Islamic Jihad Union (IJU) | 6/15/2005 |

| 37. | Harakat ul-Jihad-i-Islami/Bangladesh (HUJI-B) | 3/5/2008 |

| 38. | al-Shabaab | 3/18/2008 |

| 39. | Revolutionary Struggle (RS) | 5/18/2009 |

| 40. | Kata’ib Hizballah (KH) | 7/2/2009 |

| 41. | al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) | 1/19/2010 |

| 42. | Harakat ul-Jihad-i-Islami (HUJI) | 8/6/2010 |

| 43. | Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) | 9/1/2010 |

| 44. | Jundallah | 11/4/2010 |

| 45. | Army of Islam (AOI) | 5/23/2011 |

| 46. | Indian Mujahedeen (IM) | 9/19/2011 |

| 47. | Jemaah Anshorut Tauhid (JAT) | 3/13/2012 |

| 48. | Abdallah Azzam Brigades (AAB) | 5/30/2012 |

| 49. | Haqqani Network (HQN) | 9/19/2012 |

| 50. | Ansar al-Dine (AAD) | 3/22/2013 |

| 51. | Ansaru | 11/14/2013 |

| 52. | Boko Haram | 11/14/2013 |

| 53. | al-Mulathamun Battalion | 12/19/2013 |

| 54. | Ansar al-Shari’a in Benghazi | 1/13/2014 |

| 55. | Ansar al-Shari’a in Darnah | 1/13/2014 |

| 56. | Ansar al-Shari’a in Tunisia | 1/13/2014 |

| 57. | Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis | 4/10/2014 |

| 58. | al-Nusrah Front | 5/15/2014 |

| 59. | Mujahidin Shura Council in the Environs of Jerusalem (MSC) | 8/20/2014 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of State information. | GAO-15-629

Appendix IV: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

GAO Contacts

Charles Michael Johnson, Jr., (202) 512-7331 or johnsoncm@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact listed above, Elizabeth Repko (Assistant Director), Claude Adrien, John F. Miller, and Laurani Singh made key contributions to this report. Ashley Alley, Martin de Alteriis, Tina Cheng, and Lynn Cothern provided technical assistance.