Distorting Your Perception of Russia’s Aggression: How Can We Combat Information Warfare?

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 21, Issue 3, p.77-101 (2022)Keywords:

China, digital citizenship, disinformation, Information warfare, propaganda, Russia-Ukraine warAbstract:

Despite the brutality of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, support or sympathy toward Russia is shown by some actors on the international stage. This could be attributed to the multi-facet information warfare conducted by Russia and its strategic partner China. However, the analysis of information warfare during the current war remains scattered. This article, therefore, adopts a documentary analysis of relevant documents and media sources to conceptualize the forms of information warfare used by these two countries to contribute to future studies. It then proceeds to discuss that the Russia-Ukraine war implies a growing use of information warfare in present and future wars under digitalization. Facing a growing threat posed to people’s cognitive understanding, the democratic community has to be aware of this increasingly dangerous military strategy and develop corresponding solutions. This article suggests that different societal stakeholders must collaborate to develop comprehensive education and thus strengthen digital citizenship. This is vital to nurturing people into critical and responsible citizens, thus equipping themselves with the resilience needed to combat information warfare.

Introduction

Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine clearly violates Ukraine’s territorial integrity and international law. The West has shown unity in countering Russia by imposing unprecedentedly harsh sanctions. In addition to policy action taken by national governments, local citizens in Western countries have also demonstrated their discontent with Russia’s aggression by launching a series of large-scale protests.[1] However, the widespread outrage against Russia is far from universal. Numerous countries and individuals have voiced their support or sympathy for Russia and aired their grievances with Western leadership in international conferences, press conferences, or media platforms.

Such pro-Russian or anti-Western attitudes could be explained by the extensive circulation of manipulated information by Russia and its long-standing strategic partner China. Nonetheless, the analysis of information warfare used by these two countries during the war remains scattered. This article contributes to the security discussion by examining information warfare during the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. The article argues that the war demonstrates how information warfare can help the aggressors mobilize support, suggesting that with increasing digitalization, information warfare will become a more utilized tool. It thus becomes more urgent and important for the democratic community to promote digital citizenship to combat manipulated content.

Since the full-scale Russia-Ukraine war started recently, there is a lack of peer-reviewed scholarly literature directly discussing the war and the use of information warfare. Therefore, this article presents its findings mainly through content and documentary analysis of official and media publications in Russian, English, and Chinese. The author used the relevant keywords for searching and came up with the analysis by identifying the most relevant materials.

This article first conceptualizes the term information warfare. Next, it provides a comprehensive overview of Russia and China’s use of information warfare during the Russia-Ukraine war. Then it discusses the implication of using information warfare in the Russia-Ukraine war on future international rivalries. Finally, the article highlights the importance of digital citizenship to provide solutions for individuals and governments to prevent the distortion of people’s cognitive understanding. It concludes that the Russia-Ukraine war serves to warn us to invest in developing resilience against increasingly invasive information warfare.

Information Warfare

The term information warfare, or information war, was developed by Russia and is widely used. Since the early 1990s, Igor Panarin has been leading the discussion of information warfare.[2] He considers information warfare a psychological confrontation aiming to influence the rivals’ informational environment and protect a party’s environment and thus achieve certain goals.[3] Other scholars, such as Vladimir Lisichkin and Leonid Shelepin, also contribute similar ideas. They suggest that information warfare aims at influencing people’s souls to pressure the domestic audience to act according to the state’s interest and split their rival’s citizens to eliminate resistance.[4]

In the Russian context, information warfare is an offensive tool adopted by the West to disseminate pro-West information to undermine Russia’s influence or destabilize Russia.[5] Russia also acknowledges information warfare’s strengths in promoting its own narratives. Thus, it actively develops information warfare to gain the capability of influencing public opinions and counteracting Western influence. For example, the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, declared that

Our diplomats understand, of course, how important the battle to influence public opinion and shape the public mood is these days. We have given these issues much attention over recent years. However, today, as we face a growing barrage of information attacks unleashed against Russia by some of our so-called partners, we need to make even greater efforts in this direction.

We are living in an information age, and the old saying that whoever controls information controls the world unquestionably sums up today’s reality...

… We must put up strong resistance to the Western media’s information monopoly, including by using all available methods to support Russian media outlets operating abroad. Of course, we must also act to counter lies about Russia and not allow falsifications of history.[6]

Interestingly, Chinese scholars share with Russian scholars similar thoughts on information warfare. The ancient Chinese scholar Sun Tzu famously discussed how information confrontation helps win the battle against other countries.[7] Contemporary scholars also echo Sun Tzu’s ideas. For instance, the father of Chinese information warfare, Shen Weiguang, considers information war a measure to influence one’s cognitive and trust systems to control the enemy and preserve the country.[8]

Realizing how information affects survival, the Chinese government has devoted more attention to information warfare. In 2003, the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee and the Central Military Commission set forth the Three Warfares (三战), including psychological warfare (心理战), public opinion warfare (舆论战), and legal warfare (法律战).[9] The People’s Liberation Army’s recent texts, such as the 2013 Science of Military Strategy and 2014 Introduction to Public Opinion Warfare, Psychological Warfare, and Legal Warfare, have continued to incorporate the Three Warfare into China’s military thinking systematically.[10] This reflects China’s increasing emphasis on how people’s cognitive understanding can influence the development of its strategic competition. Accordingly, China emulates Russia by using information campaigns to promote pro-China narratives, such as during the Covid-19 pandemic, to confront the West.[11]

Meanwhile, the West, especially the United States, has considered Russia and China a threat to the Western-dominated world order. Therefore, in the eyes of Western scholars or governments, the term information warfare represents the weaponized spread of pro-Russia and pro-China information to gain the Western audience’s support.[12] Take the United States National Security Strategy as an example. In the section Information Statecraft, it states that “America’s competitors weaponize information to attack the values and institutions that underpin free societies, while shielding themselves from outside information.” [13] The publication also explicitly discusses the use of information operations by China and Russia.[14] This reflects the West’s specific concern about these two states’ abuse of information.

Table 1. Forms of Information Warfare Adopted by Russia and China during the Russia-Ukraine war.

Forms | Examples |

| Stating that the “invasion” is a kind of “operation” instead |

| Not covering war damages, civilian death, and Zelenskyy’s involvement in the war in detail |

| Establishing fake news laws Removing anti-Russian content Great Firewall |

| Blaming NATO and the United States for causing the war or humanitarian disasters Accusing Ukraine of causing huge war destruction |

| Accusing Ukraine of committing war crimes |

| Posting videos of women supporters and surrendering Ukrainian soldiers Calling Ukrainians ‘neo-Nazis’ |

| Producing fake evidence of Ukraine soldiers’ violent treatment of civilians Exaggerating the surrender number |

| Development of bioweapons in Ukraine |

| Frequent appearance of Russian state media in top results |

| Debunking a 2017 strike video that is not circulated |

While the concept of information warfare appears to be mainly used to politicize either side’s efforts in spreading information favorable to their camp, their conceptualization actually resonates with each other. The spread of manipulated information aims to distort one’s mind to gather support or weaken other countries. We can therefore define information warfare as a combination of measures to manipulate a target audience’s thoughts to achieve certain political goals.[15] Thus, as Golovchenko, Hartman, and Adler-Nissen argue, “information is used as a weapon and the minds of citizens are the ‘battlefield’.” [16]

The Use of Information Warfare for Supporting Russia during the Russia-Ukraine War

In this section, I analyze the use of information warfare to support Russia’s aggression during the Russia-Ukraine war (summarized in Table 1). There was already extensive use during Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.[17] In 2022, however, the utilization of information warfare is even greater during the full-scale war. China’s contributions also amplify the effect of Russia’s information warfare in maintaining domestic support and distorting the international audience’s perception of the war.

Being Cautious about the Wording

Firstly, Russia and China have been handling the wording in their expressions extremely carefully to avoid triggering unfavorable responses. A significant amount of psychological research has demonstrated the wording effect, which suggests that a slight change in the wording can significantly affect one’s preference or perception of an issue.[18] Both Russia and China have made use of this effect to convince the international audience that Russia’s military activities are not wars. They have consistently refused to frame Russia’s aggressive acts as wars or invasions, which are negatively loaded terms.[19] Instead, Russia’s offensive activities are called operations, such as “a demilitarization operation targeting military infrastructure” or “a special military operation to defend the people’s republics.” [20] Such sanitization of language could sway public opinion on Moscow’s aggression, thus reducing domestic and international resistance to Russia’s expansion.

Biased Coverage of Information

Russian and Chinese media have been selectively reporting on the war, so their audiences see the Ukraine crisis through a different lens. Since people collect information on political issues through media sources, selective reporting could shape the audience’s perception of the conflict, thus weaponizing information to serve the regime’s interests. Russian media understates the scale of Russia’s military activities and war destructions.[21] For example, Russian state TV avoids reporting the situation in Kyiv and Kharkiv, where people’s houses suffer devastating bombings.[22] Chinese state media also scarcely cover civilian death caused by Russian troops in detail.[23] With such media bias, the information about Russian troops’ brutality becomes obscure. The biased portrayal of the war development could influence people to believe that Russia is not a violent aggressor. The audience is therefore tricked into believing in a manipulated story that the two governments want their citizens to consider. As a New York Times article suggests, Russia has been manipulating the messages Russians receive so they do not believe Russia wages war in Ukraine.[24]

Censorship

The two countries have increased levels of censorship of their media to further control the narrative around major events. As autocratic countries, China and Russia have always tightly controlled the spread of information. Such information control has been strengthened significantly during Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine. Notably, building on previous laws like the Russian 2019 Fake News Law and the 2019 Russian Disrespect to Authorities Law, Russia promulgated the Russian 2022 Laws Establishing War Censorship and Prohibiting Anti-War Statements and Calls for Sanctions on March 4, 2022. According to the laws, disseminating “false information” about the exercise by Russia’s state bodies could result in fines amounting to five million rubles and imprisonment of up to 15 years.[25] Such harsh penalties could suppress the genuine voices of people or the media. Given the shrinking freedom of speech and the soaring risk of operation in Russia, some Western media companies (e.g., ABC News, CNN International) and Russian independent media (e.g., Radio Echo, Znak.com, Dozhd) have suspended their operations in Russia.[26],[27] Moreover, apart from combating anti-government information produced in Russia, the Moscow government also limited Russian citizens’ access to foreign media (e.g., BBC and Deutsche Welle) to contain the spread of anti-war materials.[28] As a result, anti-Russia information is hardly circulated in Russia.

Meanwhile, China also launches some milder yet robust censorship measures. State-owned news agencies (e.g., Horizon News) would filter anti-Russia or pro-West content.[29] Chinese media also refuses to translate or broadcast content with anti-Russia messages. One example of the former is the absence of translation for President of the International Paralympic Committee Andrew Parson’s condemnation of Russia at the opening of the 2022 Winter Paralympic Games.[30] An example of the latter occurred with the lack of broadcasting for the English Premier League Matches in which players planned to express their support for Ukraine.[31] It is worth noting that China’s Great Firewall continues to act in this critical crisis, which is often neglected in related discussions. China uses the Great Firewall to complement its new censorship measures. People are blocked from accessing foreign websites (e.g., Wikipedia), social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook), and search engines (e.g., Google).[32] Thus, Chinese citizens can hardly access foreign anti-war information. All these measures result in the circulation of one-sided information within China that encourages the domestic community’s tendency to support Russia’s invasion.

Distortion of Responsibilities

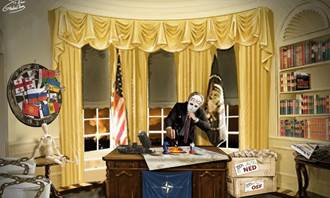

Despite being the initiator of the war, Russia has consistently shifted the responsibility to Ukraine and the West with China’s assistance. Putin has insisted that the “special military operation” is a forced measure.[33] The Moscow Government and Chinese state media leveraged the “Blame NATO” argument, developed by political scientists like John Mearsheimer,[34] to blame NATO and the United States for failing to satisfy Russia’s demand for security and thus forcing Russia to attack Ukraine.[35] China’s Foreign Ministry even accused the United States of being “the real trouble-maker and threat to security in the world,” [36] which is supported by fierce criticisms against the United States by media agencies like China Military Online and People’s Daily.[37] China’s state-led media Global Times even created the hashtag #UkraineCrisisInstigator to blame the United States and NATO.[38] It also published a series of stories and cartoons (e.g., Figure 1) to show how the United States is bringing trouble to the world [39] and distract the audience from the Russia-Ukraine war by discussing how the United States created humanitarian disasters and bloody turbulence in previous wars like Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan.[40] These could redirect the audience to ignore Russia’s responsibility for causing the war while undermining the West’s credibility and thus discouraging participation in the West’s anti-Russian call.

Figure 1: A Cartoon Published in the Global Times Blaming the United States for Causing the War. (Source: Global Times, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202203/1256665.shtml)

Meanwhile, apart from criticizing the United States and NATO, Russian TV also accused Ukraine of being responsible for the strikes in the Donbas region of Ukraine to shift the responsibility for the severe damages to infrastructure, housing, and other facilities.[41] This could deter citizens in other states from developing sympathy towards Ukraine, thus favoring Russia’s expansion.

Baseless Accusations

Russia has accused Ukraine of harming civilians or threatening Russia without justification. Russia asserts that Ukraine is committing genocide against Russian-speaking people in the eastern territory of Ukraine.[42] Moreover, Russia’s state-controlled Channel One has spread claims that Ukrainian troops were bombing residential buildings and warehouses with ammonia, despite lacking evidence.[43] It also alleges that Ukraine is using more than 4.5 million civilians as human shields, thus committing war crimes.[44] For instance, the chief spokesman for the Russian Ministry of Defence, Igor Konashenkov, stated that “[T]he Kyiv regime uses the residents of the city as a ‘human shield’ for the nationalists who have deployed artillery units and military equipment in residential areas of the capital.” [45] This, again, is intended to help Russia shift the responsibility for causing the war to its enemy and reduce resistance to its invasion.

Use of Emotionally Charged Content

Russia and China have produced emotionally charged content to derogate Ukraine and the West or defend Russia’s reputation. Emotionally charged materials can prompt the audience to accept and spread ideas without carefully considering or examining evidence.[46] On the one hand, Russia and China have circulated pro-Russia military activities materials (e.g., clips of women supporting Russian soldiers [47] and clips of surrendered Ukraine soldiers [48]) to boost Russians’ morale and consolidate the consensus on Russia’s military activities. In addition, the sense of competence promoted by the materials could help Russia arouse national sentiment and avoid domestic resistance. On the other hand, Russia has been producing emotionally appealing content to change the perception of Ukraine, where people may believe their government is full of Nazis. Towards that aim, officials and media refer to Ukraine as a neo-Nazi force and compare Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the Soviet Union’s defense of its homeland from Nazi aggression.[49] Such content can vilify the current administration and stir fear among Russian citizens or racial groups that Nazi Germany has threatened, thus persuading these people to support Russia’s “de-Nazification” military activities as a liberation.

Fabricated Information

Russia has fabricated information about the war to shatter Ukraine’s image and morale. While some aforementioned accusations lack evidence, Russia has attempted to produce evidence to justify its claims. For example, Russia planned to produce a video in which Ukrainian soldiers treat civilians violently to jeopardize Ukraine’s reputation on the international stage.[50] This has altered the truth and deceived individuals, consolidating and expanding Russia’s support base. Additionally, Russia has fabricated materials targeting Russian and Ukrainian audiences to distort the war development. Russia’s state-owned news agency RIA News has denied that Russian aircraft, helicopters, and armored vehicles were lost,[51] which contradicts international reports.[52] Russia also spread false claims that Ukraine’s military personnel were leaving their positions, contradicting the Ukrainian officials’ firm refusal to surrender or escape.[53] Moreover, Russia has been exaggerating the number of surrendered Ukrainian soldiers.[54] These efforts could undermine Ukraine’s and boost its own troops’ morale, thus increasing the likelihood of winning the war. By creating an image that Russia has the upper hand in the war and the Ukrainian militaries are cowardly, the fabricated materials could weaken Ukrainian support for its government and encourage Russians to support Moscow’s “special military operation.”

Conspiracy Theory

Russia and China have been spreading conspiracy theories to encourage the audience to support Russia’s invasion. Conspiracy theories refer to unverified allegations that some hidden or powerful agents carry out secret plots to cause some political or social events to happen.[55] Psychological studies have suggested that when people lack trust in others or feel insecure, they tend to believe in conspiracy theories.[56] Distrust towards the West has risen in countries like China, Iran, and Turkey.[57] This has provided favorable conditions for the spread of conspiracy theories. Russian government and media have been spreading messages that Ukraine has built up bioweapon-manufacturing laboratories with the United States’ financial assistance.[58] Such claims are further disseminated by Chinese media virally.[59] The head of the Russian space agency Roscosmos also wrote that Ukraine had developed a bioweapon that could hinder the reproductive capability or immunity of Russians, thus making them vulnerable to extinction.[60] This could further stir controversies and breed hostility of their domestic audience and non-Western audiences against the West.

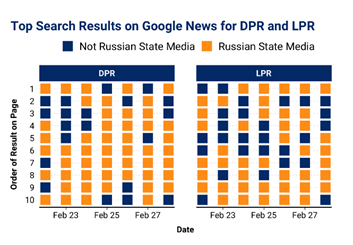

Potential Search Engine Optimization

Russia may have practiced search engine optimization (SEO) to accelerate the spread of the pro-Russia narrative. SEO is the practice of improving the search ranking of the materials, such as by mentioning specific trending keywords.[61] For some search items (e.g., DPR and LPR), Russian state media appear more frequently in the top search results.[62] While it remains unclear whether it is caused by Russia’s deliberate manipulation of its content to fit the algorithms or coincidentally caused by the mass production of content, this issue warns us that SEO could significantly affect the results of people’s search for information. Seeing only the Russian sources may distort their views and perspectives in line with state-sponsored fabrication.

Figure 2: The Top Search Results on Google News for Two Key Items Related to the War (Source: Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/the-surprising-performance-of-kremlin-propaganda-on-google-news/).

Disguising Disinformation as Fact-checking

Lastly, Russia has introduced a new tactic that has never been seen in other conflicts: disguising disinformation as fact-checking. Traditionally, fact-checking has been regarded as an effective way to combat fake information. Nonetheless, Russia has used the rubric of “fact-checking” to circulate more fake claims by using fake stories to refute another fake story. For example, pro-Russian forces claimed that Ukrainians were circulating a video of a strike to accuse Russia of bombing Kharkiv. Another “fact-checking” video is then posted to explain that the strike video was actually a video shot in 2017 and the Ukrainians were spreading lies. Nonetheless, there is no evidence proving that the Ukrainian government circulated the strike video.[63] After examining the metadata of the videos, Darren Linvill argues that such debunking videos are created by the person who made the fake strike video.[64] Meanwhile, other “fake” and corresponding “fact-checking” videos were also presented by state-controlled channels.[65] This new tactic has made information more confusing while tricking some audiences into believing that Russia spreads correct information and Ukraine is the liar, thus helping the Moscow government gain support.

Summary

In essence, Russia has been actively involved in information warfare during the Russia-Ukraine War, while China has also played a supporting role in assisting its partner’s invasion. The variance, extensiveness, and scale of Russia’s battlespace use of people’s cognitive abilities and understanding have been unprecedentedly large. Old tactics have been refined, and new tactics have also been developed (Table 1), thus enhancing the effectiveness of manipulating information as strategic tools in building domestic and international support.

The Implication of Information Warfare

With rich resources, the state authority is capable of producing, manipulating, and circulating content to promote certain positions and views.[66] Meanwhile, due to the abundance of information, people often experience information overload, which refers to being overwhelmed by an excessive amount of information.[67] They lack the capacity and time to process all information, so they need to seek shortcuts to consume information.[68] Manipulated information is an attractive shortcut because it is brainwashing, invasive, or emotionally appealing.[69] However, such information is deliberately distorted, and the audience may not notice that. Therefore, information warfare can prompt people to believe and behave in a way aligned with the initiator’s political goals.[70] The weaponization of information and people’s cognitive understanding could, therefore, significantly affect the supporting base for the aggressor. The strong domestic support for Russia’s invasion and the surprising sympathy towards Russia should thus be attributed to the factor that Russia and China have been disseminating manipulated information. Such information warfare has helped counteract pro-Ukraine information influence, thus helping Russia to reduce resistance.

Domestically speaking, according to a poll conducted in Russia by the Levada Center, 77 % of respondents support Russian military actions in Ukraine in May 2022 (Table 2).[71] Regarding China, a significant number of posts were cheering for Russia’s “anti-Western” war.[72] It is true that in autocratic countries like Russia and China, the credibility of media and polling is questionable because there is censorship or falsification of the preferences.[73] People are often unwilling to criticize the government.[74] Therefore, the support for Russian military actions is likely overstated. Nonetheless, the poll has been conducted by the only remaining independent pollster in Russia, which is a more trustworthy or legitimate source.[75] Some pro-Russian and anti-Western posts are also created or shared by China’s domestic audience rather than by the state media, which implies a certain level of national support for Russia. One could not ignore the large domestic supporting base of Russia’s invasion and the widespread distortion of public opinion. Information warfare clearly plays a role in gathering domestic support for Russian aggression.

Table 2. Domestic Support for Russian Military Actions in Ukraine.

Category | March 22 | April 22 | May 22 |

Definitely support | 53 % | 45 % | 47 % |

Rather support | 28 % | 29 % | 30 % |

Do not support | 14 % | 19 % | 17 % |

Difficult to answer | 6 % | 7 % | 6 % |

Source: Levada, “Conflict with Ukraine,” June 2022.

Internationally speaking, while the Western powers are furious at Russia’s unlawful invasions, a number of countries unexpectedly refuse to join the Anti-Russian call. Thirty-five countries like India and South Africa have abstained in the UN vote on the resolution condemning Russia’s invasion.[76] Some citizens of African countries even considered Putin their hero who is brave in confronting Western hegemony.[77] Admittedly, other factors (e.g., discontent with the West’s past military activities, hypocritical embracement of Ukraine, biased treatment of non-Western countries) could affect various countries’ attitudes towards the West’s anti-Russian call.[78] However, information warfare can complement other factors to further intensify people’s distrust or hostility toward the West, thus prompting them to stay away from the West or even align with Russia. Therefore, apart from reducing the legitimacy of the anti-Russian initiative and showing a weakness of the West in leading the anti-Russian chorus, the non-negligible support or sympathy towards Russia also implies that the spread of state-sponsored biased information can strongly influence people’s attitude towards a political issue.

Meanwhile, we also need to acknowledge the important implication of information warfare on future wars. Thanks to the development of satellites, the internet, and other digital technologies, the spread of information, including propaganda and disinformation, will become faster and less costly. As a result, both domestic and international audiences will have greater exposure to such manipulated information.[79] Therefore, information warfare will become increasingly effective, as demonstrated by the Russia-Ukraine War.

Admittedly, social media platforms are now collaborating with independent fact-checkers to label false and misleading content, which could make the dissemination of manipulated information difficult. Nonetheless, the current algorithms and human moderation are far less than perfect. If there is an influx of diverse manipulated information, it is costly to remove all the content, not to mention whether this could constitute a violation of freedom of speech.[80] The threat of information warfare will therefore remain despite the development of fact-checking mechanisms.

The use of information warfare will persist and people’s cognitive understanding is at risk of foreign intervention or distortion. The term fact-checking may end up being a tool for politicians to debunk false information to make other false information more persuasive, so people will find difficulties in finding reliable sources of information. Truth, therefore, becomes even more difficult to be identified. More people will be tricked into believing manipulated information, which means their perceptions can be shaped by malicious material to become an aggressor’s supporter. Wars no longer solely take place on a physical battlefield with guns and missiles, but people’s minds will become a more important arena.

What Should We Do? More Education Is Needed

While the rise of information warfare is an uncomfortable truth to truth-seekers like us, we must stand against the malicious manipulation of information to defend the independence of our minds. The same applies to the government because citizens’ inability to distinguish truth can seriously threaten security and ruling stability.[81] Thus, more education on analyzing information is needed to help people maintain their rationality.

According to Zara Abrams, cyber citizenship (also commonly referred to as digital citizenship), which refers to the combination of digital literacy, responsible behavior, and awareness of the threat of online manipulation, could effectively help individuals tackle information warfare.[82] This combination provides a holistic framework for individuals to learn to deal with manipulated information and for the government to implement counter-information warfare education.

Individuals

It should be acknowledged that the characteristics of digital citizens largely resemble those of ordinary citizens. Digital citizens have their corresponding rights and responsibilities in the virtual community as citizens in the physical community.[83] Critical thinking, in particular, is an element of a good digital citizen that deserves our attention.

Individuals must recognize that they are targets in information warfare. With the increasing trend of using information warfare, all citizens should be aware of the possibility of coming across manipulated information on media platforms. It is, therefore, of utmost importance for individuals to enhance their digital literacy. While digital literacy has been a contested concept, it can be summarized as the skills, knowledge, and competence of assimilating, evaluating, and reintegrating information properly and meaningfully.[84] It helps individuals exercise critical thinking and enhance their resilience against information warfare.

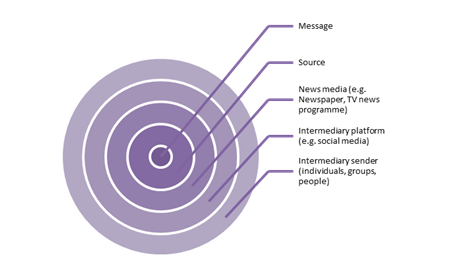

First, individuals have to identify the sources of information. Some media and intermediaries tend to show bias or be weaponized by the state to distort the audience’s mind. Examples include state-owned media, individuals or media affiliated with political parties or certain political stances, and sources from autocratic countries with censorship, such as Global Times and People’s Daily in China, as mentioned. This implies that the sources themselves reflect their stance on certain issues, which impacts their credibility. Individuals should therefore check the sources’ political and ideological affiliations before fully trusting the information. They should also strive to collect accurate and objective information from more independent and trustworthy sources, which undergo a rigorous report process, provide up-to-date references, and offer balanced perspectives. It is also possible that biased media and intermediaries could cite ‘credible’ sources out of context to gain higher credibility, so individuals should check not only the sources but the citations as well.

Second, individuals have to identify emotive and propaganda elements. It is common for information warfare to adopt offensive or emotive language to stimulate readers’ interest and affect their rationality. For example, China has been using negative words like “vampires,” “brutality,” and “hegemony” to describe the United States during the Russia-Ukraine war so as to cultivate an anti-American sentiment.[85] Therefore, people must stay calm when they read emotive content so that they can rationally analyze information and avoid being weaponized by aggressors.

Third, individuals should develop the habit of checking multiple sources. As mentioned, some information channels selectively report facts, convey bias, or spread fake news, so individuals cannot rely on one single source to grasp the full picture of the issue. Besides helping individuals gain a deeper and broader understanding of the issue, going through more sources also allows individuals to check whether some claims are false or really exist. Thus, they can verify whether debunking videos are debunking existing or artificially created false information, and so rendering this new tactic less effective.

By developing digital citizenship and enhancing their digital literacy, individuals can critically analyze information from different layers of sources (Figure 3). Individuals could then identify whether the sender, intermediary platforms, and media are intrinsically biased, thus evaluating the source’s trustworthiness and message. They could also gain the capability of evaluating the credibility of different messages by comparing them with a wide range of sources or with rational analysis. This helps to avoid traps of manipulated information that penetrates these layers. This could significantly reduce information warfare’s effectiveness in exploiting one’s cognitive and decision-making capability.

Figure 3: Five Layers of Information Channels (Source: Karlsen & Aalberg, “Social Media and Trust in News,” adapted by the author).

Moreover, the possibility of coming across manipulated information also means that other netizens can be weaponized by receiving or disseminating manipulated information. Thus, posting, commenting, and spreading content can have political implications: Individuals’ acts in the virtual community can unknowingly assist the aggressor in circulating manipulated information, thus facilitating its aggression.[86] Therefore, individuals should be responsible for their actions in the virtual community. They should think before posting and sharing content. Everyone’s wholehearted contributions are vital to preventing the circulation of manipulated information.

The Government

Individuals may not recognize the danger posed by information warfare as manipulated information unconsciously affects one’s mind. Therefore, the government needs to take an active role in promoting digital citizenship education so its citizens can be resilient against information warfare. This could, in turn, encourage citizens to take up individual efforts such as those discussed above to improve their digital literacy and critical thinking skills. The government can intervene in two main ways to avoid public defeat in information warfare.

The government has to develop a comprehensive curriculum for educating people on the importance and skills of tackling information warfare. While some countries have developed education for training students’ analytical and evaluation skills, some (e.g., the United Kingdom) failed to refine the curriculum to adapt to the rapid changes in the digital environment.[87] Also, some digital citizenship projects (e.g., the Digital Drivers’ License project in the United States) are limited to certain age groups, thus ignoring other students and/or adults who are equally or more vulnerable to manipulated content.[88] Given the growing use of information warfare, the inadequacies of current curricula are becoming more obvious. Policymakers should therefore devote more resources to promoting digital citizenship. The curriculum has to include more content to help students identify fake news, disinformation, biased information, and other common elements of information warfare, as well as encourage criticality. Formative and summative assessments (e.g., tests, conversations) are also necessary to help students fully understand their knowledge and skills and assess teaching effectiveness.[89]

Meanwhile, teachers and schools may lack the relevant knowledge or resources to implement such curricula and assessments. As a principal stakeholder in the learning ecosystem, the government has to organize training, provide guidelines, or produce learning resources (e.g., handouts, worksheets, teaching plans, and presentations) to facilitate teaching and learning.[90] These are essential for the school to teach digital citizenship and literacy effectively.[91] If possible, the government can leverage the power of other stakeholders like think tanks and non-governmental organizations to fill in the resource gap and develop supporting measures. The institutionalization of such education could help nurture our future generations into responsible and digitally literate citizens who can confidently survive in the turbulent digital era.

Furthermore, the government has to launch media promotions to complement school education. While school education promotes digital citizenship immersively, the non-student public could not receive such valuable lessons. Mass media and social media promotion with high public coverage are thus needed to raise public awareness of information warfare effectively. These promotions can help improve people’s understanding of social issues, mobilize support, and remind them to protect themselves against certain threats.[92] In this case, advertisements and promotional videos can be produced to provide timely and rich information about information warfare. This helps the public understand the risk posed by information warfare, thus encouraging public engagement in developing digital citizenship. With the use of multiple channels, the government can effectively help its citizens think, analyze, and evaluate critically, thus strengthening their immunity to manipulated content.

It must be emphasized that such education projects should be long-term with constant evaluations and adjustments because of the fast-changing nature of media.[93] As Gianfranco Polizzi and Ros Taylor point out, “Misinformation is not new. But in the digital age, misinformation has acquired new forms and new means to spread rapidly.” [94] The Russia-Ukraine War has already reflected that new information warfare strategies are being developed. In the future, with the growing attention on this new warfare, more creative and effective strategies will be persistently introduced. The government must review its education projects frequently to adapt to the new context. Quantitative and qualitative research can be conducted regularly to evaluate whether students are digitally literate and whether more supporting resources are needed. It also needs to reference other countries’ examples to improve its education. In this way, the whole country can become more capable of defending itself from malicious manipulation of information.

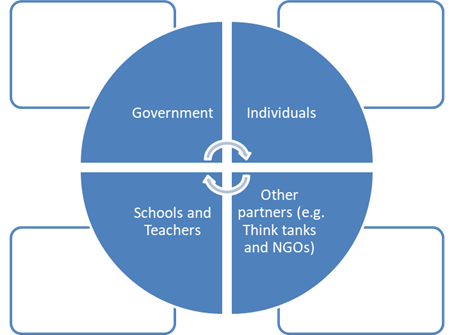

Summary

The success of strategies for combating information warfare depends on the contributions from multiple parties, as synthesized in Figure 4. The importance for individuals to enhance their digital citizenship provides insights into the government’s future policy direction. The government has to coordinate and collaborate with different sectors closely to gain support or advice to improve its current education in and out of school. This helps the country overcome the challenges posed by information warfare.

|

Conclusion

The Russia-Ukraine war has demonstrated that the extensive use of information warfare can profoundly impact people’s attitudes to the war and its development. By providing a systematic categorization and analysis of the use of information warfare during the war, this article contributes to future security studies investigating old and new tactics while focusing on a theoretical perspective. More empirical research is needed to comprehensively evaluate the impact of such tactics, thus assessing the threat posed by information warfare.

It should, however, be noted that this article is not entirely attributing some people’s support towards Russia in the war to information warfare. Other factors, such as Russia’s well-established positions in developing countries and the backlash of the West’s harsh sanctions, could also cause individuals to be more pro-Russian in this crisis. These factors, including information warfare, could complement each other to reinforce people’s pro-Russian attitudes further. This article, therefore, aimed to highlight, but not over-emphasize, the role of information warfare in the war.

Meanwhile, this article has shed light on the multi-faceted use of Information warfare in the Russia-Ukraine war. Information warfare is rapidly evolving, but unfortunately, the democratic community is not yet well-prepared for the increasing coverage of manipulated information. There is much for us to do to develop an effective response to the challenge posed by manipulated content. Therefore, such dynamics of international security are serving as an alarm that the democratic community and security discipline must keep an eye on the development of such creative forms of warfare so that we can respond appropriately to future information warfare.

The future of democracy could remain hopeful if individuals and the government recognize their important stakes in shaping a community that is resilient against information warfare. Individuals have to step up to be critical and responsible citizens. Comprehensive education developed and promoted by the concerted efforts of multiple parties is also necessary to make citizens capable of combating manipulated information. Therefore, close collaboration between the government and relevant parties is strongly encouraged.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

About the Author

Ho Ting (Bosco) Hung is a BSc in Politics and International Relations student at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). He is a member of the International Team for the Study of Security Verona. Recently, he presented at the Oxford Hong Kong Forum 2022 and was interviewed by Asharq News and Al Jazeera to provide a geopolitical analysis of world politics. He has written for The Webster Review of International History, Oxford Political Review, International Policy Digest, Modern Diplomacy, The Geopolitics, and International Affairs Forum. He is mainly interested in Sino-US relations, Chinese politics, foreign policy analysis, gender, political economy, and human rights.

E-mail: h.t.hung@lse.ac.uk

press.com/2022/05/20/russian-propaganda-adapts-to-the-war/; Sheng Jun, “Fanning up Flames of Trouble, US Is to Blame for Tension in Ukraine,” China Military Online, March 17, 2022, http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2022-03/17/content_101414

90.htm; Vibhuti Sanchala. “China Urges US to Take Responsibility for Ukraine War; Slams Sanctions on Russia,” Republic World, April 11, 2022, https://www.republicworld.com/world-news/russia-ukraine-crisis/china-urges-us-to-take-responsibility-for-ukraine-war-slams-sanctions-on-russia-articleshow.html.

1584059/russia-news-ukraine-war-us-bioweapons-targeting-reproduction-rogozin-vladimir-putin.

2022/06/02/konflikt-s-ukrainoj-2/. – in Russian.