Defence Institution Building in Ukraine at Peace and at War

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 17, Issue 3, p.92-108 (2018)Keywords:

cooperation, Defense Institution Building, defense reform, mobilization, peacekeeping, professionalization, UkraineAbstract:

There are two distinct periods in Defense Institution Building in Ukraine since gaining independence in 1991. A period of peace until February 2014, and the period of war with Russia in 2014-2018. In the pre-war period of 1991-2013, the economic problems, inconsistencies in national strategy and consequent neglect of national defense requirements led to unclear military strategies and declarative rather than substantial reforms of the Armed Forces. Ukraine was trying to compensate the impact of its economic weakness and policy inconsistencies on defense through active cooperation with NATO and participation in peacekeeping operations under the auspices of the UN, NATO and the EU. However, in the spring of 2014, the response of Ukraine exposed serious weaknesses in all defense aspects except for the people’s will to defend the country. Responding to the Russian annexation of Crimea and the invasion to the South-Eastern Ukraine, Ukraine has mobilized, equipped, and trained a substantial military force of 250 000 active personnel and invested substantial resources in building effective military with agile professional active component supported by deployable ready reserve, jointly capable to deter possible aggression from Russia.

Introduction

In 1991, independent Ukraine inherited from the Soviet Union sizeable conventional military contingent equivalent to Europe’s second largest armed forces and had on its territory the third world largest nuclear arsenal.[1] The process of conversion of this rather chaotic massive post-Soviet force and building the coherent national military of Ukraine went through two major stages – peace-time decline (1991-2013) and war-time transformation since the start of Russian invasion to Crimea in 2014.

Initial hesitation in foreign policy and security orientation led to the lack of clarity in defense policy and inconsistency between ambitious political declarations and scarce appropriated resources. Ambitious goals of building professional military, introduction of interoperability with NATO, modernization of armaments and active contribution to peacekeeping operations were never adequately supported by resources.

As a result, at the start of the Russian military aggression in February 2014, Ukraine had little to effectively resist with militarily. Nevertheless, in 2018, four years after the start of invasion, Ukraine managed to mobilize and equip substantial force much more capable to deter invasion from Russia. Having clarified its defense policy under the pressure of real hostile conditions, Ukraine is building national defense utilizing its own combat experience, activating cooperation with leading democracies of the West and applying their best practices.

This article will offer a glance at Ukrainian military posture in the period preceding the Russian aggression in 2014, key developments during hostilities in Crimea and Donbas regions of Ukraine in 2014-2018 and prospects for building the future Ukrainian military.

Peacetime Defense Institution Building in Ukraine from Independence in 1991 until the Russian Aggression in 2014

The Ukrainian leadership of the early 1990s, impressed by the mere size of its military heritage and deceived by the international security environment after the collapse of the Soviet Union, adopted the strategy of non-alignment. The first officially adopted Military Doctrine (1993) at the start of the period read:

Ukraine links the reduction and elimination of nuclear weapons located on its territory with the adequate actions of other nuclear states and the granting by them and the world community reliable guarantees of its security.[2]

The following year, in December 1994, such thinking was embedded in the so-called Budapest Memorandum. The full name of the document is Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Ukraine’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. It was signed on 5 December 1994 by the Presidents of Ukraine, the Russian Federation and the United States of America, and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.[3]

Ukraine was free to see things this way, but in practical terms not much resulted from Ukraine’s reliance on adequate actions and reliable guarantees “of other nuclear states.” Under the joint pressure from the US and Russia Ukraine agreed to remove nuclear weapon in exchange for about $ 1 billion worth of support from the US under the Cooperative Threat Reduction program, certain amount of Russian fuel for Ukrainian nuclear power stations, and paper-worth security assurances from Russia, the US and other nuclear powers under the Budapest Memorandum.[4]

After Ukraine’s submitting to nuclear disarmament and signing the Budapest Memorandum at the end of 1994, the following period can be identified as the peacetime building of Ukrainian Armed Forces. Since 1995 and until the end of 2013 it can best be characterized by the following key developments: development of consecutive programs of the Armed Forces reform; active cooperation with NATO; peacekeeping duties in the Balkans, Africa, Iraq and Afghanistan; and efforts for the Armed Forces’ “professionalization.”

Peacetime Defense Reform Programs

The middle term defense planning documents had to provide necessary link between required capabilities and resources. This chain of programs (Box 1) is highlighting the many rather unsuccessful attempts of transformation of post-Soviet military inherited by Ukraine. Some of the documents where more substanti-

Box 1: Programs of Reform and Development of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (1991-2013)

|

ated, some less, but they all were declarative, because at this period the programs of reforms were never supported by required resources.

For instance, the first national defense reform program, “The State Program of Armed Forces Construction and Development by 2005” (1997), was looking not so much as coherent document but more like a list of noble intentions and anticipated military personnel of 450 000. The next one, “The State Program of Armed Forces of Ukraine Reform and Development by 2005,” adopted in 2000, represented an upgrade of the earlier program approved in 1997 and slightly reduced the desired strength to 375 000.

Nevertheless, the country was unable to sustain the anticipated force level. Very modest estimates at that time suggested that, in accordance with standard requirements, the armed forces even reduced to strength of 300 000 military personnel, over 3 000 tanks, and over 500 aircraft needed around US$5-6 billion to maintain their readiness. However, the Ukrainian state budget of that time regularly allocated only fraction of this requirement. In early 2000s, it was universally recognized that further reductions of the military almost by half (to less than 200 000) were imminent. Besides, military conscription, even reduced from the Soviet two years to just one year in Ukraine, became universally unpopular among Ukrainian citizens, and the quality of recruits visibly declined. Most of military personnel consisted of unmotivated soldiers and demoralized by poor social conditions junior and middle ranking officers, while top military leadership started looking at the institution as a source of patronage and rent-seeking revenue thus copying their corrupt civilian top masters.

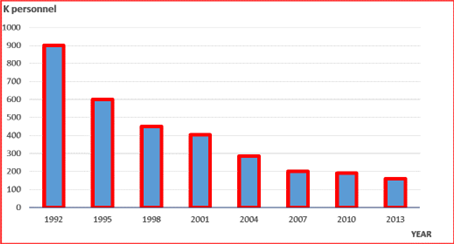

For all the reasons indicated above, and in spite of the best intentions of the MOD and the General Staff planners, the mere result of their efforts in the whole period of 1991-2013 looked like continuous reduction of the number of military personnel (see Figure 1.).

The promising political turn after the victory of the “Orange Revolution” was supported by elaborated new defense reform document –“Program for the Armed Forces Reform and Development for the Period of 2006-2011” (approved in 2005). This Program included: transition of command and control system to NATO standards; shift from four to three military services by unifying the Air Forces and Air Defense Forces into a single Air Force; providing for the jointness of different services by establishing Joint Operations Command; introduction of the Western approaches to military education, combat training and personnel management. However, the planners still had to prioritize limited resources. In accordance with their functional responsibilities the Armed Forces were structured into Joint Rapid Reaction Forces (JRRF), Main Defense Forces (MDF) and otherformations (logistics, communications, etc.) subordinated directly to the General Staff. Given the unfavorable financial situation, such functional structure allowed to spend limited resources more effectively and enhance the combat readiness of the Armed Forces. It still had to agree on some differences between JRRF and MDF. Flight hours, training hours in the field, sailing days for ships, etc., were different.

Nevertheless, it looked like sizeable improvement in defense planning and received favorable comments from NATO. It should be mentioned that in a few years preceding the approval of this Program in 2005, Ukraine announced its intention to become NATO member in the future and significantly intensified its

Figure 1: Personnel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (1995-2914).

cooperation programs under the NATO Partnership for Peace Program. Earlier intensive bilateral cooperative programs with the USA, the UK, Canada, France, Germany and other countries were augmented with establishing in country advisory missions by the UK (special defense advisor to the Ministry of Defense), Germany (adviser on human resource management), France (professional education and peacekeeping), while the USA already had Security Assistance Mission in Ukraine for several years. In addition to the more active bilateral programs, much more extensive partnership programs were offered by NATO Headquarters in the area of combat training and education, as well as by the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces in the area of democratic governance of the security sector.

This cooperation offered for Ukrainians the chance to learn modern concepts of jointness, democratic civilian control, defense resource management, and provided specific financial and advisory support from friendly countries of the democratic West.

However, this Program was not implemented either, in spite of much greater utilization of Western advisory support and applying NATO best practices. Similar to the cases of previous peacetime defense reform programs, it was never supported with required resources (See Table 1).

Nevertheless, developments surrounding the adoption and implementation of this Program proved that, given clear political course and political-military guidance, Ukrainians were capable to narrow considerably their traditional gap between political declarations to join NATO and security and resource realities.

The principle document for NATO-Ukraine cooperation is the Charter on a Distinctive Partnership signed in 1997. It stipulated the principles, the scope, and the mechanisms of cooperation. The Charter paved the way to establishing the key institutions for coordinating defense and security cooperation: The Joint Working Group on Defense Reform and NATO Liaison Office. Overall, Ukraine-NATO relations in this period benefited from various mechanisms like, for instance, Planning and Review Process (PARP) serving as a real mechanism of achieving interoperability between Ukrainian military and NATO militaries. However, the quantity and intensity of security cooperation typically was falling victim to political and economic processes in Ukraine.

Table 1: Arms Procurement Budget for the State Program 2006-2011, mln. UAH.

YEAR | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

Planned | 232.5 | 1135.3 | 605.9 | 2342.3 | 4961.0 |

Actual | 161.2 | 682.0 | 587.4 | 486.0 | 2140.5 |

Participation in NATO-led operations (KFOR, ISAF, OAE, NTM) provided Ukrainian troops and personnel with the first-hand experience at the expense of NATO, but also, in some operations it provided Ukraine with the opportunity to pay for its own deployed personnel and in such way to learn what is the real cost of contribution to international peace and security. This is contrary to the UN missions, where expenses were covered from the UN budget.

Over the period from 1992 until 2014, more than 40 000 Ukrainian peacekeepers took part in the international peacekeeping and security operations in Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Eastern Slavonia, Angola, Macedonia, Guatemala, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, the Prevlaka peninsula in Croatia, Kuwait, Sierra Leone, in Georgia, Moldova (Transnistria), Iraq, Lebanon, Ethiopia and Eritrea, Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo and other countries. Ukrainian peacekeepers served in the UN, NATO, EU, OSCE and regional (Transnistria) missions and operations. In these peacekeeping operations, 53 Ukrainian peacekeepers were killed.[5]

“Professionalization” Plans

In an evident attempt to put a good face on the continuous reduction of Ukraine’s military, the political leadership of the country responded to the dominant expectations of Ukrainian people and announced the policy course for transitioning from general military conscription to volunteer manning of the Armed Forces. Consequent efforts of “professionalization” took the shape of continuous but generally unsuccessful efforts of building the all-volunteer Armed Forces, because these decisions became traditionally based on economic and populist considerations, rather than on sober threat and resource analysis (see Box 2).

The first such program, approved by the President Leonid Kuchma in 2002, anticipated that Ukraine was to have a smaller, 180 thousand strong volunteer force by 2015. More so, in 2005, emboldened by the victory of “Orange Revolution” and high people’s trust, the country’s leadership decided to expedite the integration to NATO and further reduce the period of transition to all volunteer force to 2010. At some point during the 2007 parliamentary elections campaign, presidential candidate (former Prime Minister of Ukraine) Yuliya Tymoshenko even dared to promise transition to volunteer force already in 2008. In both instances, that did not work. Meanwhile, the economic crisis of 2009-2010 and Russian invasion to Georgia decreased the populism and forced Ukraine to postpone both reduction in numbers and transition to an all-volunteer force.

Box 2. Key documents on “professionalization” of the Armed Forces of Ukraine

|

However, in the later period of 2010-2013, the post of the President of Ukraine was occupied by the pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych. In that period many previously initiated pro-Western reforms were immediately reversed: The Joint Operations Command was quickly disbanded; personnel management reforms negated; cooperative programs with Western companies in shipbuilding were cancelled in favor of presumably less expensive Russian suppliers, etc. The only course, which remained intact, was the transition to all-volunteer force though at further reduced size of 100 000 by 2017 (Box 1), while substantiation for this stage was different. It was based on the premise by Yanukovych administration that Ukraine did not face any real military threat, which allegedly allowed for further reduction of the numbers below 100 000 (from initial personnel strength of over 800 000 in 1991) thus raising the salaries to competitive levels and making the recruitment process effective. For evident reason of Russian aggression, this plan was not materialized either, and Ukraine still preserves the outdated conscription, though putting more and more emphasis on rapid reaction units manned by volunteers and reservists.

Developments during Hostilities in Crimea and Donbas Regions of Ukraine in 2014-2018. Prospects for Building Future Ukrainian Military

The generally pro-Russian political course of the Yanukovych political leadership led to transformation of Ukrainian military from underfunded and undertrained, but still equipped and sizeable force to symbolic institution consisting of skeleton units expected to carry limited missions of localization of border conflicts, peacekeeping and support to civilian authorities, rather than containment or repelling a full-sized military aggression by an aggressive neighboring country like Russia.

In February 2014, when the pro-Russian dictatorial President Viktor Yanukovych fled from Kyiv, the Ukrainian military looked much less impressive than it had been in 1991. Since 1991, the quantity of military equipment had dropped by about five times, while the state of its readiness was below minimal requirements. Sizeable defense industry of Ukraine having very small internal defense order mostly survived implementing foreign orders. Typical Western accounts of that period indicated that the total number of usable troops and equipment in Ukrainian land forces amounted nominally to 80 000 personnel, 775 tanks, 51 helicopters, fewer than 1 000 artillery pieces and 2 280 armored personnel carriers.[7]

Ukraine’s first reaction to the Russian “hybrid” actions in Crimea was to keep its bases for as long as possible, tying down Russian forces in the peninsula while putting maximum effort into the mobilization of reserves and into organizing the deployment of land forces closer to the Russian border in the East. Ukrainian troops in Crimea, however, ceased to resist after three weeks, having lost half of the navy ships and about 50 aircraft, captured by the Russians at Belbeck airfield. About 12 000 military personnel, mostly locally enlisted, shifted sides in favor of Russia.

To significant extent, this was a result of the previously mentioned personnel policy gap between populist intentions to build fully professional military and miniscule resources provided to that end. Consequently, “non-expensive” local military contract servicemen from Crimea provided the largest number of traitors.

Transition during the War

Soon after the loss of Crimea, in April 2014, Ukrainian troops were engaged by armed pro-Russian separatists and Russian mercenaries. In response, Ukrainians have chosen to fight against Russian invading force and pro-Russian insurgency, losing part of Ukraine’s territory but securing freedom. Besides, Ukraine took continuous efforts to build up its military, which had two major simultaneous missions: to deter Russia from a full-scale invasion and to restore control over Donetsk and Lugansk regions (the only places where the separatists had been successful). The key problems of the military at the initial months were to organize mobilized units for effective military actions against an armed insurgency—and possible regular Russian troops—and to provide them with the basic military equipment needed.[8] By the end of summer 2014, forward deployed troops in Donbas found themselves engaged in fighting regular Russian troops, while the Ministry of Defense management system was overwhelmed with issues of mobilization, organization, motivation and provision of social support.

Yet, over the course of the first year of the war, the Armed Forces managed to mobilize, equip, and train substantial forces. Ukraine has gone from having an army of approximately 130 000 with almost no ready units, to having a force of over 200 000 – of which approximately one third part were deployed to deter potential Russian aggression and to eliminate separatist insurgency. Summarily, over the first year of war, Ukraine has mobilized and equipped over 250 thousand personnel, looking more capable to deter invading Russian forces.

Naturally, at the start of aggression, Ukrainians expected and requested immediate support from signatories of the Budapest Memorandum and other friendly countries in the West. However, in the spring-summer period of 2014, Western leadership hesitated to offer any meaningful supplies beyond very simple basic materiel. Most of Ukraine’s possible supporters in NATO and the EU were not ready to support Ukraine militarily without a clear leadership by the United States.

Having to defend itself on its own, Ukraine had to utilize quickly available human potential of reservists and volunteers in order to win time for reconstitution of the military. This supplement took the form of “territorial defense” battalions under the Ministry of Defense and “volunteer” police and National Guard battalions under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Besides, the ordinary citizens of Ukraine organized variety of logistical, financial and medical support networks in the interests of the military.

On this battlefield, Ukrainian land forces opposed Russian-led mixture of regular Russian land forces and pro-Russian proxies. Both sides primarily used old Soviet platforms modernized and better supported to increase their ranges, lethality and accuracy. Despite initial, total Russian technological domination in most conventional weapons systems, primarily in aerial reconnaissance, electronic warfare and secure communication, in a short period of time Ukrainian military, with some support from Western partners and local volunteers, quickly reduced the technological dis-balance. Both sides equally resorted to the use of high-tech drones, modern observation, communications, targeting and electronic warfare equipment on the scale never seen before.

Russians were successful only in one area, denying Ukrainians their Close Air Support (CAS) through advanced short-range air defense systems and stronger intelligence. Ukraine could not adopt quickly its Soviet era fleet of combat aircraft and helicopters and decided to stop using the CAS. Ukrainian airplanes and helicopters employed without proper anti-air defense systems appeared to be too vulnerable even if sometimes equipped with thermal and optical protection devices. In 2014, when Ukrainians used aviation in support of combat actions, they lost nine combat aircraft, three transport aircraft and ten helicopters.[9]

In this war, Russians used the opportunity to test many new prototypes of drones like Orlan, Zastava, Grusha, Granat, Eleron, Takhion; electronic warfare systems Krasukha, Zhitel, Leer, Borisoglebsk, Rtut’ and Dziudoist; target acquisition radars Aistionok, Kredo and Malahit; flame throwers – multiple rocket launchers Tornado, Buratino and portable Shmel, short range air defense systems Verba and Pantsir, and other new designs.

The Ukrainian side did not have time and money to produce so many new national designs, so it placed more emphasis on modernizing available artillery, tanks, fighting vehicles and personnel carriers, and on developing techniques for accurate counterbattery fire, for long-range tank fire, snipers etc. Ukraine initially imported or received as foreign aid some Western drones, as well as target acquisition and communications equipment, but later turned to rely more on nationally developed armaments for its Land Forces and even for air defense. However, it was still in great need of modern foreign armaments, like ATGM “Javelin” supplied by the US in 2018, to say nothing about the need for variety of weapons to revitalize its Navy mostly lost in Crimea.

Both sides paid significant attention to psychological operations (PSYOPS). Today, already known CNN-effect is multiplied by Facebook-effect, mobile-phone effect, Tweeter-effect etc. The war proved that all modern electronic devices and social networks could be used to facilitate spreading rumors, false messages and fake news, as well as to collect personal information on the enemy troops, target acquisition and other intelligence. Russian initial domination in electronic warfare systems also played to a great advantage of the aggressor’s PSYOPS.

Ukraine has mobilized all the available capacities of its defense industry, but it could not fully rearm the armed forces on its own. Provision of the army with state-of-the-art military equipment and weapon systems and creation of stockpiles of missiles and ammunitions, e.g. covering all existing gaps in armaments, required time and resources, which the country lacked. A major Russian assault was still on the agenda.

Countering superior numbers of Russian combat aircraft, combat helicopters (Russia has about six times as many combat aircraft and about three times as many combat helicopters) and tactical missiles would logically require a strong emphasis on different air defense assets and on electronic warfare capability. For this purpose, Ukraine had to look into the experience of neighboring countries like Poland, Romania or Turkey, who demonstrated success in defense industrial production either under licenses, or in close cooperation with major Western weapon producers. This became especially important, since past cooperation with Russia was not an option any more for obvious reasons.

The first year of the involvement of Ukraine’s Armed Forces and other military formations in antiterrorist operation (АТО) in Southern Donbas saw transition from the initial counterinsurgency warfare to classic land operations of the Ukrainian military against pro-Russian separatists, mercenaries and about 7 000-8 000 Russian regular troops, i.e., the ATO actually evolved into a local military conflict. The heroism and sacrifice of Ukrainian military personnel and civilian volunteers, economic and financial pressure of Ukraine’s foreign partners eventually forced Russian President Vladimir Putin to agree to a ceasefire in Minsk, since Russia’s political, economic and human losses became all too evident for everyone.

It appeared that at the tactical level, discipline and motivation of Ukrainians may win over better equipped but less motivated Russian-proxy force. In 2015-2016, all battalion-size attempts from Russians to push Ukrainians from their positions failed, while Ukrainian troops slowly but steadily pushed Russians towards the Minsk agreements’ designated line of separation, which Russians crossed in 2014 and early 2015.

In 2016-2018, after the war has turned from maneuver to trench warfare, Russian typical activities were actions by small sabotage groups and snipers, and continuous indiscriminate artillery fire at both Ukrainian fortifications and civilian populated areas across the frontline. For Ukrainian artillery, it is prohibited to fire at the residential areas, and Russians use this fact placing their own artillery between civilian households on their side. This required Ukrainian troops to look for the ways to improve its reconnaissance, strike precision and quick reaction capabilities.

This latter specific urban-related feature at the tactical level of war is just one of the characteristic signs of the larger, operational, trend of the land warfare – growing impact of the factor of urban terrain. The long trend of increasing ranges and lethality of anti-armor and counter-battery fire in this war quickly led to a situation, when all movements in the open terrain were at great risk of being detected and destroyed. Therefore, both opposing sides had either to dig deep and build fortifications, or place their positions in the abundant residential and industrial areas, which either naturally reduced the risk of destruction by limiting direct targeting, or denied shooting due to humanitarian considerations. Like in coalition operations in Iraq, this factor of urban terrain noticeably reduced the role of advanced technologies on the grounds of either denial by physical obstacles or considerations of political, economic and humanitarian nature.

Another important lesson of the war called for improving the system of reserve force maintenance, especially the mobilization process, and for developing territorial defense strategies as an asymmetric way of employing motivated personnel, inexpensive weapons and better human intelligence against a superior occupying force. To that end, experts often named Finland, the Baltic States, Israel or even Switzerland as a source of useful experience. In concert with substantial numbers of highly trained and equipped Special Forces, this approach seemed like a cost-effective way to neutralize the ‘hybrid’ type of invasion of illegal armed formations supported by regular military units that Russia has deployed.

Overall, in the course of the four years of war, the strength of Ukraine’s Armed Forces was steadily growing despite pitiful mistakes and initial forced retreats. The lessons learned from this war played a key role in devising the plans for Ukraine’s defense institution building.

Plans for the Future

Defense transformation in the wartime naturally required substantial resources both to support the ongoing operations and to build reliable reserves. Consequently, already the 2015 state budget on security and defense was increased to about $5 bln.[10] This was equivalent to 5 percent of the GDP where 3 percent ($3 bln.) had to be appropriated for the military. It allowed building new structures like Special Operations Forces, Airborne-Assault Troops, Marine Command, etc., as well as producing, modernizing and purchasing an array of arms and ammunition. In the later years, the growing economy of Ukraine provided the military with higher absolute budget volumes.

The prolongation of the war with Russia’ supported separatists required from Ukraine more sound and systemic conceptualization for building national defense. Initial delays in developing the coherent plan for reforms likely produced doubts in the political leadership either in the ability or commitment of the military establishment to initiate transformations. Declarations by the Ministry of Defense to “radically change the philosophy of military management” and to create a more effective system that would remove functional duplications between the ministry and the General Staff and embrace international standards and practices in practical terms translated in amendments to the state budget and not much else. In 2015, these doubts might have caused the initiative by the presidential administration to invite the RAND Corporation to conduct a review of Ukrainian defense sector and to make recommendations for needed reforms. The RAND accomplished this request and produced a report, which in its military component recommended measures similar to the above-mentioned earlier document (NATO-oriented but never implemented) Program of Reform and Development of the Armed Forces for 2006-2011. It called for restoration of the Joint Operations Command and other reforms aimed to increase effectiveness of the active military and reserves by moving to all-volunteer force instead of conscription, and improving the system of pay in the ministry to become competitive for qualified civil servants. Besides, RAND recommended radical reforms in the system of democratic civilian control over the military – civilian minister of defense and his/her deputy, integrated defense headquarter instead of the separated ministry and the General Staff, etc.

It is important to note, that assistance from the RAND in defense planning was one of the many instances of Western support to Ukraine. According to a 2015 study conducted by the Folke Bernadotte Academy of Sweden,

NATO has, as part of the Partnership for Peace (PFF) Programme, supported the training of the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) for several years in order to increase their interoperability with NATO forces. Practical training is primarily delivered through American, Canadian, British and Lithuanian bilateral programmes. These countries have formed a common platform for training of the UAF, the Multinational Joint Commission. Another track within capacity development is medical treatment. For example, Sweden and the United Kingdom focus on training in medical treatment. In addition, NATO military hospitals support wounded Ukrainian soldiers with materials and rehabilitation, including psychological care.[11]

Practically all NATO member countries have contributed to different NATO PfP programs in support of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Besides, they were joined by certain non-NATO countries, like Australia, Sweden, Switzerland and Ireland, who in the last four years actively supported Ukraine as well.[12]

In 2015, given all lessons learned from military actions in Crimea and in Donbas and capitalizing on Western support, Ukraine adopted a clear Security Strategy and a comprehensive Military Doctrine and intensified the transformation of the Armed Forces to the desired level of being capable to deter full-scale aggression from Russia. This provided the general conceptual framework for the transformation in defense.

Further on, taking into account the accumulated experience and responding to calls from soldiers in the field and foreign advisors, Ukrainian authorities finally produced a document, which indicates the generally expected reforms like professional active military, ready to be deployed reserves, NATO standards, relevant budgetary appropriations etc. In February 2016, the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine adopted the Concept of Ukraine’s Security and Defense Sector Development.[13]

In particular, the document further emphasizes the threat posed by Russia and calls for “priority development of intelligence capabilities of Ukraine,” “professionalise the defence forces and establish a required military reserve,” “improve the system of territorial defence to build an active reserve of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, introduce a practical model of cooperation between the units of the territorial defence with the armed formations of the country,” etc.

For the Ukrainian military, this was further specified in the practical plans of structural reforms envisaged in “The State Program for the Development of the Armed Forces of Ukraine until 2020.” [14] The Program outlined five Strategic Goals (Box 3) and provided tentative financial indicators of the cost of their implementation. In the same way as its similar pro-NATO predecessor program of 2005, it calls again for introduction of NATO standards, professionalization of active component and building appropriate reserve.

In fact, Ukraine did accommodate many recommendations by RAND rather quickly, like creation of Joint Operations Headquarters … Fixing in the law the civilian and political status of the minister of defense took a bit longer, but in

Box 3. Strategic Goals of “The State Program for the Development of the Armed Forces of Ukraine until 2020”

|

2018, it finally happened in the Law of Ukraine “On National Security of Ukraine.” [15] However, developing of conceptual documents and plans for reform, increasing the numbers of troops, procurement of armaments and intensifying combat training appeared to be easier to implement, than changing the cultures in defense planning or human resource management (including the gender issue). So far, the progress in the personnel management related issues looks somewhat less impressive than in structural and technical transformations in defense institutions of Ukraine.

In 2018, the Ministry of Defense presentation “White Book 2017. Armed Forces of Ukraine” for the first time devoted a special section to the service of women.[16] It also reported about the modest progress in the implementation of “The Concept of Military Personnel Policy until 2020” developed in cooperation with CIDS – the Norwegian Centre for Integrity in the Defence Sector. Meanwhile, despite reported progress, very much remains to be done in order to change the still alive post-Soviet personnel management cultures in the Armed Forces to the best democratic standards.

In this regard, slow but steady improvements in human security, gender, democratic governance and other dimensions of Defense Institution Building in Ukraine should be contributed in no small part to targeted support of international organizations like NATO, the EU and the OSCE, as well as to continuous efforts by the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF). Since its creation in 2000, DCAF created a comprehensive platform of relevant studies and publications, which were handy not only in building Ukraine’s defense institutions, but in the reform of the other security sector institutions as well.[17]

Conclusion

Overall in the pre-war period of 1991-2013, self-illusion created by the Budapest Memorandum, limitations by ineffective economy, the inconsistencies in national strategy (nonalignment-NATO-nonalignment) and consequent neglect of national defense requirements led to unclear military strategies and a declarative rather than substantial Defense Institution Building process.

On the positive side, during this peacetime building period Ukraine was trying to compensate the impact of its economic weakness on defense through active cooperation with NATO, with partner countries like Sweden and Switzerland, and participation in peacekeeping operations under the auspices of the UN, NATO and the EU. However, in the spring of 2014, the response of the Armed Forces of Ukraine exposed serious weaknesses in all aspects except for the people’s will to defend the country.

By the middle of 2018, over the last four years of war, Ukraine has mobilized, equipped, and trained a substantial force, which looked much more able to fight and resist invading Russian forces and to inflict a high damage to them, if they choose to launch another round of invasion.

It looks like in general terms consensus already emerged in Ukraine on building effective volunteer military with agile active component supported by deployable ready reserve jointly capable to deter possible aggression from Russia. As prior experience proves, the ultimate results of these efforts will depend not only on Ukrainians, but on the cooperation with their partners as well. Ukraine would do its best to adopt NATOstandards and welcome support from NATO countries, but for the time being should rely primarily on its own human, military and industrial potentials.

About the Author

Leonid Polyakov is Chairman of the Board of Experts of the Center for Army, Conversion and Disarmament Studies (CACDS) – a think tank in Kyiv, Ukraine. He was Ukrainian Deputy Defense Minister in March to May 2014, and advisor to the Ukraine Parliamentary Committee on Security and Defense. Previously he has served as First Deputy Defense Minister, 2005-2008, and Director of the military (security/defense) programs at the Razumkov Center, 2000-2005. Mr. Polyakov’s academic record includes Harvard University Fellowship; US Army War College; Frunze Military Academy and Kyiv Command Military School. A retired Ukrainian Army Colonel, his service includes postings on the Ukrainian General Staff and National Security and Defense Council, and command postings in the Soviet Army, including combat duty in Afghanistan. He has published over 100 articles and monographs on issues related to national security governance and defense institution building. E-mail: leonpol2006@gmail.com.

[1] In the general terms, Ukraine inherited almost 800 000 strong conventional military. Armaments included 6 500 tanks, 7 000 armored vehicles, 1 500 combat aircraft, and more than 350 ships. In storages and depots Ukraine had 2.5 million tons of conventional ammunition and more than 7 million pieces of small arms. The nuclear arsenal included almost 2 500 nuclear warheads and a large number of different carriers, including 176 Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles and 44 strategic bombers. See, for instance: Alyson J. K. Bailes, Oleksiy Melnyk, and Ian Anthony, “Relics of Cold War. Europe’s Challenge, Ukraine’s Experience,” SIPRI Policy Paper, 2003, https://www.bicc.de/publications/publicationpage/publication/relics-of-cold-war-europes-challenge-ukraines-experience-sipri-poli....

[2] “Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine,” Ukraine’s Legislation, 2005, http://zakon5.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/3529-12.

[3] UN General Assembly, “Letter dated 7 December 1994 from the Permanent Representatives of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General,” UN Security Council Document S/1994/1399, 1994, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_1994_1399.pdf.

[4] For more details on the US-Ukraine defense cooperation in the 1990s see Leonid I. Polyakov, U.S.-Ukraine Military Relations and the Value of Interoperability (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2004), www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/2004/ssi_polyakov.pdf.

[5] “Participation of the Armed Forces of Ukraine in International Peace and Security Operations,” Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, 2017, http://www.mil.gov.ua/diyalnist/mirotvorchist/.

[6] “On the State Program for Transition of the Armed Forces of Ukraine to Manning with Contract Military Servicemen,” Decree by the President of Ukraine No. 348/2002, http://zakon5.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/348/2002.

[7] Igor Sutyagin and Michael Clarke, “Ukraine Military Dispositions. The Military Ticks Up while the Clock Ticks Down,” RUSI Briefing Paper, Royal United Services Institute, 2014.

[8] Six “waves” of reservists were mobilized since March 2014, and demobilized by the end of 2016 – total of 210 000 reservists.

[9] “By the middle of August 2014 Ukraine lost in ATO 11 aircraft and 9 helicopters,” General Staff, 2015, https://ua.112.ua/ato/do-seredyny-serpnia-2014-r-ukraina-vtratyla-v-ato-11-litakiv-i-9-vertolotiv-henshtab-251835-print.html.

[10] Polly Mosendz, “Ukraine’s Military Budget Will Be over $3 Billion in 2015,” Newsweek, December 12, 2014, http://europe.newsweek.com/ukraines-military-budget-will-be-over-3-billion-2015-291434.

[11] Måns Hanssen, International Support to Security Sector Reform in Ukraine. A Mapping of SSR Projects (Sandö – Stockholm: Folke Bernadotte Academy, 2016), https://fba.se/en/how-we-work/research-policy-analysis-and-development/publications/international-support-to-security-sector-ref....

[12] Hanssen, International Support to Security Sector Reform in Ukraine.

[13] “Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 92/2016,” 2016, www.president.gov.ua/documents/922016-19832.

[14] “The State Program for the Development of the Armed Forces of Ukraine until 2020,” Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, 2017, www.mil.gov.ua/content/oboron_plans/2017-07-31_National-program-2020_en.pdf.

[15] “On National Security of Ukraine,” Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, The Law of Ukraine, 2018, http://zakon2.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2469-19.

[16] White Book 2017. The Armed Forces of Ukraine (Kyiv: Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, 2018), www.mil.gov.ua/content/files/whitebook/WB-2017_eng_Final_WEB.pdf.

[17] “Ukraine. Democratic Security Sector Governance,” DCAF, 2017, https://ukrainesecuritysector.com.