Hofstede’s Power Distance Matrix: Law Enforcement Leadership Theory and Communication

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 21, Issue 1, p.61-72 (2022)Keywords:

cultural environments, eth¬ics and public service, Hofstede matrix, leadership theory, managementAbstract:

Hofstede created his theory with its dimensions by working with various private companies. In 2021, the author had the opportunity to do all this for an organization that trains civil service employees. The central question of his research was how to integrate Hofstede’s dimensions concerning managerial communication into an environment based on other cultural and ethical foundations. The quantitative analysis employed a questionnaire consisting of closed and open-ended questions. Staff and students of the Faculty of Law Enforcement, University of Public Service, responded to the questionnaire. The responses were processed using statistical tests suitable for confirming or refuting a hypothesis. The new research findings indicate that it is worth considering how the six dimensions set up by Hofstede could improve law enforcement if incorporated into leadership awareness during leadership training.

Theoretical Background of the Research

Within the framework of intercultural communication, the theory of cultural dimensions is linked to the name of Geert Hofstede. With the help of factor analysis, Hofstede was able to compare the cultural effects of society with the value system of the members of society and thus evaluate the obtained results in relation to each other. The research results first ensured the creation of four, and later a fifth and a sixth dimension.

Hofstede founded IBM Europe’s Personnel and Research Division in 1965 and led it until 1971. Between 1967 and 1973, he conducted research on national differences among staff members of large multinational corporations and their subsidiaries around the world. More than a hundred thousand people participated in the surveys. Hofstede assisted them in completing the surveys and analyzed the results. The comparison and attitude surveys initially covered forty, and were later expanded to fifty different countries and three different regions, thus creating one of the largest coherent cross-border databases of its age.[1]

The initial analysis defined four dimensions of national cultures in which cultural values could be systematically classified: power distance (i.e., the strength of social hierarchy), masculinity and femininity (i.e., task versus person orientation), uncertainty avoidance, and individualism-collectivism. These dimensions touched on four different anthropological problem areas that were addressed differently by various national societies, in particular: how to deal with inequality, how to deal with insecurity, the individual’s relationship with themselves or their primary group, and the emotional consequences of task-orientation or more person-orientation in a working environment.[2]

Between 1988 and 1991, Michael Harris Bond and colleagues successfully conducted a renewed experiment among students in twenty-three different countries using a survey tool developed by Chinese employees and executives. As a result of the research, Hofstede’s dimensional theory was supplemented with a fifth dimension, long-term orientation (the relationship of past, present, and future with the harmony of action), called initially Confucian dynamism.[3],[4]

Ten years later, a Bulgarian researcher, Michael Minkov, extended the original dimensions created by Hofstede to 93 other countries, using the so-called “World Values Survey” method. The research protocol refined the original dimensions and also successfully explored the differences between national and individual level data. A new, sixth dimension built around leniency and self-restraint was added to the existing five dimensions.[5]

Hofstede’s theory of dimensions has helped to map intercultural traditions. It is still being used by researchers and consultants in many areas of international business and communication (including management, psychology, and sociology).

In business life, for example, it is agreed that communication within and outside the organization is the key to success and one of the primary conditions for organizational functioning. Professionals can interact with workers from other countries within a company as they form a community. Further, they have to contact representatives of other organizations who may be born into another society. Hofstede’s model helps with all this by providing insight into other cultures. Communication between different cultures requires knowledge of cultural differences because what is perfectly acceptable and natural in one society can be confusing or even offensive in another. Hofstede’s dimensions affect all levels of communication, including both verbal (words and language itself) and non-verbal (body language, gestures, clothing, protocol, guidelines, rules, value systems, ethics) communication, and also cover oral and written communication.

The question, therefore, is how external and internal communication of the employees of public administration bodies of strict bureaucracy relate to all this. The interpretation of the values arising from the organizational culture in the field of law enforcement, as well as the strict centralized legal relationships and the principle of issuing and receiving instructions, which also determine the value system and its dimensions of Hungarian citizens from different cultures, impacts the internal communication of the organization.

Law Enforcement in the Focus of Research

Are the leaders in the strictly centralized police model, which operates based on command and unconditional obedience and exhibits almost all the leadership styles, communicate in a way that improves effectiveness, manifests expected performance, and efficiency in the light of and as a result of the work of employees? [6]

In Europe, where the importance of borders is diminishing, the work of the police is constantly the focus of attention. Above all, the heart of the debate is the effectiveness of the police and how they can tackle crime, including international crime (but it is by no means limited to this issue). In democracies, the power of the police is limited to the extent it is acceptable to fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals. The right balance needs to be struck between these two equally important interests. The means by which that balance can be maintained are also important. In the case of police ethics, this is the issue that is at stake.[7] Is there a personality distortion, is communication motivating, or does it break the consciousness so that the work is realized in a conveyor-like way without question?

Does the autocratic leader tend to dominate the conversation, emphasize his own opinion, and interrupt his partners? Does the democratic leader allow the staff to express their own views and will in the course of communication? Is the laissez-faire leader equal in communicating with the other group members?

Hofstede’s power distance matrix can provide an answer to all of these questions, as we can determine the extent to which members of an organization accept that power is unequally distributed. This is especially true during the issuance of the order and the measures taken against the citizens.

In terms of individualism versus collectivism, the extent to which people are able to integrate into groups can be assessed. Is the individual able to assert himself in a strict bureaucratic system where his self-interest must be pushed into the background against the organization’s goals? Can you work in a team, or will you be more successful on your own?

With the help of the study of avoiding uncertainty, it is also possible to assess whether the codes of ethics characteristic of bureaucratic organizations are indeed guidelines and beliefs among those working in the organization. Can they identify with it or, on the contrary, do they rely on absolute truth?

Regarding masculinity versus femininity, one examines whether enforcement and performance orientation (masculine qualities in Hofstede’s model) or cooperation and care (feminine qualities in Hofstede’s model) dominate in the law enforcement organization.

The examination of long- versus short-term orientation focuses on the relationship between responding to current and future challenges and the reflections of the past. For example, do law enforcement leaders prioritize their organization’s traditions or the accelerated globalization? Is adaptation for pragmatic problem-solving necessary, or is there no need to improve the organization?

In the sixth dimension, leniency and restraint play a role, referring in this respect to the degree of freedom, that is, the restraints imposed on the worker by the bureaucratic organization, the law enforcement. Think, for example, of restricting fundamental rights.

Organization of the Study

The general aim of the study is to create a data source that gives a realistic picture of Hofstede’s grouped dimensional theory in law enforcement in view of the selected sample and enhance the leadership theory of police leaders.

Before elaborating the questions necessary for the survey implementation, basic historical research was carried out through an analysis of primary and secondary sources. The survey method forms the backbone of scientific methodology. It employs quantitative analysis to satisfy the research needs (i.e., obtaining as much information as possible). The method is suitable for achieving the objectives (i.e., allowing to make evidence-based recommendations) and lays down pillars (i.e., divisions are comparable, trends can be described in a qualitative and quantitative context). The survey was conducted online.

The sample consisted exclusively of the students of the Faculty of Law Enforcement. When selecting the sample, the author placed particular emphasis on maintaining the rules of research ethics, addressing, among others, publicity and anonymity issues. During the compilation of the survey, open-ended and closed-ended questions had to be answered. A total of 22 people completed the questionnaire, so the survey cannot be considered representative.

After compiling and completing the questionnaires, the responses were compiled into a database. Among the statistical tests, the author calculated maximum, minimum, mean, and standard deviation functions and performed scaling suitable for estimating correlations.

The author’s hypothesis is that the power distance in the law enforcement organization is rather large, individualism is more prevalent, uncertainty is avoided, long-term orientation is stuck in the past, and the constraint is significant.

Research Results

Age

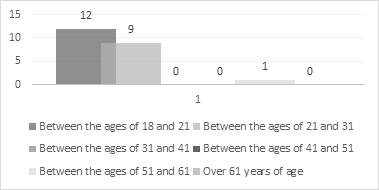

One question asked was about the respondent’s age. From the categories listed, the respondent had to choose which interval within the category included his age. Only one category could be selected from the list. According to the results, 12 people were in the 18-21 age group and 9 in the 21-31 age group. One person indicated the category between the ages of 51 and 61, which thus proved to be an invaluable result, as the professional employment relationship precludes a person from studying full-time at this age (Figure 1). In Hungary, in the 2019/2020 school year, 1 666 thousand children and young people, 86 % of the affected 3-22-year-olds, participated in full-time training in public education and higher education at various levels, of which 203.6 thousand in higher education.[8] Consequently, the age rate of the respondents, which is predominantly the same as the age of those studying full-time, correlates with the maximum value.

Gender Identity

The respondent had to select the category that currently characterized their gender (Regardless of sex, they were classified at birth). Only one category could be selected from the list. Among the respondents were 17 men and five women. Due to the creation of equal opportunities, the transgender category was also set up; however, there was no such gender identity among the respondents. Comparing the data with the survey of the Central Statistical Office, it can be

Figure 1: Age of the Respondents.

stated that due to the gender composition of the relevant age group, the number of men exceeds the number of women of almost all ages, with the exception of the 19-23 age group.[9] In the research, the number of men is much higher than women, so the number of women represented the minimum value.

Specialization

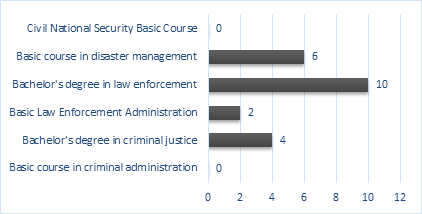

Respondents were asked about the area of their specialization. They had to select one category for the field of their current studies. No one among the respondents took the undergraduate civil national security or the criminal administration course. Two respondents were taking the basic course of law enforcement administration, ten – the basic training course in law enforcement, four – the basic training course in crime, and six – the basic course in disaster management (Figure 2). In 2019/20, 4420 people applied to study in the Faculty of Law Enforcement, of which 1567 persons enlisted in their first choice. As a result of the admission process, only 701 people started their studies.[10] The maximum value in this respect (in 2021) was formed by the graduates of the Bachelor’s degree program in law enforcement.

Figure 2: Field of Specialization of the Respondents.

Professionalism

We wanted to know whether the respondent saw law enforcement as a profession or simply as a job. Twenty respondents consider law enforcement to be a profession, while two interpreted it simply as an opportunity for employment.

Leadership Styles

The question posed concerns leadership styles. The respondent had to choose the category that s/he thought was best suited to lead the police force. Only one category could be selected from the list. According to the respondents, nine people consider the autocratic leadership style and 13 – the democratic leadership style as most suitable for leading the law enforcement organization. No one selected “laissez-faire” as the most suitable leadership style.

Hofstede Power Matrix and Dimensions

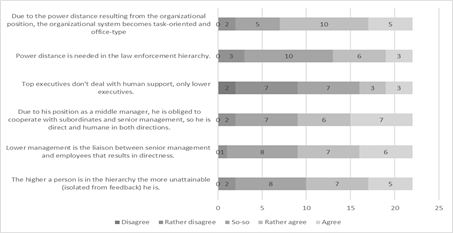

We wanted to elicit the views of the respondents on power distances and different dimensions prevailing in their current place of employment. The respondent had to rate each statement on a scale of 1-5 in terms of agreement and/or disagreement. The highest concurrence with a statement was rated by 5, and the non-consensual statements by 1.

Twelve respondents agreed—fully or partially—with the statement, “The higher a person is in the hierarchy, the more unattainable (isolated from feedback) he is.” Yet, eight respondents were unsure whether or not they agreed with this statement (Figure 3). A high number of respondents (7) were uncertain about the statement, “Due to his position as a middle manager, he is obliged to cooperate with subordinates and senior management, so he is direct and humane in both directions.” The same number (7) categorically agreed with it. The

Figure 7: Hofstede Power Matrix and Dimensions.

author’s third statement states, “Lower management is the liaison between senior management and employees that results in directness.” The highest number of respondents (8) were unsure how to assess it. Six people fully agreed with the statement, and seven rather agreed. My fourth statement was, “Top executives don’t deal with human support, only lower executives.” Seven respondents were unsure, and another seven rather disagreed with the statement. Two people completely refuted the author’s claim. Three respondents agreed fully, and three – partially. My last statement was, “Due to the power distance resulting from the organizational position, the organizational system becomes task-oriented and office-type.” The highest number of respondents (15) agreed with this statement – 10 fully and five partially. Disagreeing and uncertain were, respectively, five and two of the respondents.

Interpretation of Results and Conclusions

Based on respondents’ views on the author’s three statements related to power distance, it was found that the distances of power in the law enforcement organization differ with respect to the leaders at different levels. Respondents believe that senior executives at the top of the hierarchy are more out of direct reach by personnel. This can be interpreted as a high power distance index, thus reflecting the magnitude of inequality vis-à-vis other members of management. All this presupposes one-sidedness in the issuance of guidance, where the flow of information is one-directional – from the top manager to staff. It should be noted that the number of uncertain respondents showed a relatively high value for this question, but overall, more than half of the respondents answered this question “more or less.” No one disagreed with the statement (rather yes 31.8 %; yes 22.7 %; “more or less” 36.4 %).

Respondents assessed the position of middle managers as a transmission, i.e., a link between senior management and the staff. Its role mediates directness and humanity, thus evaluating the degree of inequality in terms of power distance as small. Although the number of uncertain voters was outstanding here as well, more than half of the respondents agreed partially or fully that the mid-level leader had a cooperative and inequality-sharing role (rather yes 27.3 %; yes 31.8 %; “more or less” 31.8 %). The hypothesis that leadership at the lower levels would be the main pillar of communication and thus the power distance index would be lowest, therefore higher equality among organizational members, was not categorically supported.

Managers at lower levels are in direct contact with staff on a day-to-day basis, which should thus result in directness. Most respondents were uncertain, yet more than half of all respondents agreed partially or fully with the respective statement (yes – 27.3 %; rather yes – 31.8 %).

Regarding power distance, it has been established that the one-way chain of issuing instructions, based on the bureaucratic nature of the law enforcement body, i.e., on the principle of hierarchy and centralized, one-person leadership, has become entrenched over the years (“agree” and “rather agree” combined –54.5 %; 59.1 %, 63.6 %). Nevertheless, the number of uncertain respondents is a good reflection of the fact that some change has started: neither are the results definitive nor could power distances change depending on the hierarchy. This does not obviously mean that staff is not obliged to carry out orders (unless they are illegal) or that it may give an order to a superior. It reflects the fact that managers are also accessible. This is an indication of equality rather than inequality. Commanding care is as important an element of leadership as it is of managing the organization itself. This is a new approach, i.e., in addition to one-person leadership, it can also make the leadership trend an integral part of the law enforcement agency. The issuance of instructions can be carried out in one direction, but it can also take the form of executive guidance and support, in which the staff plays an integral part. Long-term orientation is just as important in this issue, as the beginning of change shows the need for keeping the traditions and development, which presupposes pragmatic problem solving (joint performance of tasks by managers and staff) and adaptation.

On the issue of masculinity and femininity, Hofstede associated masculine traits with performance, success, competition, and perseverance, while feminine traits were associated with tenderness, solidarity, support, and human relationships. The study found that senior executives cannot be categorically considered to be endowed with masculine traits, just as executives at lower levels are not. The number of unsure respondents was the same as those who disagreed, partially or fully, with my statement that, in addition to senior management, only lower managers deal with human issues. All this proves that, regardless of their position in the hierarchy, the top and the lower command, whatever the power distance and inequality, have feminine qualities in support and human relations (rather not – 31.8 %; not – 9.1 %; “more or less” – 31.8 %). Commanding care as one of the tasks of a leader cannot be considered a masculine trait in Hofstede’s theory of dimensions. However, the culture of law enforcement organizations is “leaving no one behind and by himself” in the name of team spirit and solidarity. However, this appears not only at lower management levels but also at the top management level, which can be interpreted as another trend in the emergence of the managerial approach.

On the other hand, respondents clarified that the hierarchy of law enforcement, which corresponds to competition, success, and performance, is the official and task-oriented relationship between direct position and power in the hierarchy and leadership and performance orientation. All this prevails over solidarity, cooperation, and care.

Almost all respondents have a sense of professionalism, which could be interpreted categorically given the substantial number of affirmative respondents (90.9 % yes vs. 9.1 % no). All this reflects that law enforcement work should be interpreted by respondents not only as a job but as a straightforward profession. As a result, respondents are likely to accept all restrictions, such as freedom of movement, expression, assembly, association, and so on. These are restrictions on their constitutional and fundamental human rights, as the Professional Service Act requires. All this symbolizes the limitation of Hofstede’s sixth dimension. In this regard, the organization does not tolerate any leniency; it rejects it. (Although specificity is given by law, it is up to the individual to decide whether to enforce this condition voluntarily. [11]) Of course, all this is supplemented by recommendations in the code of ethics. The results move towards collectivism since by accepting these limitations, the individual can put the service’s interests ahead of his or her individual interests. The ability to work in a team is not a result of teamwork but a necessary component for achieving the purpose and fulfilling the mission of law enforcement agencies as defined by law.

In terms of leadership styles, long- and short-term orientation and collectivism were the most measurable. Slightly more than half of the respondents thought that a democratic leadership style was the most appropriate way to lead a law enforcement agency, while slightly less than half voted for autocratic leadership. The laissez-faire leadership style did not receive a vote (Democratic 59.1 % vs. Autocratic 40.9 %). This is important when it comes to long-term strategy because it requires a general shift from the hierarchical system of centralized leadership and giving and receiving instructions. Respondents believe that the leadership of the organization and its goals can build on collectivism and in line with the hallmarks of a democratic leadership style, rather than being compatible with the authoritarian style endowed by bureaucratic traits. The authoritarian leader does not let decisions slip out of his hands. The democrat believes in teamwork and collective decision-making, which is realized via external and internal cooperation. Thus, managerial communication ranges from one-sidedness to two-sidedness, i.e., the staff is given more space in terms of feedback or instructions’ execution. In addition to individual interests, the group’s interests are also considered.

In light of the research results, the author was able to substantiate his hypothesis only partially. He could only partially prove that the power distance in the law enforcement organization is high. In fact, it is getting smaller. Individualism is being replaced by collectivism, which can also be seen in leadership styles. Constraints remain significant, and uncertainty avoidance is high.

Recommendations

Hofstede carried out his research and the creation of its dimensions at various companies in the private sector. Law enforcement, with its particular characteristics, cannot be uniformly compared to elements of the private sector without consideration of its unique features. At the same time, there is nothing to prevent us from mapping the existence or absence of these dimensions within law enforcement or even proving the emergence of new dimensions, which thus establish a new paradigm within law enforcement opposed to competition. Nor is there any prohibition on using good practices from the private sector, thus encouraging the attainment of the objectives set out in the cardinal laws (for example, the Basic Law or the Police Act.)

Neither the private sector nor law enforcement can avoid the effects of globalization and transformation. New procedures, new methods, and new good practices can enhance the functioning of law enforcement, guarantee the achievement of goals and ensure that individuals feel safe. This requires specific procedures that maximize strengths and opportunities, eliminate threats, and remedy weaknesses. One of the subjects and central elements of this may be the development of a managerial attitude, which in the sense of communicating these partial results of the research leads to a new world, a perspective that seemed unthinkable for law enforcement a hundred years ago.

Given the new research findings, it is worth considering the extent to which the six dimensions set up by Hofstede could improve law enforcement if incorporated into leadership awareness during leadership training. What would happen if collectivism could play a role in addition to success orientation, which is not just about making a profit but rather about satisfying a social goal? Why not invite an executive driven not by his personal goals and interests but by the creation of a collective value – security? Why not give up selfishness to meet the social need for creating security?

This is not a question of one-person, centralized leadership, of hierarchy as a specific feature of law enforcement, but of the emergence of a new trend to guarantee the application of humane and collectivist leadership styles into the system. The research results confirm that we have set off in a direction that predestines the significance of the ideas discussed here and their practical implementation. To sustain and further develop all this, it is necessary not to deviate from the path because it leads us in the right direction, ensuring social purpose—the maintenance of public security and the protection of public order—and respect for collective values.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

Acknowledgment

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Vol. 21, 2022, is supported by the United States government.

About the Author

István Kovács, PhD, has been a member of the professional staff of the Hungarian National Police since 2009. He continued his higher education at the Hungarian Police Academy and then at its successor institution, the University of Public Service, and is currently a student at the Faculty of Law of the Péter Pázmány Catholic University. He spent more than eight years in a senior position in the police organization, and after obtaining his Ph.D. degree, he passed on his theoretical knowledge to the students of the university, armed with the experience of practical life. As an associate professor, he participates in the education of undergraduate and master’s students. In addition, as the scientific secretary of the Doctoral School of Law Enforcement, he also performs organizational tasks in doctoral education. As the chairman of the Student Section of the Hungarian Law Enforcement Society, he is passionate about motivating lifelong learning in his students. E-mail: kovacs.istvan@uni-nke.hu

2307-0919.1014.

20/index.html.

jogszabaly?docid=a1500042.tv.