Behind Blue Lights: Exploring Police Officers’ Resilience after the Terrorist Attack at Brussels Airport on March 22, 2016

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 19, Issue 3, p.77-97 (2020)Keywords:

coping, Organization, police, resilience, resourcesAbstract:

This case study on the terrorist attack at Brussels Airport on March 22, 2016 explores the experiences of police officers concerning (a) their coping strategies after the terrorist attack and (b) the (in)formal workplace social support that affects their resilience. A qualitative, exploratory research method was used to answer the research questions, consisting of a content analysis of the police organization, a participant observation and 31 in-depth interviews with police officers who were on active duty during the terrorist attack. The results of this research show that the interviewed police officers primarily adopt engagement coping strategies after the terrorist attack, of which the most cited one is talking to others, followed by engaging in positive action, behavioral distraction, self-evaluation, positive self-talk and emotional numbing. Second, this study revealed that (in)formal workplace social support plays a significant role to foster police officers’ resilience after a terrorist attack. Informally, getting acknowledged for the efforts made during the terrorist attack and for psychological loss afterwards is crucial in this process. Besides, emotional support from both colleagues and supervisors is identified as essential. However, the ruling ‘macho’ culture within the police organization is perceived as hampering to talk freely about emotions. Formally, respondents place emphasis on a proper debriefing and a well-organized, easily accessible psychological aftercare. This scientific contribution provides insight into the best practices the police organization can apply to promote the resilience and performance of its employees.

Introduction

The terrorist attack at Brussels Airport on March 22, 2016 (22/3), when terrorists committed a suicide bombing, caused 12 deaths and injured nearly 100 people. Police officers (PO) rushed to the scene within minutes, searching for survivors, evacuating victims, guarding the perimeter of the disaster site and eventually seeking for bodies and body parts. A highly traumatic incident such as this can cause severe stress to the involved PO, and can pose threats to their mental health.[1],[2] Nonetheless, research evidence has shown that PO exhibit diverse reactions after potentially traumatic events (PTE). Only a minority develops posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, going from 7 to 19 percent,[3] while most PO demonstrate resilient trajectories, ranging from 76.7 to 88.1 percent.[4],[5],[6] Although most research has focused on the development of pathology, it is of great interest to gain insight into the factors that foster resilience of PO. In this research area scholars mainly emphasize the relation between resilience and personality factors,[7] the access to social support networks,[8],[9] and coping strategies.[10] Moreover, most studies focus on these domains separately, while resilience is a dynamic multi-dimensional construct that is influenced by a wide range of factors such as culture, personality, peer support and the work environment.[11] These findings lead to the identification of several research gaps. First, there is a dearth of literature examining the role of the police organization itself as hampering or fostering the resilience of its employees. Yet, studying this particular research field is of great interest as previous research shows that a socially supportive environment fosters resilience after PTE.[12],[13] Second, mainly quantitative cross-sectional designs are applied to study resilience of PO.[14] However, qualitative research methods may have an added value as they depict perceptions and underlying processes influencing resilience.[15] Finally, research on the resilience of PO is mainly conducted in Anglo-Saxon countries. Insights in the European context are rare, especially when it concerns high-impact incidents such as terrorism.

The present study aims to understand the support processes that potentially promote resilience. A qualitative approach is used to explore and comprehend the experiences of the PO who were on active duty during the terrorist attack at Brussels Airport on 22/3. More specifically, this research is based on two questions: (1) What are the applied coping strategies of PO regarding the terrorist attack of 22/3 and (2) Which formal and informal workplace social support is perceived as affecting police officers’ resilience in the aftermath of 22/3?

Theoretical Considerations

Defining Resilience

Since the concept of resilience has been brought to attention in various academic fields in the past few decades, scholars have attempted to unravel the processes that explain how certain people thrive in the face of adversity while others struggle and develop psychological problems.[16],[17] This shift towards a solution-focused approach centered on positive aims, protective factors and adaptive capacities also occurred in research on the mental health of PO when they experience stressful situations. Several studies provide growing evidence that PO demonstrate resilient behavior in the face of adversity.[18] However, there is no consensus among scholars on how to conceptualize resilience.[19] Moreover, a clear-cut definition of resilience in the research field of PO is still lacking.[20]

Based on the work of Paton, Violanti and Smith [21] and Bogaerts,[22] in this article resilience is defined as “a person’s ability to draw upon individual, inter-relational and organizational resources to cope and bounce back or develop from the confrontation with potentially traumatic events and keep functioning adequately afterwards.”

The Concept of Coping in the Aftermath of PTE

The resilience process is facilitated by the use of coping strategies.[23] Coping can be defined as “a stabilizing factor that can help individuals maintain psychological adaptation during stressful periods; it encompasses cognitive and behavioral efforts to reduce or eliminate stressful conditions and associated emotional distress.”[24] Coping is a complex, dynamic process that depends on the interaction between the person and the environment. This means that the appraisal of stressful situations and coping strategies can change over time and depending on the situation.[25]

There are numerous ways to cope with adversity. In their review, Skinner and co-authors distinguished 400 ways of coping and over 100 ways to categorize coping strategies.[26] The lack of consensus in identifying the core categories of coping among scholars makes it difficult to create a cohesive image of the construct of coping.[27] This research uses the classification of engagement coping and disengagement coping to reveal the coping strategies that PO rely on in the aftermath of 22/3. Engagement coping intends to deal with the stressor or related emotions.[28] These types of coping strategies tend to moderate the psychological harm that can be caused by PTE.[29] Examples of engagement coping strategies that are frequently used by PO are the use of humor,[30] spirituality/ religious coping,[31] acceptance of the situation,[32] and ventilating with peers.[33] However, engagement coping strategies are not always beneficial: for example, cognitive coping strategies such as introspectively reflecting on the incident or self-blame appear to be risk factors for the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms.[34]

Disengagement coping strategies aim at escaping threat or related emotions. They are generally associated with increasing mental health problems as it changes nothing about the threat’s existence and its eventual impact.[35] However, there is growing evidence that they prove to be helpful at some point. In this regard, emotional distancing or psychological numbing can be an adaptive mechanism in high-risk professions.[36],[37] It allows PO to ‘get the job done’ and stay focused.[38] This avoidant behavior can be temporarily functional to reduce early levels of hyperarousal and regain control of yourself and the situation.

However, this notion of ‘taking a break’ is contrary to the persistent effort at defending against negative affect. In the long term these kinds of coping strategies do not contribute to the mental health of PO.[39]

Workplace Social Support as a Coping Resource

While coping strategies emphasize what people do when they deal with PTE, coping resources refer to what is available to facilitate and influence coping responses. Hart and Cooper define coping resources as “any characteristic of the person or the environment that can be used during the coping process.”[40] Individuals with increased access to personal and environmental resources are more likely to apply engagement coping and less likely to rely on disengagement coping strategies.[41] Higher resource levels are related to better psychological outcomes, more active goal-directed behavior and better problem-solving skills in stressful situations.[42]

This research focusses on the organizational resources that PO rely on after 22/3, more specifically workplace social support. Previous research shows that the characteristics of an organization have a distinct impact on how PO experience, interpret and respond to PTE.[43],[44],[45] A substantial amount of research has been conducted on the role of organizational stressors [46] and their relationship with mental health problems of PO. However, relatively little research has been carried out when it comes to the resources provided by the police organization and their effects on PO’ resilience.[47] Nonetheless, unravelling these resources is of great interest as they guide PO’ coping strategies in the aftermath of PTE.

This study emphasizes workplace social support as organizational resource after PTE. Workplace social support can be defined as “interacting with others in such a way as to satisfy one’s basic social needs for affiliation, affect, belonging, identity, security, and approval.”[48] Workplace social support is situated in interaction with colleagues, supervisors and the organization as such. It can be divided into four categories, namely informational, emotional, instrumental and appraisal support.[49] First, informational support can be defined as the advice, guidance or suggestions one gives to another in a stressful period. Second, emotional support involves the provision of caring, empathy, and trust. Third, instrumental support is the provision of tangible aid, goods and services, such as training, education and equipment. Fourth, appraisal support involves communicating or providing information that is relevant to self-evaluation.

Research Method

Study Design

A qualitative, exploratory research method was used to answer the research questions, with a triangulation of several research techniques. First, a content analysis was conducted, consisting in the study of policy documents and reports of meetings. Second, preliminary conversations with eleven key figures from within the organization were administered in order to obtain more insight into the functioning of the organization and the efforts it has made after 22/3. Third, a participant observation of 112 hours was carried out (between October 2017 and December 2017), aiming to achieve insight in the organizational culture and structure and empathizing with the PO to gain trust. Finally, 31 semi-structured in-depth interviews were performed with PO who were on active duty during 22/3. This approach allowed the authors to obtain an in-depth understanding of the opinions and experiences of the PO participating in this research.

Participants and Sampling

The aviation police at Brussels Airport (LPA BruNat) is a part of the Belgian Federal Police and provides the security at the largest airport of Belgium. This police force included 440 employees at the time of the research, of which approximately 200 worked during and in the aftermath of 22/3. There are no exact numbers available of PO who worked on 22/3. Theoretical sampling was applied in order to create as much variation as possible and to obtain rich cases.[50],[51] Four respondents were recruited by sending an e-mail to all members of the police force and fifteen by talking about the research during the participant observation. Furthermore, the researchers relied upon ‘gatekeepers’ to find more PO willing to talk about their experiences of 22/3. This resulted in 16 extra respondents. The sample collected included 24 males and 7 females, varying in rank, ranging from assistant PO, police inspectors, chief-inspectors to commissioners. Ages varied between 27 and 58 years old and years of service went from 4 up to 41 years.

Procedure

Based on the content analysis, participant observation and a literature review, the sensitizing concepts of the topic list were developed to guide the in-depth interviews. However, the flexible and open-ended nature of the interviews allowed the respondents to discuss other topics related to the study. The interviews were conducted between December 2017 and April 2018, of which twenty at the airport and eleven at the respondents’ home or at the researcher’s office. The length of the interviews varied from 49 minutes to 129 minutes.

Data Management and Analysis

All of the interviews were audio taped and transcribed verbatim. Data were organized, coded and analyzed using the qualitative software program NVivo. The coding process was twofold: on the one hand, a deductive approach was used based on the sensitizing concepts of the topic list. On the other hand, new codes were developed inductively, starting from the data itself.[52] Finally, codes were reclustered according to the detected key categories, which yielded the most important research findings.

Ethical Considerations

All respondents signed a consent form that outlined their rights during the research, including the right not to answer questions and the possibility to withdraw from the interview at any time. All identities were kept confidential and any information that could lead to the identification of the respondents was removed from this article. Ethical approval was granted from the Ghent University Ethical Committee and the Belgian Federal Police.

Results

Coping strategies in the aftermath of 22/3

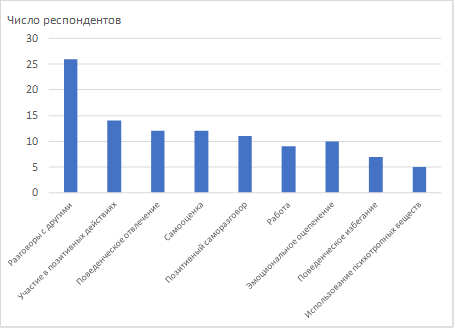

All through the day of 22/3 nearly all respondents switched to automatic pilot, with a high focus on doing their jobs. At that point, there was no room for acknowledging their own emotions. This section focuses on how PO dealt with 22/3 afterwards. Figure 1 summarizes the coping strategies that were addressed across the interviews. In addition, we discuss the effects of 22/3 on the personal and professional lives of the involved PO.

Figure 1: Coping strategies applied after March 22, 2016.

Engagement Coping Strategies

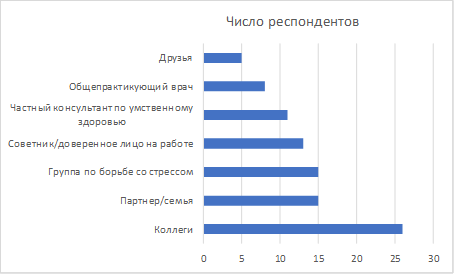

Talking with others, as a means of venting about the incident and/or feelings, was the most cited coping strategy among the respondents (see Figure 2). Support is primarily sought with colleagues. Second, partners are highlighted as being crucial to rely on after 22/3. In the safety of their homes, respondents can show their vulnerability and emotions. On the other hand, some respondents are concerned not to shock or upset their loved ones, and this makes them reluctant to share details of their experiences. Respondents in relationships with another PO most perceived this as valuable because it helped them to feel freed up to talk frankly. Third, some respondents counted on their close friends, mostly to find distraction from negative thoughts. Fourth, several respondents turned to a professional counselor outside work: the general practitioner is perceived as a trusted person who introduces specialized assistance when necessary. Consulting a therapist is another well-used source of support: expressing emotions to a therapist in a neutral setting reduces the concern of risking to damage their career by showing vulnerability. On the other hand, some respondents felt restricted to share their stories, because their therapist did not understand the ‘language’ of the police world well enough. Other difficulties were finding a therapist they connected with or somebody who is qualified enough in the subject of traumatology. Fifth, a substantial number of respondents relied on support organized at the workplace to vent their emotions or frustrations: fifteen respondents depended on the Stress team of the Federal Police,[53] and thirteen PO found support with the psychologist or victim assistant within their department. Finally, five respondents indicated that they tended not to talk to peers or a professional counselor. They described themselves as ‘hardened’ by previous traumatic experiences at work and believed that therapy was not beneficial for them. They preferred to just ‘get on with the job’ or process the incident by themselves.

Figure 2: Sources of social support by talking with others.

The second most cited coping strategy is engaging in positive action, such as addressing shortcomings or problems in the aftermath of 22/3 to the trade union or the staff management. This enabled some respondents to place a positive value on a negative event. Furthermore, writing down experiences and feelings assisted to restructure thoughts and empowered some respondents to take a distance. Additionally, reminiscing about the attack by going back to the crime scene, re-watching videos or fact-checking with peers helped to find closure.

Third, both behavioral distraction and self-evaluation are frequently applied coping strategies. Engaging in relaxing activities such as playing sports, taking a vacation, meditating or going out is helpful to blow off steam and to escape from a spiral of negative thoughts. Focusing on positive activities generates renewed energy. When making a self-evaluation of 22/3, eight respondents struggled with feelings of self-blame and guilt, having the idea that they failed the victims. These negative ideas are diminished by getting acknowledged for their efforts by colleagues, superiors or the victims themselves. On the other hand, four other respondents explicitly declared feeling good about their response to 22/3. They stipulated to have done everything they could within their own potential and give meaning to their actions by concluding they made a positive contribution to the whole.

Fourth, several respondents addressed positive self-talk as an efficient coping strategy. Looking realistically at the situation, reminding themselves things could be worse and reflecting on the good things in life builds acceptance and enabled the respondents to move on with their lives.

Afterwards, I watched the documentary of 9/11. Then I think that was 1000 times worse, and those guys also moved on. (R1)

Finally, continuing to work appeared to be important for nine respondents, especially for those who are single. Staying at home has a distressing effect and provokes negative thinking. Working offered them distraction, created a certain routine and the opportunity to ventilate with peers.

Disengagement Coping Strategies

A regularly adopted disengagement coping strategy is emotional numbing. Several respondents consciously detached from their feelings and avoided thoughts about the magnitude of 22/3 in order to protect themselves against overwhelming emotions. This kind of distancing enabled them to continue with their daily activities. However, in most cases these blocked emotions emerged after the confrontation with certain triggers, going from weeks to several years after 22/3. Those who have not experienced this, were concerned to ‘crash’ sooner or later.

The day after the attack the psychologist came by and I thought “What are you doing here with me? I don’t need this; I’ll get over it myself. By continuing to work this will pass.” But that wasn’t the case. I was able to push these feelings away for several months, but then the lights went out. And I completely crashed. (R28)

Second, several respondents mentioned using behavioral avoidance strategies, such as avoiding any kind of news about 22/3. Moreover, two PO avoided the airport after 22/3 and two others withdrew from social life.

There is little notification of the (ab)use of substances in the aftermath of 22/3. Only one respondent declared starting to drink heavily shortly afterwards as a reaction to strong emotions. Four other respondents mentioned using calming or sleeping medication for a short period of time, but indicated being concerned to become dependent of it.

Effects on Personal and Professional Life

22/3 affected the lives of all respondents, both personally and professionally. Ten respondents explicitly reported that 22/3 affected them more profoundly than other PTE because it took place in their own work environment.

The big difference is that it took place in our own work place. That makes it more confronting. When you go to a murder scene somewhere else, that’s further away from your personal life. Now it was in our own territory. Our own colleagues. A colleague who lost his leg makes it entirely different. (R19)

Nearly all respondents indicated to show posttraumatic stress symptoms after 22/3, such as sleeping problems, physical exhaustion, concentration problems, anxiety and re-experiencing the attack. In most cases, these symptoms disappeared after several weeks.

Most respondents said they were hyper-vigilant at work the first weeks after 22/3, which faded away after a period of time. However, fifteen respondents developed a continuous alertness for terrorism-related signs at the airport, which is experienced as very exhausting and distressing. Furthermore, nine respondents felt unsafe whilst at work and tried to avoid certain places such as the departure hall. The same kind of behavior is reported in private situations: fifteen respondents were more cautious and suspicious in public spaces such as concert halls, cinemas or malls. Furthermore, nine respondents admitted to be frequently insensitive and unkind towards their loved ones at home and stated that there is a clear distinction between their functioning before and after 22/3. For three respondents 22/3 has been a considerable factor for the end of their relationship.

I always say… there is your life, family and job from before the attack, and there is the one after the attack. (R26)

On the other hand, 22/3 established both personal and professional growth: half of the respondents mentioned to appreciate life more. They focus on what truly matters and enjoy the little things in life such as love, laughter, companionship and being in nature. Furthermore, they put things more into perspective, show more empathy and reflect more on their job performance, which gives them an improved sense of control in other critical situations.

Organizational Resources in the Aftermath of the Terrorist Attack

Formal Workplace Social Support

Emotional support. Most respondents were satisfied with the psychological support provided by the organization. Fifteen respondents relied on the Stressteam of the Federal Police, six went to see the psychologist at LPA BruNat and seven respondents turned to the victim assistant of LPA BruNat. The individual contacts with the members of the Stressteam were mainly positive: because of their knowledge of police work, respondents generally had a good connection with them and felt free to talk. Furthermore, it was appreciated that they were available practically immediately after 22/3, easily approachable and that they took the initiative to contact the PO frequently. However, a couple of months later the members of the Stressteam withdrew from LPA BruNat. Several respondents with delayed posttraumatic symptoms experienced a high threshold and felt ashamed to contact the Stressteam themselves. Moreover, speaking up and showing vulnerability was perceived as risky by some respondents because this could be passed to the staff management and influence their career negatively. Furthermore, in addition to individual counselling, the Stressteam organized a debriefing for different teams several days after the attack. For some respondents this intervention came too soon, since they still were in denial and detached from their feelings in order to ‘survive.’ Others experienced this group discussion as threatening because they felt vulnerable to share their emotions in public.

Instrumental support. Across the interviews three themes of instrumental support provided by the organization were discussed, namely the debriefing, administrative support and training/education.

Two months after 22/3, the Federal Directorate of the Aviation Police organized a debriefing for all members of LPA BruNat, which posed several problems according to the respondents. First, not everybody was aware of this event or able to attend it. Second, the respondents who were present recall that the debriefing was merely a monologue for a large group of PO. They had a strong desire for an operational debriefing exclusively with the PO who worked on 22/3. This would create the opportunity for an open dialogue and to solve the main misunderstandings between PO about each one’s contribution on 22/3. Two years later, the new staff management organized a debriefing-moment for the PO who worked on 22/3, explaining administrative procedures and showing the video images of the attack while giving them an opportunity to talk about their experiences. Although it came late, several respondents were grateful for this initiative.

Afterwards you realize that you miss certain parts of that day, and you want to know what exactly happened in the end. (R15)

In addition to the emotional impact, 22/3 brought some administrative and judicial consequences for the involved PO. Twenty respondents declared that they got injured physically or psychologically. Several of them registered for the statute of ‘victim of terrorism’ and/or filed for a civil complaint. These registrations are perceived as important to get acknowledgment and to find closure. The respondents reported that the administrative support by the organization was inadequate. Guidance was lacking and information was given in an unstructured and fragmented way. For this reason, eight respondents did not start or did not go on with the administrative/judicial procedure. The respondents suggest creating a central contact point within the organization for coordinating and following up the files.

You had to figure it out yourself. They did not guide you in the process. No, you had to take the initiative yourself. That’s why I’ve waited so long to go on with it. You don’t know how to get started. (R26)

The procedure is very complicated. That’s why I’ve put it all in the shredder. You can go on forever. (R4)

When making a self-evaluation of 22/3, nearly all respondents consider themselves insufficiently trained to deal with a similar situation. However, they are not convinced whether specific training would guarantee proper actions in extreme situations. The respondents feel a strong need for regular training and exercise in ‘daily’ police work. It enables them to develop their professional skills and perform confidently under difficult circumstances.

During the interviews, most respondents emphasized physical training to be able to cope with adversity. None of the respondents had heard of the existence of mental training and resilience programs. Nevertheless, there was a strong interest to attend this kind of trainings. Despite their positive reaction, four respondents were also skeptical: they believed that the implementation of resilience programs would be hampered by the ruling macho culture within the police force.

I think it would be very useful, but I’ve never heard of it. And I think a lot of colleagues who would be too proud or too tough to be willing to follow such courses. “Come on, don’t be silly, you have to man up, this is our job.” I don’t agree with that. (R8)

Appraisal support. Although appraisal support from the staff management and the police force in general is perceived as indispensable (e.g., by writing a good report or giving a medal of honor), the respondents recall getting insufficient formal recognition for their efforts. Moreover, they had the impression that the staff management was unaware of the impact of 22/3 on their employees. Statements such as “Isn’t the drama over yet? It’s been two years” (R11), or “You’re still not over it after two years? You were not injured, right?” (R18) are perceived as offensive. Not being recognized for their work or psychological loss led to anger, frustration and demotivation with several respondents. In this respect, one respondent mentioned ‘secondary victimization.’

Informal Workplace Social Support

Colleagues

Informational support. Given the perception that administrative support organized by the police force was lacking, most respondents found out themselves how to manage the administrative and judicial procedure and shared this information with their co-workers. Furthermore, PO informed each other with referencing to certain doctors, therapists or lawyers.

Emotional support. As already mentioned above, most respondents sought support from their colleagues after 22/3. Remarkably, they mainly talk about their frustrations regarding 22/3 and less about personal emotions. In this respect, eighteen respondents referred to the ruling ‘macho’ culture at the workplace, where showing signs of vulnerability is perceived as being weak. Consequently, they are cautious to share their thoughts and feelings with their colleagues, which makes it harder to process 22/3. Some respondents revealed that when they did express their emotions, they got laughed at by other colleagues and judged for being weak.

Okay, the macho culture within the police has always been there and always will be. Especially in the aftermath of the attack, I have the impression that you cannot show weakness. This form of ‘social control’ is that strong, that it influences yourself. That you’re afraid to say “I’m having a hard time” or “I’m not sleeping well.” … No, within the police there’s no attention for that, on the contrary. (R29)

On the other hand, thirteen respondents found emotional support with colleagues they connected with on a deeper level and/or who experienced the same adversity. Sharing their emotions in a safe, accepting environment is highly valued and perceived as a crucial factor to deal with 22/3.

Finally, thirteen respondents reported that support was expressed by seeing each other, sending text messages or making phone calls to check if colleagues were alright. This thoughtfulness was highly appreciated.

Appraisal support. Being acknowledged by colleagues for the efforts made during 22/3 seems to be another essential aspect to cope positively with the incident. Getting a ‘pat on the back’ or a simple ‘well done’ gave the respondents a feeling of gratification and increased their self-confidence. On the other hand, several respondents mentioned the insensitivity of some colleagues towards psychosomatic problems after 22/3, especially when complaints took a longer period of time. Reactions such as “aren’t you over it yet?” or the accusation of abusing the health system led to loneliness, frustration and ultimately difficulties to cope with 22/3.

Supervisors

Informational support. Most respondents thought that informational support from supervisors was limited. In this respect, the interviewed chief inspectors and commissioners declared that they tried to support their team members based on their personal expertise. They picked up distress symptoms from colleagues and advised them to see a doctor or therapist. The lack of information on how to assist the team members with administrative or judicial questions frustrated them.

Emotional support. Opinions differ on the extent of emotional support provided by supervisors. Seven respondents declared that their supervisors showed emotional engagement by regularly asking how they were and by emphasizing that they were available for a talk. A supportive supervisor with good leadership qualities is identified as a crucial supportive factor in the aftermath of 22/3. A good leader is described as decisive, understanding, compassionate and correct by the respondents. Supervisors with these qualities enable respondents to feel more confident about their professional skills, especially in crisis situations. Moreover, this kind of leaders endorse a trust climate where team members can be themselves.

On the other hand, thirteen respondents claimed that their supervisor was not considerate about their thoughts and feelings at all. This lack of support generates feelings of frustration and abandonment by the police force.

On March 22 we helped people, and the day you need help yourself, you’re being left in the cold. Until today, two years later, I have been waiting for a phone call by our supervisor from back then to ask me how I am. I haven’t received it yet. (R28)

Six respondents with a supervisory role expressed their strong feelings of responsibility for the well-being of their team members after 22/3. They were concerned when they noticed a co-worker was having a hard time and tried to be available for them. However, three of the supervisors experienced this as burdensome, as they had to cope with their own traumas of 22/3.

At that moment you’re too much occupied with yourself, to cope with it yourself… I had to come to terms with my own emotions at first, before I could pay attention to signals of distress from my own team members. (R26)

Instrumental support. Several respondents pointed out that their direct supervisor granted practical needs after 22/3, such as a change of job content or adjusting work schedules to go and see the doctor. Nevertheless, five respondents complained that their desire to change workplace was ignored by the staff management at the time of 22/3. This led to demotivation and higher rates of absenteeism. However, the current staff management allowed such requests, which was experienced as healing for their trauma.

Appraisal support. Nearly all respondents emphasized the importance of getting acknowledged by their supervisor after 22/3. It enhances their self-confidence and keeps them motivated during hardship. Nevertheless, only a minority of superiors expressed their appreciation for the efforts that were made on 22/3. The respondents declared that this is inherent to the police culture, where performing well is often taken for granted.

Discussion

The aims of this article were (a) to examine the coping strategies of PO after the terrorist attack of 22/3 and (b) to study the (in)formal workplace social support that is perceived as affecting PO’s resilience.

In accordance with the first aim, data analysis revealed that the interviewed PO primarily adopt engagement coping strategies in the aftermath of 22/3, of which the most cited one is talking to others. This is in agreement with findings of previous research that discovered that being able to ventilate and expressing feelings to normalize experiences after PTE is a crucial resource for first responders.[54],[55],[56],[57] In addition to support from colleagues, partners play a crucial role in the coping process of PO. The police organization should make efforts to reinforce and strengthen this resource by creating a partnership with families and organize, e.g., family days or support groups.

Other frequently adopted coping strategies identified in this research are behavioral distraction, engaging in positive action, self-evaluation, positive self-talk and emotional numbing. Concerning the latter strategy, the police organization should be aware of the fact that some PO develop delayed posttraumatic symptoms.

Interestingly, religious faith/spirituality as a coping strategy is hardly mentioned in the Belgian context, which is in contrast with previous research.[58],[59],[60] This also goes for the use of (black) humor.[61] Although humor is acknowledged as a fundamental part of the police culture, in this case it is perceived as inappropriate because of the seriousness of 22/3.

Furthermore, this study discovered that a considerable amount of PO demonstrates posttraumatic growth after 22/3. This finding is consistent with previous research that has found that posttraumatic growth is a relatively common outcome in PO after PTE.[62],[63]

In accordance with the second aim of the study, our findings revealed that workplace social support plays a significant role to foster resilience of PO after PTE. Crucial in the coping process of the involved PO, support at the workplace is being recognized by the police organization for the efforts made on 22/3 and for the psychological loss afterwards. This is important both on the formal level – by the staff management, and on the informal level – by colleagues and supervisors. It establishes feelings of gratification, enhances self-confidence and keeps PO motivated during hardship. However, giving compliments or expressing gratefulness proves to be uncommon in the police culture, where performing well is often taken for granted. Disregarding the impact of 22/3 on the involved PO provokes anger, frustration, feelings of abandonment and demotivation.

In addition, this study demonstrates the importance of informal emotional support at the workplace. Although PO primarily turned to colleagues to vent themselves after the 22/3 attack, they express their frustrations rather than their emotions. In this respect, the ruling ‘macho’ culture is addressed, where discussing fears outspokenly and showing signs of vulnerability could be perceived as being weak and ultimately have a detrimental effect on the reputation of PO. There is a strong need for an open, nonjudgmental atmosphere at the workplace that normalizes sharing emotions and encourages co-workers to be considerate for signs of psychological distress. In this regard, supportive supervisors have an important role to play in endorsing a trust climate where concerns and emotions can be openly discussed.

With regard to formal workplace social support, this study emphasizes the value of a well-organized, easily accessible psychological aftercare for the involved PO. In the case of LPA BruNat, the experiences with the members of the Stressteam were mainly positive. However, although the majority of the respondents connected well with them and felt free to talk in individual counselling sessions, some were suspicious about using this formal resource as it could be a manner to detect ‘weakness’ in PO, which is perceived as harmful for career prospects.

Besides, a proper debriefing is declared as an essential resource to cope with 22/3. This tool helps to restructure the course of 22/3 in order to recollect the memories of some PO and to solve misunderstandings between colleagues. However, mixed opinions were given about the timing of such a debriefing, whether it should be mandatory or not, and who is granted to attend it. Overall, debriefings should be organized in a psychologically safe environment, with room for open dialogue.

Furthermore, several of the involved PO were physically and/or psychologically injured as a consequence of 22/3, which conveyed some administrative and judicial implications. Being recognized as a ‘victim of terror’ by the government or being able to actively take part in the trial is pointed out as an essential resource to find closure with regard to 22/3. PO require instrumental support from the police organization for this matter and recommend a central service for coordination and follow-up of the files. This suggestion is in accordance with the findings of the Parliamentary Research Commission ‘Terrorist attacks,’ which was founded on April 22, 2016 in response to 22/3.

Finally, this study revealed that PO disclaim the importance of physical training to prepare for extreme incidents, as they believe this would not guarantee a proper reaction when it comes to a real incident. However, there is a strong need for training and education in ‘daily’ police work. Since resilience is a learnable, dynamic process that changes in the context of person-environment interactions,[64] police organizations can commit to initiate education and training programs that provide PO with physical and psychological skills that foster resilience.[65]

In conclusion, this study provides insights on the best practices for the police organization to assist its employees in coping with PTE. This leads to a better understanding of how to foster PO’s resilience and job performance. In this respect, organizations should invest in providing the best resources for their personnel by focusing on three levels: (a) the individual PO (e.g., training programs), (b) the organization itself (e.g., restructuring) and (c) the individual-organizational interface (e.g., communication, participation).[66] This triple focus creates a platform for better policies, procedures and a culture that enhances the capacity for resilience.[67]

Limitations and Future Research

This research has several limitations. First, the findings of this qualitative study of a specific case cannot be generalized for the whole police population. Nevertheless, this study provided profound insights in a unique traumatic event that has not been examined yet. Second, although the respondents seemed frank about their experiences, socially desirable answers have to be taken into account in the results. Third, the interviews took place approximately two years after 22/3, which increases the risk for retrospective recall bias. However, this can also be interpreted as a strength given the delayed mental health problems of some PO.

Since resilience is a dynamic process, future research would benefit from longitudinal studies that provide more insights in the evolution of coping strategies during and after PTE. Besides, a mixed-methods approach to examine resilience of PO during their daily operational hassles or the influence of police culture on the application of coping strategies would also be of interest. Moreover, since organizational stressors such as bureaucracy, autonomy, management and communication may be a greater source for stress for PO,[68] investigating ‘job context’ factors related to resilience of PO in general is an interesting avenue for future research.

About the authors

Marleen Easton is Professor and chair of the research group ‘Governing & Policing Security’ (GaPS) at the Department of Public Governance & Management at Ghent University. She has more than twenty years of experience conducting mostly qualitative, empirical research on policing and security related topics that include processes of (de)militarization, community policing, radicalization, police (re)organizations, police culture, citizen participation, innovations in policing and the policing-science nexus. She combines this with an active role as board member of the Belgian Centre for Policing and Security where interaction between researchers and practitioners is stimulated. Her current research focuses on the governance of security in relation to events and flows and on innovations in relation to technology and security. Since 2017 she is adjunct professor at the Griffith Criminology Institute where she is participating in the Evolving Security Initiative and runs the ESI Ghent hub (ESI@GNE) focusing on the governance of security in relation to flows. Since 2014 she is president of the Innovation Centre for Security (IUNGOS) in Belgium. In collaboration with private companies, the public sector and knowledge institutions, IUNGOS is generating innovative projects in relation to technology and security. E-mail: Marleen.Easton@ugent.be(link sends e-mail)

Vanessa Laureys, MSc in Criminology and joined the police-force in 2004. She worked at the local police of Sint-Niklaas as a patrol officer, responding to emergency calls. From 2016 to 2020 she was an academic researcher at the Department of Public Governance & Management at Ghent University, where she studied resilience of first responders in the aftermath critical incidents. In 2020 she returned to her roots as a police officer.